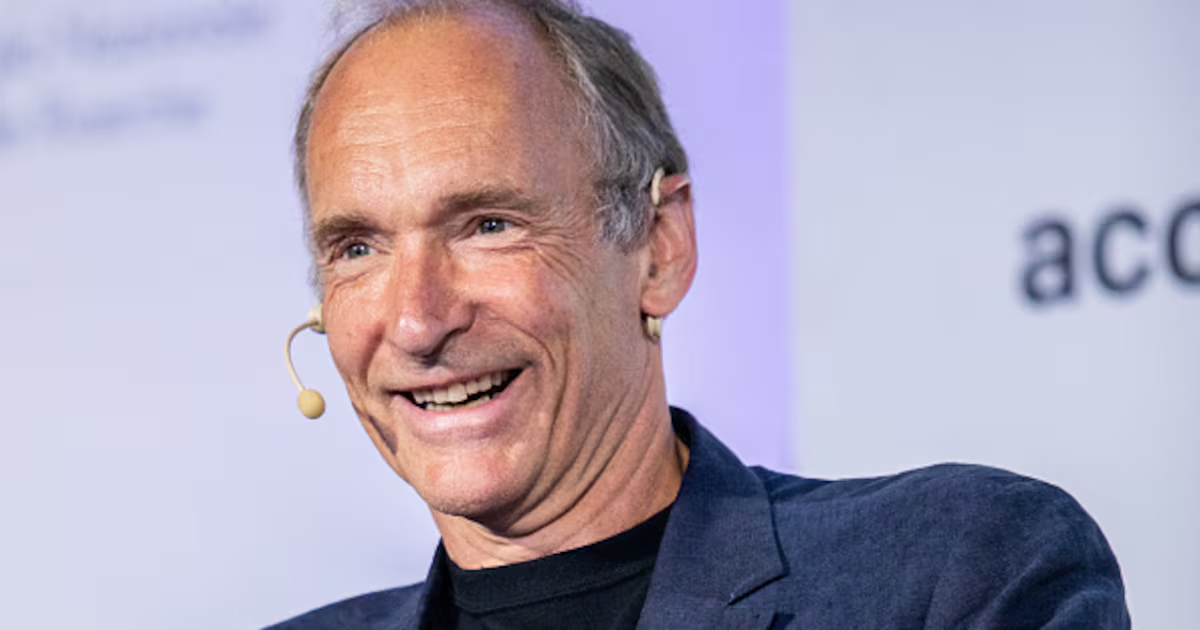

TIM BERNERS-LEE | The man who invented the world wide web

I was thirty-four years old when I first presented the idea for the World Wide Web. At the time, I was working in Switzerland as a programmer at a particle accelerator. No one was asking for the web, and almost no one expected anything to come from it. I had never been to Silicon Valley, had no connection to venture capital, and was far from computer science research centres like Stanford University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

I had no track record as an inventor, held no patents, had never started a business, had never managed a team of people, and had published only a couple of research papers. My job was at CERN (originally the European Council for Nuclear Research, now the European Organization for Nuclear Research), the international high-energy physics lab in Geneva, Switzerland, the largest and most complex laboratory of its kind ever built.

CERN’s mission was to discover the ultimate nature of matter — what is it? Where does it come from? To do this, CERN accelerated beams of subatomic particles on a gigantic racetrack, faster and faster, then smashed them into each other to see what happened. I helped write the code that allowed all the many computers and devices there to communicate with each other.

Working at CERN was pretty good fun. There were projects and people from all over, and lots of different sorts of computers — from mainframes in the computer centre, to workstations in the control centres, to microprocessors in the tunnel around the accelerator, which was located in a 27km-long circle, 300m underground. To keep track of all these complex systems, I needed — in fact, they needed — a powerful information system that would bridge those projects, those different types of computer systems, those teams, those people and those ideas. (Did they know they needed it? Nope.)

This is for Everyone by Tim Berners-Lee, published by Pan Macmillan (Pan Macmillan)

I spent a long time thinking about how to do this. Then, around 1988, I was struck by the idea of combining two pre-existing computer technologies into a single platform. The first technology was the internet, which is a protocol for connecting computers; you’ve probably heard of it. The second technology was hypertext, which takes an ordinary document — like a technical manual, or a diary entry — and brings it to life by adding “links”. My idea was that these hypertext links could provide a simple way for users to navigate the internet.

This kind of decentralized structure could have a network effect on creativity: new trends, possibilities and products would emerge as millions of people started linking, sharing and following across the planet. If you could put anything on it, then, after a while, it would have everything on it. Because my idea could connect so many people, systems and countries, I called it the World Wide Web. But when I described this vision to people, most of them seemed to regard me as a little eccentric.

