The last voyage: remembering the Edmund Fitzgerald 50 years on

It has been 50 years since one of North America’s most infamous maritime disasters—the sinking of the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald. Yet, questions remain unanswered and interest in its story continues to grow

Humankind versus Nature, a theme for this non-fiction storyline.

There’s a land acknowledgement at the beginning and end of the song. You know the lyrics.

About two weeks ago, I was standing beside the now-shined iconic ship’s bell, and some visitors at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum at Whitefish Point, Michigan.

One onlooker remarked, “They still don’t know what happened to the Edmund Fitzgerald that night.”

And there it is, some of the continued unknowns about the tragedy on Nov. 10, 1975, that took the lives of 29 sailors.

There’s more to know. Especially when you find a diver/videographer who has been to the Edmund Fitzgerald and discovered the first body. He’s now a Captain of a fish tug, one of the first boats on the scene on November 11, and he was awarded a commendation for his efforts. And then how an Edmund Fitzgerald life ring ended up on the Slate Islands, approximately 250 km northwest of the tragedy.

Read on, it has been half a century.

When you ask AI about famous ship losses, inevitably, the Titanic and S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald come to the top of the short list. It’s because of the Gordon Lightfoot song; the lyrics remain stuck in our heads.

Fifty years since the “Fitz” or the once known “Queen of the Great Lakes” sank 540 feet to the bottom of the “big lake” about 7 km off of Coppermine Point, north of Sault Ste. Marie, in Canadian waters.

So, where does one go to make a physical connection? This story is a primer with new sidebar stories not so well known, involving some luck.

Background

There’s a lot of information on the Edmund Fitzgerald.

Named after the President and Chairman of the Board of Northwestern Mutual, Fitzgerald was launched on June 8, 1958, at River Rouge, Michigan. Northwestern Mutual placed her under permanent charter to the Columbia Transportation Division of Oglebay Norton Company, Cleveland, Ohio. At 729 feet (222 m) and 13,632 gross tons, she was the largest ship on the Great Lakes for thirteen years, until 1971.

She became known as the “Queen of the Great Lakes” and the “Big Fitz.”

The Fitzgerald’s normal course during her productive life took her between Silver Bay, Minnesota, where she loaded taconite, to steel mills on the lower lakes in the Detroit and Toledo area. She was usually empty on her return trip to Silver Bay. On November 9, 1975, Fitzgerald was to transport a load of taconite from Superior, Wisconsin, to Zug Island, Detroit, Michigan.

The final voyage of the Edmund Fitzgerald began on November 9, 1975, at the Burlington Northern Railroad Dock No.1, Superior, Wisconsin. Captain Ernest M. McSorley had loaded her with 26,116 long tons of taconite pellets, made of processed iron ore, heated and rolled into marble-size balls. Departing Superior about 2:30 p.m., she was soon joined by the Arthur M. Anderson, which had departed Two Harbors, Minnesota, under Captain Bernie Cooper. The two ships were in radio contact. Fitzgerald, being the faster, took the lead, with the distance between the vessels ranging from 10 to 15 miles.

Aware of a building November storm entering the Great Lakes from the Great Plains, Captain McSorley and Captain Cooper agreed to take the northerly course across Lake Superior, where they would be protected by highlands on the Canadian shore. This took them between Isle Royale and the Keweenaw Peninsula. They would later make a turn to the southeast to eventually reach the shelter of Whitefish Point.

Weather conditions continued to deteriorate. Gale warnings were issued at 7 p.m. on November 9, upgraded to storm warnings early in the morning of November 10. Conditions were bad, with winds gusting to 50 knots and seas 12 to 16 feet…

The ship eventually sank in Canadian (Ontario) waters in the early evening of that day at about 7:10 p.m.

It was determined that two tsunami-like waves called the “twin sisters” hit both boats, but the Edmund Fitzgerald lies in two pieces at the bottom of the lake. What happened is the storyline of about 15 books and many documentaries.

Where to Go

Valley Camp

With the current situation between Canada and the US, there was some hesitancy to cross over the bridge. But as always, things fall into place beyond nicely, and the day trip was so worth it.

