Salman Rushdie: ‘MI6 stopped at least half a dozen attempts to kill me’

Salman Rushdie is back inside the worst day of his life: 12 August 2022, when he was the target of a frenzied knife attack on stage in New York. He wrote about it last year in Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder. Death, he says now, was “very, very close” – closer than he had known then.

“Since I wrote Knife, I’ve been put in touch with one or two of the people who jumped up from the audience to help, and a couple of them were doctors, who I’ve texted with, and one of them said to me that when they came up on stage, they realised I had no pulse. And then they had this idea of lifting my legs up so that the blood would run backwards to the heart…” You may remember this image from the moments after the assault. “So that’s how close it was, that actually my heart had stopped beating. That’s as close as you can get without crossing the frontier.”

Hadi Matar being escorted from the stage as people tend to Salman Rushdie after the knife attack in 2022. (Photo: AP Photo)

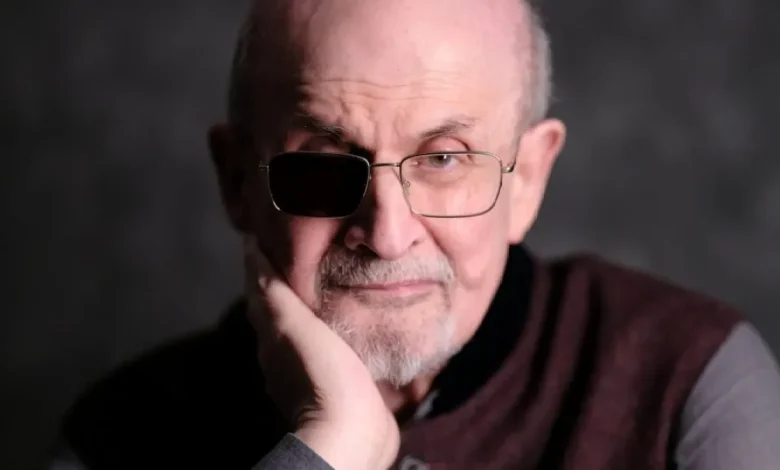

The man in front of me in a bright room is very much alive, undimmed. The scars from the stab wound that cost him his right eye – the blade severed the optical nerve, millimetres from his brain – are concealed by a tinted lens. It gives the 78-year-old a striking visual presence. Since Valentine’s Day 1989, when a fatwa issued by Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini called for his murder, he has been perhaps the most famous living author in the world. Not, he insists, famous “like Rihanna, like Taylor Swift, where you can’t walk down the street” – Rushdie had long since resumed a normal life in New York. And the attack, when it came, seemed like a “blast from the past”.

His 24-year-old assailant, an American-born Shia Muslim, apparently radicalised on a trip to Lebanon, knew almost nothing about him. He had only read a few pages of Rushdie’s fourth book, The Satanic Verses, which had led to the fatwa. It includes a fictional character whom most identify as based on the Prophet Muhammad, but “in my mind, it’s mostly a London novel”, Rushdie says. Many consider it among his best.

Rushdie has just written his 23rd book, The Eleventh Hour, a collection of five stories bursting with ideas, wit and experimentation that feels like a great writer reconnecting with his gift. “It’s about mortality, but I wanted it to feel kind of playful, not ponderous,” he says. That quality in the man who in his 1970s ad-man days wrote the slogans “Naughty but nice” for cream cakes, and “adorabubble, delectabubble, irresistibubble” for Aero bars is never far from the surface. He has the most disarming laugh; it’s almost a titter.

“The first thing I wrote was the ghost story,” he says. He had a character in mind that melded EM Forster (whom he’d met – and played croquet with – while studying History at King’s College, Cambridge in the 1960s) with the mathematician Alan Turing (also a late fellow of King’s). But when Rushdie sat at his desk, he tells me, his prose took an unexpected turn – “I wrote this sentence, which said, ‘When the Honorary Fellow S. M. Arthur woke up in his darkened College bedroom he was dead’. And I thought, ‘What?’”

“Late” is one of three stories in The Eleventh Hour of almost novella length – a new form for Rushdie, whose 1981 breakthrough novel Midnight’s Children (voted the best-ever Booker Prize winner in 2008) was 672 pages long. Yet he notes it’s a form used by some of his favourite writers – Gabriel García Márquez in No One Writes to the Colonel and Kafka in Metamorphosis, both well under 100 pages. One review described The Eleventh Hour as a coda. “I certainly don’t think of it as an ending,” he says. “I’ve noticed that one or two people writing about it said, is this a farewell? No, it’s not. It’s just a book. I certainly hope that whatever comes next is a full-length novel. I have a kind of idea of what it might be, but I don’t think it’s ready to talk about yet.”

He writes differently to how he did in his youth, he adds. “When I was younger, I was a bit wilder. I would write much, much more in a day, but it would require much more rewriting, and some days I would let myself off the hook and not write. Now when I’m writing, I write every day, and I do it like a job. I wake up in the morning, I have a cup of coffee, I go to work. And I write much less in a day than I used to. If I can get a page, I’m very pleased. Sometimes I tell myself 200 words a day. Sometimes I say 300 words a day… [and] I’m working on revision all the time.”