CERN’s assignment was to discover the origins of matter, not sponsor experimental networking technology. Still, I relentlessly petitioned my bosses at CERN to fund the World Wide Web. I took every opportunity to discuss it, pitching it in meetings, sketching it out on a whiteboard for anyone who showed the slightest interest, or even finding ways to raise it in informal settings. My friend Meryl Dalitz recalls me drawing the concept of the web in the snow with a ski pole during what was meant to be a peaceful day out on the slopes. I don’t think Meryl could see what I saw. What she could see was my passion. I still have that passion more than 30 years later. Actually, I think I have more passion now than I did then. The diagram I drew in the snow melted, but my idea —the World Wide Web — is now used by more than half the world. It’s one of the most successful inventions of all time. Just as I’d hoped, it has enabled a flourishing of human creativity and self-expression, and I think we’re only beginning. In fact, I believe that the only limit to what can be created on the web is our own human imaginations.

— Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the world wide web.

In this book, I want to tell you the story of how the web came to be. How I finally secured some time to work on it from CERN, and how I built the first web page, the first web browser and the first web server, all on a single computer in a small room on the second floor of the computing and networking building. How I met my early collaborators online, and how that small, single server expanded into a small network of servers, then to a large network of servers, and then a really large network of servers, moving so fast that by the end of a decade we’d taken over the globe.

I want to tell you the story of how the web evolved. I left CERN in 1994 and relocated to MIT, where for the next 28 years I led a consortium that oversaw the advancement of the web from a primitive collection of networking tools into the powerful suite of technologies that now power much of our online life.

Today, the web is everywhere, on everything, powering most of the applications you use and delivering much of the content to your mobile phone. It delivers streams of media to your television, and serves as the front end for a trillion dollars’ worth of global transactions every day. This didn’t just happen — it took an enormous amount of collaborative work for the web to evolve in this way. That work continues to this day, powering new technologies like videoconferencing, augmented reality and, of course, artificial intelligence (AI), whose impact is only just starting to be understood.

AI breakthroughs are coming so rapidly that it’s difficult to keep pace. From a technical perspective, what’s happening is that software designed to mimic the human brain is “evolving” on giant computers, some big enough to fill a warehouse and some surprisingly small. These AIs need data to train, and much of that data (especially for systems like ChatGPT) is sourced from the web. The resulting systems are so powerful they seem like magic. In the near future, our lives will be transformed by AI “agents” that will interact with the web and take actions to achieve specific goals. You might ask an agent to book you a vacation, or file your taxes; you might use it to tutor your children, or order your groceries. The agent connects to the web to complete these tasks, and in doing so, it constantly improves along the way.

As you’ll see in this book, I’ve been envisioning these types of web agents since the mid-1990s — I just couldn’t predict what form they would take! The AI wave is one of our biggest opportunities yet, and promises to deliver a great deal of value for humankind. But experience suggests we also have to be careful; this technology is so powerful that it threatens dystopian outcomes. Sadly, we’ve already seen how things might go wrong.

Over the past few decades, I’ve fought to keep the web transparent, opensource and freely accessible. Unfortunately, in recent years, along with all the creativity, empowerment and collaboration that I love on the web, a small, but significant part of it — the addictive forms of social media — have multiplied into something misleading, toxic and habit-forming. That’s pretty far from my vision. But because this small part of the web is so addictive, people spend a lot of time on it, and as a result most web traffic is now concentrated in a handful of large platforms that harvest your private data and share it with commercial brokers or even repressive governments. That’s pretty far from my vision, too. Worse, authoritarian governments now use the web to spread disinformation and surveil their own citizens, and that’s as far from my vision as can be. While we use and celebrate the good on the web, we also have to address the bad.

In the age of AI, these threats are more urgent than ever before. To ensure the web agents serve people — not corporate profits, not governments, not themselves, but people — it’s critical that we develop systems today that put the human first. In the early days of the web, I put my design tools in the hands of individuals, not administrators or corporations primarily motivated by profit. This was one of the best decisions I ever made. Today, we have to build tools and systems that empower individuals once again.

Fortunately, there are ways to leapfrog the web to a place where it is much better for humanity. When users have greater control over all their data, they can better resist the forces that are degrading their experience, and they can seek out new tools that can improve their lives. In my own work, alongside dedicated researchers at MIT, I’ve developed a system called the Social Linked Data protocol, or SoLiD for short. It permits users to take control over all the data in their lives and put that data together to achieve new results. It returns the web to its roots, giving creators new collaborative tools, while passing power back to users. As AI agents develop, they might even use SoLiD to create trusted platforms for delivering remarkable new services. “Trust” is the key word there — in the world I envision, your relationship to AI agents will carry the same level of privilege and confidentiality that you’d expect from communications with a lawyer or a doctor.

When I was asked to transmit a live message to hundreds of millions of viewers at the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympics, I wrote: “This Is For Everyone”. Now, in the age of AI, I believe that to be true more than ever. We can restore the web as a tool for collaboration, creativity and compassion across cultural borders. We can fix the internet, and the next person to build web tools can push the boundaries of self-expression and deserve our trust. I don’t know who that individual is, and I can’t predict where they’ll come from. What I do know is that that passion is out there, and that if we dedicate our minds to it, we can take the web back.

It’s not too late.

- This is an extract from This is for Everyone by Tim Berners-Lee, published by Pan Macmillan.