It was dark when we crossed Sault Ste. Marie International Bridge on October 25.

With Brian Emblin from Timmins, we found out the floating Museum Ship, Valley Camp, was closed for the season. Darn. We went down to the east end of Sault, Michigan, for an early morning photo anyway. I could just report what’s within.

Serendipity ensued.

Walking around the deserted parking lot at 8 a.m., a pickup truck rolled up. Soon enough, as luck would have it, we met Paul Sabourin, curator and tour guide, as we found out, formerly from Sturgeon Falls, Ontario, he had worked for the Ontario government (Culture and Recreation) for thirty years and married an American. One of those small world things.

The next thing you know, we are headed to the archives, where the original blueprint drawings of the Edmund Fitzgerald are housed, and then, towards the hold of the museum ship.

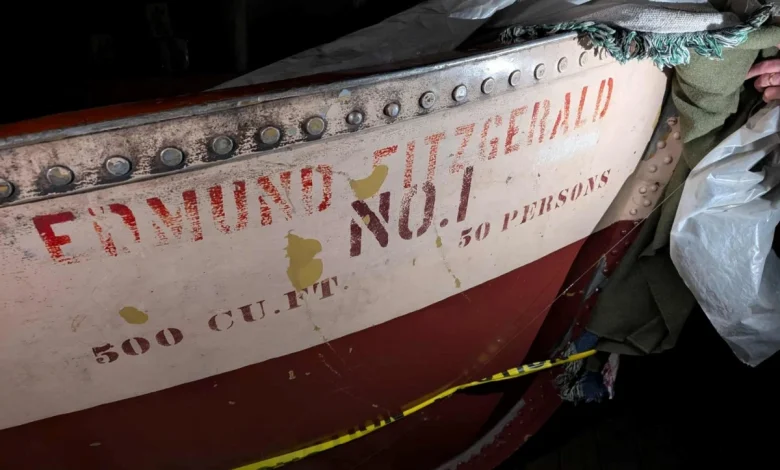

Not everyone knows the museum has two battered lifeboats from the Edmund Fitzgerald, for all visitors to see, in an eerie display at the bottom of the ship.

The museum was getting ready for an on-board community Halloween fundraiser, and scary things were everywhere.

Torn away during the sinking, these lifeboats are two of the very few major artifacts recovered after the tragic demise. The exhibit also features an hour-long presentation about the events that occurred on November 10, 1975, which caused the tragic loss of one of the Great Lakes’ largest freighters. And a great deal about Captain Bernie Cooper of the Anderson, the freighter trailing the Fitz in the storm.

The presence of the Fitzgerald lifeboats display gets around largely by word of mouth, said Paul. The most asked question is about how the Edmund Fitzgerald sank. “I tell them I don’t know, there’s many theories.”

Wrapped in protective plastic, with no studio lights, other than our phones, he pulls back the crinkled wrap to expose Fitzgerald lifeboat Number 1. It was found ripped in half, floating upside down and recovered from Lake Superior on Nov. 11, 1975, by a vessel searching for survivors. They are metal boats, and you can feel the storm when looking at the damage they sustained.

Around the corner is Fitzgerald lifeboat Number 2 was found at Batchawana Bay in one piece, but dented, with a large hole in its left side and its front ripped like paper from damage inflicted by the ferocious waves of Nov. 10, 1975. Paul then went on his way to conduct a tour for a small ship.

I touched them both.

The diver

It is not every day you get to speak to someone who has been there.

I found Ric Mixter through the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum visit. He is also a member of the museum board of directors.

He dove to the Edmund Fitzgerald in 1994, and he is the author of Tattletale Sounds – The Edmund Fitzgerald Investigations.

Edmund Fitzgerald followers recognize Ric Mixter as a shipwreck researcher- diving over 100 shipwrecks in the Great Lakes, including the Edmund Fitzgerald. He has produced over 30 programs for PBS and the Outdoor Channel, and appeared as a shipwreck expert on National Geographic Explorer and the History and Discovery Channels.

