After the battering and bruising in the campaign we witnessed in recent weeks, yesterday’s inauguration of our 10th President came as a welcome respite.

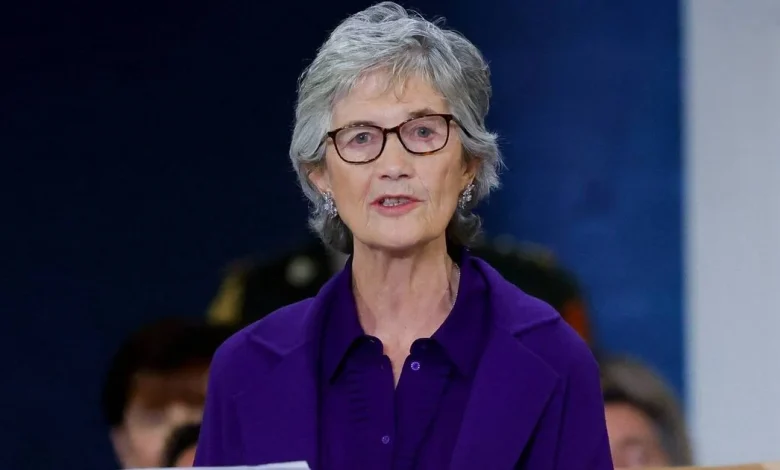

Catherine Connolly was sworn in at St Patrick’s Hall in Dublin, where all our presidents have been inaugurated since 1938. The ceremony, which began with a service of prayer and reflection, was attended by the Taoiseach, the Tánaiste, members of the judiciary, politicians from all parties, as well as former presidents Mary McAleese and Mary Robinson.

This peaceful transfer of power should be acknowledged. As we have seen in other jurisdictions in recent years, the democratic succession of political leaders cannot be taken for granted.

President Connolly’s first speech in office acknowledged the challenges faced by her predecessors, such as the collapse of the Eastern bloc in president Robinson’s time and the Good Friday Agreement that was negotiated while president McAleese was in Áras an Uachtaráin.

The new President pinpointed some of the most pressing concerns of our own time when saying her election victory was a mandate to articulate a vision of Ireland “where everyone is valued and diversity is cherished, where sustainable solutions are urgently implemented, and where a home is a fundamental human right”.

The new President also spoke in Irish and made a strong pledge to use Irish while in office — in fact, to use it as a working language of the Áras. It was a significant statement, given that Ms Connolly’s fluency as Gaeilge was contrasted with the lack of ability in Irish of her opponents in the election, Heather Humphreys and Jim Gavin.

The President’s natural command of Irish comes at a cultural high water mark for Gaeilge, given the popularity of Irish language rappers Kneecap and the success of the film An Cailín Ciúin — and even Cillian Murphy’s “go raibh míle maith agaibh” when winning an Oscar for Oppenheimer.

In that sense, the new President is in tune with the flourishing of the language and its adoption by the younger generation. When President Connolly quoted Pearse yesterday, she struck a chord which will resonate with those Irish speakers: “Tír gan teanga, tír gan anam.”

Erosion of crime deterrence

Yesterday, we learned how many convicted criminals are free to walk our streets under temporary release provisions.

At least one victims’ group has said the numbers revealed show the justice system is weighed in favour of criminals.

Figures released under Freedom of Information legislation to Ireland South MEP Cynthia Ní Mhurchú showed that last June, 558 men and women were on temporary release from Irish prisons last June — but the devil is in the detail.

That figure included 45 people who were listed as having been convicted of attempts or threats to murder, assaults, harassment, and other offences; 20 people convicted of offences against the Government; 12 convicted of robbery, extortion, and hijacking offences; and eight people convicted of weapons offences.

Before weighing up the philosophy behind the concept of temporary release, some fundamental questions must be asked. How can dozens of people convicted of crimes ranging from attempted murder, hijacking, and weapons offences be deemed worthy of temporary release from incarceration? We must acknowledge the overcrowding in our prison systems and the necessity to relieve that overcrowding on occasion, but it beggars belief that demonstrably violent individuals are being given their freedom in this way.

The response has been predictably harsh. Ms Ní Mhurchú said temporary release should only be considered in limited circumstances for non-violent offenders, “not in the widespread way it is being implemented today”.

Joan Deane, of victims’ advocacy group AdVIC, said the figures “underline the core failing of the Irish criminal justice system, which is weighed in favour of the offender”.

The AdVIC view is difficult to contradict given these figures. If there are no real consequences on conviction, even for violent crimes, then there is no deterrent in the criminal justice system. At a time when many citizens are increasingly concerned about safety in our towns and cities, revelations such as these strengthen that sense of unease. A major review of the temporary release scheme to align it with the views expressed by Ms Ní Mhurchú is surely in order.

Goodbye to rugby royalty

Irish sport lost a couple of immortals in the last week — Irish rugby specifically.

Last weekend, Cork native Barry McGann passed away at his home in Greystones, Co Wicklow. At club level, he lined out for Cork Constitution and Lansdowne, collecting 25 caps for Ireland between 1969 and 1976, a time when such honours were far harder to gather.

McGann also played soccer for Ireland at underage level, and he played League of Ireland with Shelbourne.

Another Irish rugby icon also went to his reward last week-end when Mick Lane, Ireland’s oldest surviving Lion, passed away peacefully at his home in Cork City on Sunday. He starred with both Dolphin and UCC, won 17 Irish caps after his international debut in 1947, and toured New Zealand and Australia with the Lions in 1950. He made 11 appearances on the tour, scoring five tries and playing one Test against both Australia and the All Blacks.

To say both men played in a different era of sport is an understatement. One of Lane’s last games was for Dolphin in a Cork Charity Cup final. When opponents UCC equalised, one of the student players fainted with the excitement.

Ar dheis Dé go raibh siad.