The final part of The Eleventh Hour’s dedication reads “and to Eliza, of course” – referring to his wife, the American poet Rachel Eliza Griffiths, more than three decades his junior. On his second appearance on Desert Island Discs last weekend, Rushdie chose as his song of songs The Isley Brothers’ “For the Love of You”, which Griffiths had entered to at their wedding in 2021, “looking devastating”. Is Salman Rushdie a romantic? “I think probably yes,” he says. “I mean, I must be, given my chequered history.”

Rushdie has been married five times, and has two sons: Zafar, 46, from his first marriage to Clarissa Luard, and Milan, 28, from his third to Elizabeth West. His fourth, to US TV host Padma Lakshmi, ended in 2007. “The truth is, when I was previously divorced, which was a long time ago, around the time of my 60th birthday, I really thought, ‘That’s probably it.’ And I was all right with that. I thought, ‘okay, I have a nice place to live and enough money, and I’m doing work I love, and I have my friends, and my children’.” He now has two grandchildren, as well. “So I was completely reconciled to that. Then I got taken by surprise.”

Salman Rushdie and his wife Rachel Eliza Griffiths (Photo: Roy Rochlin/Getty Images for Authors Guild Foundation)

I mention a notorious Sunday Times interview from 2010, which painted him as a literary playboy and party animal in the years after his divorce from Lakshmi. It was, he says, “the rudest interview anybody’s ever done with me. It just was a hit piece. And I thought, ‘Really? You asked me to bring my children along to be photographed at the zoo, and then you write an attack piece.’ I thought, ‘Fuck off.’

“If you ask people who actually know me, I’m not like that. I mean, I much prefer seeing people in very small groups or like, one person, because then you actually talk to people and you find out what’s really happening in people’s lives. I don’t like big, glamorous things. I’ve had to go to my share of them, but I’m always very happy to leave.”

It was a deliberate policy to show up at events and be photographed, he says, so that people around him could see that he was not scared – and perhaps relax around him. He recalls once when his agent Andrew Wylie took him out to dinner – “and in the restaurant was a very well-known painter, who came over to say hello to Andrew, and then he looked at me, and he said, ‘Should we be frightened and leave the restaurant?’ And I said, ‘I’m having dinner. You can do what you like.’ But it made me think, if that’s the thought bubble in people, then I have to do something to puncture that.”

In the early days, before he moved to New York, his own fear had been imminent and real; on hearing the news of the fatwa, he wrote once, he’d thought: “I’m a dead man.” He’d begun calculating how many days he had left to live, numbering it in single digits. In his memoir, Joseph Anton (an alias he began using after the fatwa), he described leaving his home in Islington that day for the writer Bruce Chatwin’s memorial service and being told by the police that he must not return.

Salman Rushdie holding a copy of The Satanic Verses in 1991. One month later, Ayatollah Khomeini placed a fatwa on him, claiming the book was blasphemous against Islam (Photo: David Levenson/Getty Images)

Paying for his protection detail was hotly disputed in the press – “I remember a lot of people saying I didn’t deserve it,” he says. The police weren’t saying that, he adds. “They were very clear about what they were doing and why they were doing it. I had a few meetings in the James Bond building on the river, with very senior spies… They were all absolutely clear they were not going to allow a foreign power to execute a British citizen in his own country… From what I was told, there were at least half a dozen serious attempts, which as the MI6 people said, were frustrated.”

A similar debate rages around the protection of Prince Harry, “I think the Royal family has always had a very high analysis of threat,” he notes. “I don’t want to get into the Harry thing, but I think the Royal family would do well to patch up their grievances.”

He maintains a belief in free speech as a core principle, even though he recognises it is also the banner under which would-be authoritarians march. “Plenty of people misuse the argument. And those are the people who are actually book banners and so on.” He mentions a report that lists 23,000 books currently subject to bans in the US. “One of the things the books have in common is that they express versions of America which the current authority in America is trying to erase. So if they’re books about gay people, if they’re books about trans people, certainly if they’re books about black people, then those are the books that are being challenged and censored. And that’s obviously a project, and fortunately, there is a backlash against it.”

Your next read

Of course, Britain is now witnessing the rise of its own right wing nationalist party under Nigel Farage. Rushdie, who was born in Mumbai – he still calls it Bombay – was educated at a British public school, Rugby, in Warwickshire, where he experienced explicit racism from his fellow pupils, who scrawled, “Wogs go home” on the walls of his study cubicle. “It’s so long ago that I don’t care,” he says now, putting it down to how “young boys find ways of being nasty to each other”. Would he say the same of the accusations of racism and antisemitism at school that have swirled around Farage recently? “In the case of Nigel Farage, I think I would probably not brush it off,” he snorts.

He’s glad that he’s not starting out as a writer now, because of his sense of “peer group pressure about what’s acceptable and not acceptable” to write. “I mean, 23 books down the road, I kind of don’t care what pressures there are. I’m just doing what I do.”

As for the threat of AI, he says, “I just shut it out of my consciousness. I have a friend who set chat GPT the task of writing 300 words of me, and it was unbelievably bad. I mean, nobody who’d ever read my work would mistake it for something that I would write. So I thought, ‘Well, that’s comforting.’ But on the other hand, I also know that this stuff learns very fast, so maybe next week, it would be better. I do think it’s incapable of originality”.

“The word novel,” he adds, “contains the idea of the new.”

The Eleventh Hour is published by Penguin (£16.99)