Ric is highly respected by his peers, awarded with the 2009 Award for Historic Interpretation by the Association for Great Lakes Maritime History, and the Great Lakes Shipwreck Preservation Society’s 2022 C. Patrick Labadie Special Acknowledgement Award for his thirty years of contributions to shipwreck history.

This book is the compilation of hundreds of interviews from the welders working on the Edmund Fitzgerald in 1958, family members of the sailors, to the regular ship’s cook who was on leave and not on board that day on November 10.

“My original PBS program has plenty of material if you need it,” he said.

He continues to be busy with engagements, as interest in the Edmund Fitzgerald does not wane.

“I’ll have 20 talks between now and December (across) three states and a lot of miles (Duluth is the farthest). November 10, I’m at a round table at the National Museum of the Great Lakes on the Fitz topic. My friends at Whitefish Point will be ringing the bell there in a public and private event just for the families of the lost sailors.” He has rung the bell as well.

“Will I continue to investigate? Not so much. I’ve done four videos, a CD-ROM, a four-hour podcast and a 300-page book on the Fitz. If an opportunity comes to scan or dive the wreck, I will certainly offer my expertise. But I have 5,000 other shipwreck stories to tell, and about 800 more to find in just Michigan waters alone!”

What happened to the ship, I asked him. What’s your theory?

“Decades of neglect on a ship that had issues in heavy weather. The various captains pushed the ship into big storms, and the keel came loose as a result. This was repaired, but they hit other big storms in 1972 and five gales in the spring and fall of ’75 that caused more damage.

“The cook told me the engineer warned the captain of the keel issue, and Captain McSorely’s answer was that it just had to hold together a few more weeks until he retired. The engineer, Mate, wheelman, and Captain were all planning on leaving the ship that winter for good.”

And then…

“I think the damage to the vents and leaking from the hatches (I saw personally that they weren’t all clamped down) caused the ship to be more susceptible to the towering waves reported by the Anderson. That wave jumped over the ship and crushed the Anderson’s lifeboat before speeding ahead towards the Fitz.

“Lower in the water, the big wave pushed the hatches underwater and crushed in hatches one and six. Hatch covers two and three exploded away from the air pressure as the ship disintegrated its midsection on the surface before the stern broke loose and flipped upside down. It skidded over the largest pile of ore that I saw during my visit.”

He will be on the Back Roads Bill podcast on November 12, where he describes the dive to the wreck in fascinating detail, and he discovers one of the sailors’ bodies.

A novel firsthand account.

Theory

Frederick Stonehouse has authored over thirty books on maritime history, including the most recent offering: The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald – 50th Anniversary.

His book was at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum, and I had to find this expert.

He has studied the Fitzgerald mystery since the day she dove for the bottom of Lake Superior. While there are no provable answers, his conclusions have evolved as more information gradually became available. The university researcher has put forth every plausible theory and its trail of evidence in such a manner that lets readers come up with their own.

He has compiled four theories, but the preferred is “the Fitzgerald breaks up on the surface, including the failure of the two forward hatches.”

“The flooding ballast tanks cause a starboard list and forward pitch, causing a rising stern and midsection.“ He said a great deal of stress is created, and the ship breaks in two with the coming of the two enormous waves blowing in the two forward hatches, causing flooding. “At the same time, there is structural failure due to the catastrophic torque.”

After fifty years, he said, “Why does it remain so fascinating? It certainly isn’t due to any heroic actions. While we will never know the actions of the crew in their last moments, there was no time to be a hero.”

There will always be fascination with the Edmund Fitzgerald character.

“It has transitioned from fact into legend,” Stonehouse said.

He was asked what he will be thinking about this coming Monday.

“I’m going to be thinking about a couple of things, including the fact that we have not had another shipwreck on Lake Superior or any of the Great Lakes since the loss of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

“I will also be remembering that to the Great Lakes maritime community. The Edmund Fitzgerald was just yesterday. Not viewed as history as much as a current event. This has resulted in an operational feeling of being more careful with the weather and their ships as opposed to what might have been true 50 years ago.”

