A proposal earlier this year sought to sell off public land. In Big Sky Country, Montanans put up a fight.

Montanans earlier this year rallied against a proposal in Congress to sell public lands, perceiving the effort, introduced as part of the “big, beautiful bill,” as an attack on their way of life.

In Montana, the open frontier is valued as an emblem of freedom and possibility. So Montana Rep. Ryan Zinke, who served as secretary of the interior during the first Trump administration, rallied others in Congress to kill the proposal .

“It’s not a Democrat or Republican issue. This is an American issue,” Zinke said. “And once you sell land, you’re not going to get it back.”

Why selling public land was proposed

The federal government owns and manages about 640 million acres of American land, most of it in the West and Alaska. In some states, such as Nevada, the vast majority of the territory is federally owned. As the nation expanded in the 1800s — and as Native Americans were forcefully removed — some land was settled by homesteaders or sold to industrialists, but much fell into federal hands. Today, that land is home to the national parks most of us are familiar with, but also vast tracts set aside for conservation, recreation, plus moneymakers like ranching, mining and logging.

60 Minutes

The Trump administration, including Interior Secretary Doug Burgum, has made it clear that federal lands could be generating more value if there were better management, fewer regulations and more vigorous extraction.

When Utah Sen. Mike Lee went further, proposing the sale of as much as 3 million acres of federally owned land across the West earlier this year, it was the first serious effort of its kind in more than four decades. His proposal did not list specific parcels. But he and some Republican colleagues reasoned that selling land would address America’s housing shortage and also help pay down the nation’s debt.

“The federal government controls more land than it can manage, hurting the growth and prosperity of American families and their communities,” Lee said in a statement to 60 Minutes.

What public land means in Montana

They call Montana “Big Sky Country” but inside the state there’s an unofficial motto: “the last best place.” Hemmed by the Plains and the Pacific Northwest, Montana is a patchwork of prairies and mountains, with rivers running through it; about 30% percent of the state is federally owned.

It’s a sparse state; roughly the same geographic size as California, but with a population roughly the size of Greater Fresno: just north of 1 million. Montanans speak fondly of their neighbors, who might live 50 miles away.

As Montana rancher Bryan Mannix said, this land is powerful, spiritual even.

“Some people find that in church or in other ways. And for me, just being out where your feet are on the ground and actually connecting with this space. And then if you spend enough time in those spaces and on that landscape, it’s like land is kin,” he said.

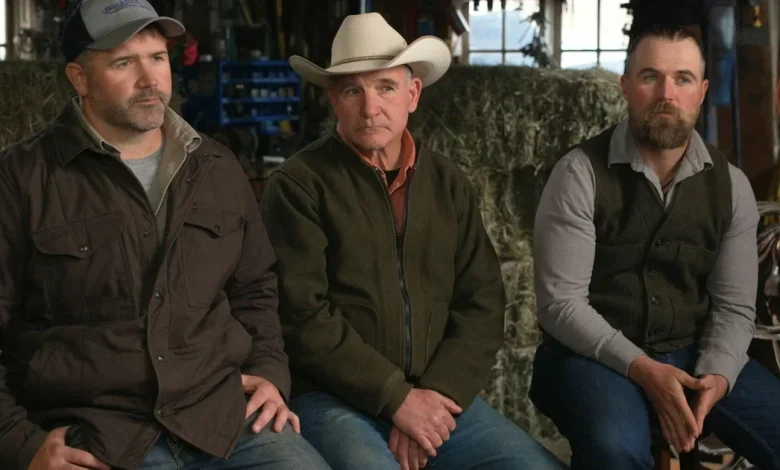

60 Minutes

Mannix raises cattle in western Montana along with his family, including his uncle Dave and cousin Logan. They’ve been on the same plot of land since 1882, ever since their forebears first homesteaded there. The Mannixes consider themselves stewards of the land, which to Bryan Mannix means working it in a way that preserves it for future generations .

“Because this place is going to outlast all of us by a long ways,” he said.

Fighting to preserve public land

In Montana, selling public land was perceived as an attack on a way of life that is already under stress. In recent years, there’s been an influx of wealthy newcomers moving to the state, as U.S. Census data makes clear. Ultra exclusive enclaves like the Yellowstone Club, a private community in Big Sky, Montana, have been expanding.

Home prices in the state have increased nearly 70% in the last five years, according to federal housing data. Private land across the state is being sold and developed; “for sale” signs are everywhere.

The Mannix operation relies on a mix of land, around 55,000 acres all-told: some of it they own, some of it they lease from others, and some of it they pay the federal government to use.

They became worried when the public land sale proposal first surfaced in Washington. While the family could make a living if the public land they use was sold off, the business would be significantly impacted, Logan Mannix said.

Hunting and fishing guide Donna McDonald, sheep rancher John Helle, fly fisherman and river health advocate Chris Edgington and conservationist Emily Cleveland come from across the state and across the political spectrum, but find common cause in a devotion to public lands. They sit on the Ruby Valley Strategic Alliance, one of many local land management groups in Montana and throughout the West

“We all realize the importance of the public land. And once it’s gone, it’s gone forever,” McDonald said.

The Ruby Valley Strategic Alliance spoke out publicly against the sale proposal when it came up this year. They lobbied Montana’s two senators and two congressmen, all Republicans.

Montanans are passionate about public lands, said Rep. Zinke, who grew up in Whitefish, Montana, and now represents the western part of the state in the House.

60 Minutes

“Public lands is not, to me, on a balance sheet,” Zinke said. “Public lands is our inheritance of this great nation. And we’re blessed with it. There is no other country on the face of the planet that has the public land experience that we do.”

Zinke said he’s open to rethinking public land use on a case-by-case basis, within the existing laws, but he does oppose wholesale sell-off.

“You could sell the entirety of the federal estate, it’s not going to get you out of debt,” Zinke said.

Zinke spoke out publicly, calling the federal land sale proposal his “San Juan Hill,” a nod to noted conservationist, former President Teddy Roosevelt: another way of saying “over my dead body.” He worked hard to get the measure killed in the House and Senate even after Montana was afforded a special exemption from any sales.

Still, there’s widespread expectation this issue will come up again in Congress. Montanan Chris Edgington said he sees possible public land sales as a slippery slope.

“If we sell this chunk or that chunk, I mean, where would it end?”

![Best Celebrity Shoes at 2025 LACMA Art + Film Gala [PHOTOS]](https://cdn1.emegypt.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Best-Celebrity-Shoes-at-2025-LACMA-Art-Film-Gala-390x220.webp)