Volcano Erupts After Lying Dormant for 12,000 Years, Sending Scientists Scrambling

November 24, 2025

2 min read

Volcano Erupts After Lying Dormant for 12,000 Years, Sending Scientists Scrambling

The Hayli Gubbi volcano, long thought to be dormant, sent ash nine miles into the sky in an eruption on Sunday

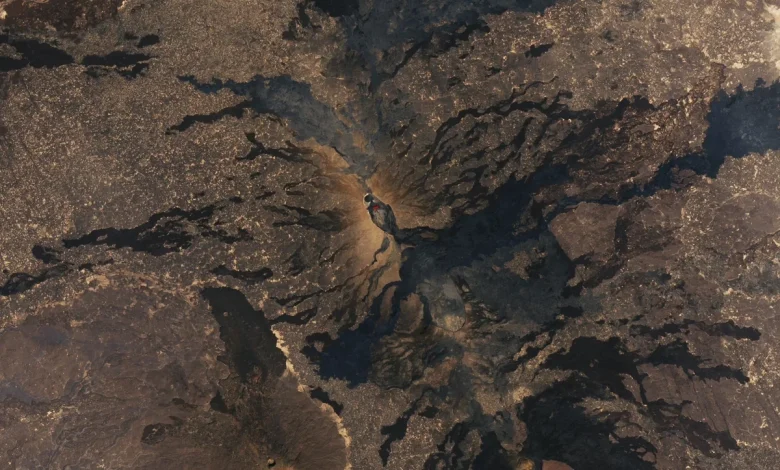

This image shows Ethiopia’s Afar Depression, where Hayli Gubbi and Erta Ale, Ethiopia’s most active volcano, are located.

A long-quiet volcano in Ethiopia spewed ash nine miles into the sky on Sunday, marking the first known major eruption from this volcano for more than 12,000 years.

Under-studied and situated in Ethiopia’s arid, rural northeast, volcano Hayli Gubbi’s towering ash column may be a clue to other, undetected eruptions in that period, says Juliet Biggs, an earth scientist at the University of Bristol in England.

“I would be really surprised if [more than 12,000 years ago] really is the last eruption date,” Biggs says. While there have been no confirmed eruptions in that time span, satellite images hint that the volcano may have recently burped out lava, she says.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Either way, this eruption is highly unusual. Hayli Gubbi is a shield volcano, like Hawaii’s Mauna Loa. These volcanoes are known for oozing lava flows, not expelling giant columns of ash.

“To see a big eruption column, like a big umbrella cloud, is really rare in this area,” Biggs says.

Hayli Gubbi sits in the East African Rift Zone, a region where the African and Arabian plates are pulling apart at a rate of about 0.4 to 0.6 inches a year, says Arianna Soldati, a volcanologist at North Carolina State University. If the two plates keep moving apart, then eventually the Arabian Sea and rift valley will become a new ocean.

As the Earth’s crust pulls apart, it stretches and thins, and hot rocks rise up from the mantle, melting into magma toward the surface.

“So long as there are still the conditions for magma to form, a volcano can still have an eruption even if it hasn’t had one in 1,000 years, 10,000 years,” Soldati says.

Researchers had some idea an eruption at Hayli Gubbi was possible, Biggs says. In July another active volcano nearby called Erta Ale erupted in a shower of ash. At the same time, satellite data revealed ground movement showing that an intrusion of magma from Erta Ale had pushed more than 18 miles below the surface, under Hayli Gubbi and beyond. Biggs and her collaborators had also recorded white puffy clouds at its summit, and the ground at the volcano had risen a few centimeters.

Sunday’s eruption, which poses little danger to people given its remote location, has kicked off a scientific scramble. Derek Keir, an earth scientist at the University of Southampton in England, happened to be in Ethiopia when the volcano blew; on Monday he collected samples of the new ash. These will help reveal what kind of magma caused the eruption, Biggs says. Lava flows from the volcano could also reveal if Hayli Gubbi truly was quiet for 12,000 years.

“It really just shows how understudied this region is,” Biggs says.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.