While I was at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum, I purchased both books. And then walked out to the windy observation deck among the sand dunes and pea grass. I looked out at the rising waves and envisioned what had happened.

Someone who really knows

He’s probably one of the only living witnesses to the Edmund Fitzgerald aftermath.

Some of the only intact artifacts are found at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum at Whitefish Point, Michigan. There’s the Edmund Fitzgerald’s bell encased for all to see, and rung each November 10. Watch the Edmund Fitzgerald video in the theatre for the underwater footage.

But beside the bell is a transparent display of intact objects from the lifeboats found on shore on the Canadian shoreline and floating in a direct line from the site of the sinking.

There’s a plaque: Donated by the James D. MacDonald family, Mamainse Harbour. I had to find this family. The harbour is just south of Mica Bay, and I know that scenic drive along Hwy. 17 to Wawa, oh so well.

Some people know the fury of Lake Superior and have spent a lifetime plying its waters. Captain James MacDonald is one of those people.

I eventually found him. Captain MacDonald is now 94 years of age and has lived at Mamainse Harbour, north of the Soo, near Coppermine Point for sixty years. He has been on the lake since 1949.

He was one of the first people on the water at the scene of the tragedy in his fish tug, early on November 11. Because of the size of his boat, he was able to do an extensive search of the immediate area.

Fifty years ago, James D. MacDonald felt the fury of the November 10 storm; it was like yesterday, and he took me to the night of the sinking and what followed.

“There are two small islands leading into the harbour that act as a buffer. That night, the surge of water was above the second hydro pole.”

He estimates the waves were about thirty feet. The maritime radio is always on, and he heard the chatter of Captain McSorley of the Edmund Fitzgerald and Captain Bernie Cooper of the trailing freighter, Anderson.

He said the Fitzgerald’s sinking was so quick that no radio message was given, though she had been in frequent visual and radio contact with the steamer Arthur M. Anderson. The Fitzgerald disappeared in a furious snow squall and then from radar.

Captain McSorley of the Fitz had indicated he was having difficulty and was taking on water. She was listing to port and had two of three ballast pumps working. She had lost her radar, and damage was noted to the ballast tank vent pipes. McSorley was overheard on the radio saying, “Don’t allow nobody (sic) on deck,” and that it was the worst storm he had ever seen.

“We responded,” MacDonald said. “It wasn’t until 7 a.m. that we could get out of the harbour and head for the sinking location off Coppermine Point. The only boats in the area were the Anderson (the trailing freighter that heroically came about and looked for survivors, and the William Clay Ford freighter headed upwind) and the Ford.

“They’re big boats, and our fish tug could maneuver quite easily as the winds subsided. You could see a direct line of debris from the sinking location to Coppermine Point. We went back and forth and looked for survivors.”

By 3 p.m. on November 11, the lake was flat.

Over the next two days, they scoured the coastline and found two damaged lifeboats, the two rubberized life rafts, oars, life rings and jackets. Anything that floated. Much of it was turned into the OPP as the investigation with the US Coast Guard got underway. Fixed-wing aircraft were deployed.

There were some items retrieved from the lifeboats we found on shore.

“Our family kept them until my wife got tired of dusting them.” They ended up at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum.

Captain MacDonald has rung the bell at the annual Nov. 10 ceremonies and was asked to speak there this year.

In 1976, he received a US Coast Guard commendation for his search and rescue efforts under post-storm conditions.

What will the captain be thinking as he does every year?

“I think about the men on board and the respect one must have for Lake Superior.” He knows. And I found myself even closer to the Edmund Fitzgerald.

Lyric changes

The lyrics to the song remain stuck in our heads.

The Canadian singer and songwriter recorded The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald and released it on his 1976 album Summertime Dream. The single hit No. 1 in Canada and reached No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart in the United States.

The song, nominated for two Grammy Awards, would go on to become one of Lightfoot’s biggest hits, topped only by his 1974 song, Sundown.

And not so well known to many, Lightfoot changed the lyrics when he performed the song live, out of respect for family members.

