Gen Z Kid Saw Mom Help Elderly Neighbor—7 Years Later It’s Come Full Circle

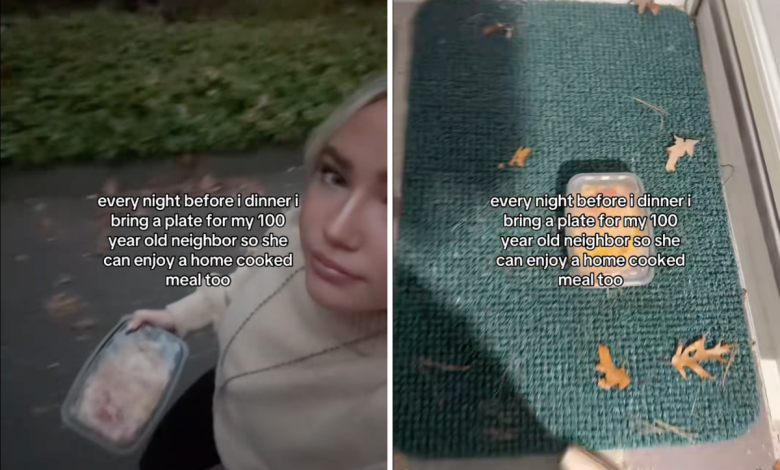

A woman has melted hearts across the internet for the way she supports her elderly neighbor.

Mariel Darling (@mariel_darling), 23, a singer-song writer and New York University master’s student, said she grew up with a community-first mindset passed down from her mother. Her TikTok video about the gesture has since garnered 311,700 likes and 2.2 million views.

Darling explained that she has lived in the same home for 23 years and that growing up in a small Massachusetts community taught her to “truly love thy neighbor.”

“So many people today don’t even know their neighbors, let alone interact with them—even something as simple as sharing a meal or saying hello. I wanted to remind people that a small act of kindness can make a big impact,” Darling told Newsweek.

Around seven years ago, she said her mother helped their elderly neighbor find round-the-clock care so she could remain supported and comfortable. From there, the two families began sharing meals.

As both are of Italian heritage, she said food naturally became their way of connecting and showing love.

She said she never expected the video to go viral. Instead, she simply wanted to share something she and her mother have been doing for years—and that when she is away in New York City, her mother brings the meals over.

Darling explained that they always cook extra as part of their Italian culture and often order additional portions when out to dinner. With the holidays approaching, she said she hoped the video would encourage others to remember that community and togetherness matter just as much as celebration.

According to Darling, the reaction online has been overwhelmingly warm. She said it has touched her to read comments from people who were inspired to start sharing meals or checking in on their own neighbors.

She described the outpouring of support and the stories in the comments as reminders that “humanity [feels] so alive”—and that the holiday spirit feels even more beautiful. While acknowledging that a few negative remarks surfaced, she said the love “always shines through.”

Darling added that, if there is one takeaway, it is to think about the people around you—whether through sharing a meal, offering a wave, or simply smiling—because those small gestures mean more than many realize.

Though her career has brought her to the city, she said the Massachusetts suburbs will always be home, and she returns often to be with family because “family and community are everything.”

In the viral clip, Darling wrote: “Every night before I dinner I bring a plate for my 100 year old neighbor so she can enjoy a home cooked meal too,” overlaying the video with the caption.

TikTok users were quick to respond.

“This is beautiful. You’re a gem,” said Trish.

“You’re a doll, cooking is a love language,” added another user.

“I just know God will continue to bless your beautiful soul,” said Kels.

“Such a beautiful soul for that,” wrote another viewer.

However, Darling also faced criticism from some users who suggested the gesture was performative or questioned whether the Tupperware container was too low for an elderly woman to pick up. She clarified that she posted the act to inspire others and noted that her neighbor has a caregiver who picks up the meal for her.

“Wow these comments are WILD. Such a lovely gesture,” another user commented.

Do you have any viral videos or pictures that you want to share? We want to see the best ones! Send them in to life@newsweek.com and they could appear on our site.