Sweden’s pension disaster sparks urgent warning over ‘danger’ in Rachel Reeves’s plans

Sweden’s big push into green energy is starting to unravel, creating serious problems for those pension savers with money invested

The country had been putting large amounts of retirement savings into clean-technology companies – but two of the biggest names have now run into major trouble.

Northvolt, the electric vehicle battery company once seen as Europe’s leading green hope, filed for bankruptcy protection in November. It had been held up as a symbol of Europe’s environmental ambitions.

Stegra, Sweden’s high-profile “green steel” company, is now facing an £858million funding gap. Harald Mix, the billionaire who helped set up both Northvolt and Stegra, has stepped down as chairman of Stegra’s board.

The losses are now affecting major pension funds. State pension fund AP2 had invested £117.7million in Northvolt before its collapse. It also holds £46.8million in Stegra, plus a further £15.6million exposure through its investment in Al Gore’s Just Climate fund.

AMF Pension, which is jointly owned by Swedish employers and trade unions, reportedly has 1.9billion kronor at risk.

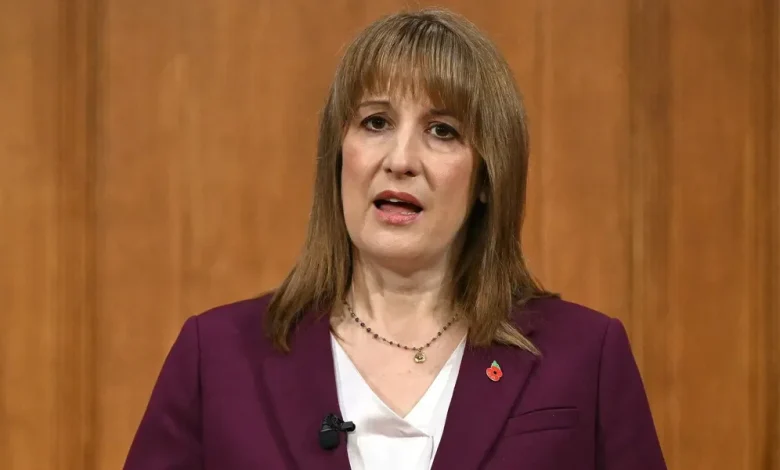

Chancellor Rachel Reeves is taking a very similar path to Sweden’s failed experiment with her Sterling 20 programme. The plan, launched with Britain’s biggest pension schemes last month, aims to channel retirement savings into UK infrastructure and artificial intelligence projects.

Through the Mansion House Accord, the Chancellor secured voluntary promises from pension providers to invest at least five per cent of their assets in UK private markets by 2030. She has not ruled out making these targets mandatory.

This approach echoes Sweden’s earlier push under former Social Democrat prime minister Stefan Löfven, who led a coalition with the Greens and promised a “new green industrial revolution” on the scale of the transformation 250 years ago.

Unlike the UK, Swedish state pension contributions go directly into government-run funds. These funds were early adopters of large-scale low-carbon investments and embraced what they called a “high risk, high reward” strategy long before the Paris Agreement.

Swedish state pension contributions go directly into government-run funds

| Getty

Oscar Sjöstedt, economic spokesman for the populist Sweden Democrats who now hold the balance of power in parliament, expressed fury at the funds’ involvement. “It’s so clear that they just wanted to fool around with the pension funds to propagate their own party policies with no regard to pensioners’ futures,” he said, criticising the previous left-wing coalition.

Magnus Henrekson, economics professor at Stockholm’s Research Institute of Industrial Economics, explained: “It meant the businessmen involved had all the upsides while the downside was socialised.”

He noted that whilst current retirees receive defined benefits, inflation-linked increases aren’t assured.

Rikard Eriksson, economic geography professor at Umeå University, highlighted additional taxpayer exposure: “The Riksgalden [Sweden’s national debt office] has also guaranteed substantial amounts. So on top of the pension fund exposure, it will be the state or the taxpayers who will be reimbursing the company if it fails.”

Tom Gosling, director of LSE’s sustainable finance initiative, warned that Sweden’s experience “shows the dangers” of the Chancellor’s plans. “In a world of high budget deficits and scarcity of public capital, governments are increasingly keen to influence where pensions invest,” he stated.

LATEST DEVELOPMENTS:

Chancellor Rachel Reeves is taking a very similar path to Sweden’s failed experiment with her Sterling 20 programme

| REUTERS

He cautioned: “You can see the clear risks of it with UK pension funds being encouraged to invest in private markets at exactly the time when private market evaluations look stretched.”

Mr Gosling emphasised that pension schemes must resist having “their arms twisted by governments” and avoid overexposure to single-country projects.

The Swedish investments were based on assumptions about aggressive decarbonisation policies that failed to materialise. European Union green subsidies couldn’t match Chinese support for new industries.

When electric vehicle demand weakened last year, European firms like Northvolt couldn’t compete. Meanwhile, Donald Trump’s administration has reversed America’s decarbonisation push, with major investors abandoning climate coalitions.

Hilary Salt, a retired pensions actuary, argued: “If British companies offered the best returns, you absolutely wouldn’t need to mandate pensions schemes to invest in them.”

Retirement funds face huge losses after being exposed to high-risk green projects

| GETTY

She warned: “When pension schemes take investment decisions, it can definitely affect people’s long term income and retirement.”

Jon Greer from wealth management firm Quilter highlighted capacity concerns: “Large funds require substantial, reliable projects to generate returns yet the market may not offer enough viable opportunities, particularly in infrastructure.”

He cautioned that excessive capital pursuing limited projects could force funds “toward riskier or less impactful investments.”

A Treasury spokesman defended the approach: “Pension funds have committed to private market investment targets voluntarily due to the potentially higher returns and security for savers through diversified asset holdings that they offer and scale-up businesses have welcomed these reforms.”

The spokesman claimed the reforms would “unlock over £25bn for the UK economy.”