Ric Mixter explained some things about revisions to the song.

Though Lightfoot’s lyrics tell a true story, there are some errors or creative liberties in it.

“The Edmund Fitzgerald, which departed Superior, Wisconsin, was headed for Detroit, not Cleveland, as the song goes,” Mixter explains. “The historic Mariners’ Church of Detroit is dubbed The Maritime Sailors’ Cathedral in the song.”

After a parishioner objected to him referring to Mariners’ Church as “a musty old hall,” Lightfoot began singing “a rustic old hall.”

The original lyrics refer to a hatchway caving in shortly before the disaster. But in 2010, an investigation for the National Geographic Channel’s TV show Dive Detectives suggested rogue waves broke the ship in half.

Lightfoot soon revised the lyrics from: “At 7 p.m. a main hatchway caved in, he said, ‘Fellas, it’s been good to know ya.'” To: “At 7 p.m., it grew dark; it was then he said, ‘Fellas, it’s been good to know ya.'”

“That brought relief to the mother and daughter of crew members in charge of manning the hatches.”

Life ring discovery

Another fascinating find was a life ring from the ship. How did an Edmund Fitzgerald life ring find its way NNW 250 km to the Slate Islands in the opposite direction?

I first saw this Edmund Fitzgerald life ring at Neys Provincial Park, west of Marathon, about thirty years ago; it was just hanging on the wall. This past year, I returned to see the Edmund Fitzgerald artifact. It is now encased within protective Plexiglas.

Sheri Bryson was born and raised and lives in Terrace Bay and is the granddaughter of a lighthouse keeper on the Slate Islands, about 13 km off the shoreline.

“While my grandfather, Jack Bryson, was making his rounds around the Sunday Harbour on a spring morning in May of 1976, he came upon the Edmund Fitzgerald life ring on the northwest shoreline of Sunday Harbour.”

The ring was slightly damaged and covered in heavy oil.

“The name EDMUND FITZGERALD was very legible. For a couple of years after it was found, it was stored in the old original light keepers’ house in Sunday Harbour. Then it ended up in safe storage in the basement of Jack’s son, Jim’s, house in Terrace Bay. It remained safe in keeping there until Jack decided what he wanted to do with it.”

“It was pretty neat living in a house that stored the ring. I remember being at one point too young to understand what was in my basement. But it sure gave me the creeps with it being such a bright orange and all the black tar. Once old enough to understand what it was, it was a unique thing to be able to excitedly talk about the find.”

In the early 90’s, he decided he would donate it to nearby Neys Provincial Park to have it encased safely on display for many to see.

“Especially all his grandchildren, whom Jack and his wife, Flora, would bring to Neys every summer to camp for a few days,” she added. “Once donated to Neys, it remained in the back office of the Neys museum in safekeeping until the case and display for it were built.

“I believe that this took quite a few years, as I do remember for a few years after it was donated, every time we went to Neys, we would have to ask to see ‘our grandfather’s ring’ and the staff would bring us to the room they were storing it in to see. My guess is late 90’s the display was finally built.”

She said, “Life as a light keeper’s granddaughter was full of many, many happy and memorable moments. The Slate Islands was basically our summer home growing up.”

Other finds

A rubberized life raft at the National Museum of the Great Lakes, Toledo, Ohio, which was recovered. Take a virtual tour and see the life raft

Here, they have one of two life rafts found by Captain MacDonald of Mamainse Harbour; one is on display. The curator also contacted Bowling Green State University which holds the museum’s photography archives. They sent along some historic Edmund Fitzgerald photos.

We also came back to see a Great Lakes Canadian freighter, the Algoma Conveyor, a self-unloading bulk carrier (2019), enter (2:45 p.m.) and exit Soo Locks Park on Portage Avenue.

You can imagine the Edmund Fitzgerald doing the same.

There’s elevated multi-level open-air and behind-the-glass viewing areas enabling you to see the big boats crawl through at idling speed. You get the feel of shipping on the Great Lakes.

This picturesque park and information center offer visitors to the Sault an opportunity to experience the engineering marvel that is the Soo Locks. Numerous displays inside the Center chronicle the construction and the people who made the locks possible. A thirty-minute movie provides a historical perspective on the need for and use of this maritime wonder.

On the main street parallel with the locks are many tourism shops with names like Fudge du Locke, Lockview Motel and the Long Ships Restaurant. It looks and feels like a tourist town. If you have time, go up the Tower of History, a 210-foot observation tower that offers panoramic views of the Soo Locks, St. Marys River and the Canadian shore.

Back across the bridge, we stopped at the Sault Ste. Marie Museum. There is a new Edmund Fitzgerald exhibit at the museum, including some memorabilia on loan from Algoma University.

We had a great tour of the red sandstone building, learning that its construction dates back to 1904-06 and it was built from material dredged from the process of building the canal.

Museum Coordinator Nicole Curry said, “The Edmund Fitzgerald 50th Anniversary Exhibit will run from Friday, November 7 to Tuesday, November 18, 2025.

“From Algoma University, we have received various videos that we will be digitizing. We also received a model of the ship and, most importantly, some taconite pellets to show what she was carrying.”

We will also have a video that presents the history, the storm, the wreck and searches and finally the theories and mysteries surrounding her. We’ve just launched a podcast episode that showcases what will be included in the video. Although this exhibit is small because we don’t have a lot of artifacts, we hope that the other information we provide will help people to reflect upon this anniversary and hopefully learn something new.

There is also an Edmund Fitzgerald diorama at the Wisconsin Maritime Heritage Center in Manitowoc.

There are many locations to see displays, and now the natural one.

Lookout trail

One way to make an experiential connection to the Edmund Fitzgerald and the lake that took her is to take a short hike to an expansive vista. Maybe this is the best of the links.

It’s a favourite because, after seeing all of the above, you begin to understand the big waters of Lake Superior itself, called Gichigami (or Gitche Gumee/Kitchi Gami), which literally translates to “great sea” or “large body of water.”

On the Canadian side, north of Sault Ste. Marie and just beyond the main campground of Pancake Bay Provincial Park is the Lookout Trail.

A beautiful hardwood walk through towering maple trees leads you to a steel staircase leading to a panoramic view of Lake Superior, the horizon line leads you to the resting position of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

There’s information about the tragedy and a pointer on the sign to guide your eyes to the horizon where the Edmund Fitzgerald went down.

A clearly marked trailhead sign with route information and a map marks the start of the trail. The hike to the lookout and back is around 7 km and takes 2-3 hours. Longer side routes are available, taking you to Pancake Falls or Tower Lakes.

The Lookout Trail is particularly scenic during the fall colour season. See the map for all of the interpretative locations (see the shortcut for the Lookout Trail) as you sing along with the 5:58 song by Gordon Lightfoot.

The Mystery lives on

Surveyed by the U.S. Coast Guard in 1976, the wreckage consisted of an upright bow section, approximately 275 feet long and an inverted stern section, about 253 feet long, and a debris field comprised of the rest of the hull in between. Both sections lie within 170 feet of each other.

A U.S. Coast Guard report on August 2, 1977, cited faulty hatch covers, lack of water-tight cargo hold bulkheads and damage caused by an undetermined source as causes of the sinking. It has not changed since its initial 1977 despite subsequent private dives and competing theories. The Coast Guard maintains that the most probable cause was the loss of buoyancy and stability due to massive flooding of the cargo hold through ineffective hatch closures.

The National Transportation Safety Board unanimously voted on March 23, 1978, to reject the U.S. Coast Guard’s official report supporting the theory of faulty hatches. Later, the board revised its verdict and reached a majority vote to agree that the sinking was caused by taking on water through one or more hatch covers damaged by the impact of heavy seas over her deck.

This is contrary to the Lake Carriers Association’s contention that her foundering was caused by flooding through the bottom and ballast tank damage resulting from bottoming on the Six Fathom Shoal between Caribou and Michipicoten Islands.

The story of the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald is a half-century of intrigue with many theories.

“Superior, they said, never gives up her dead. When the gales of November come early…”