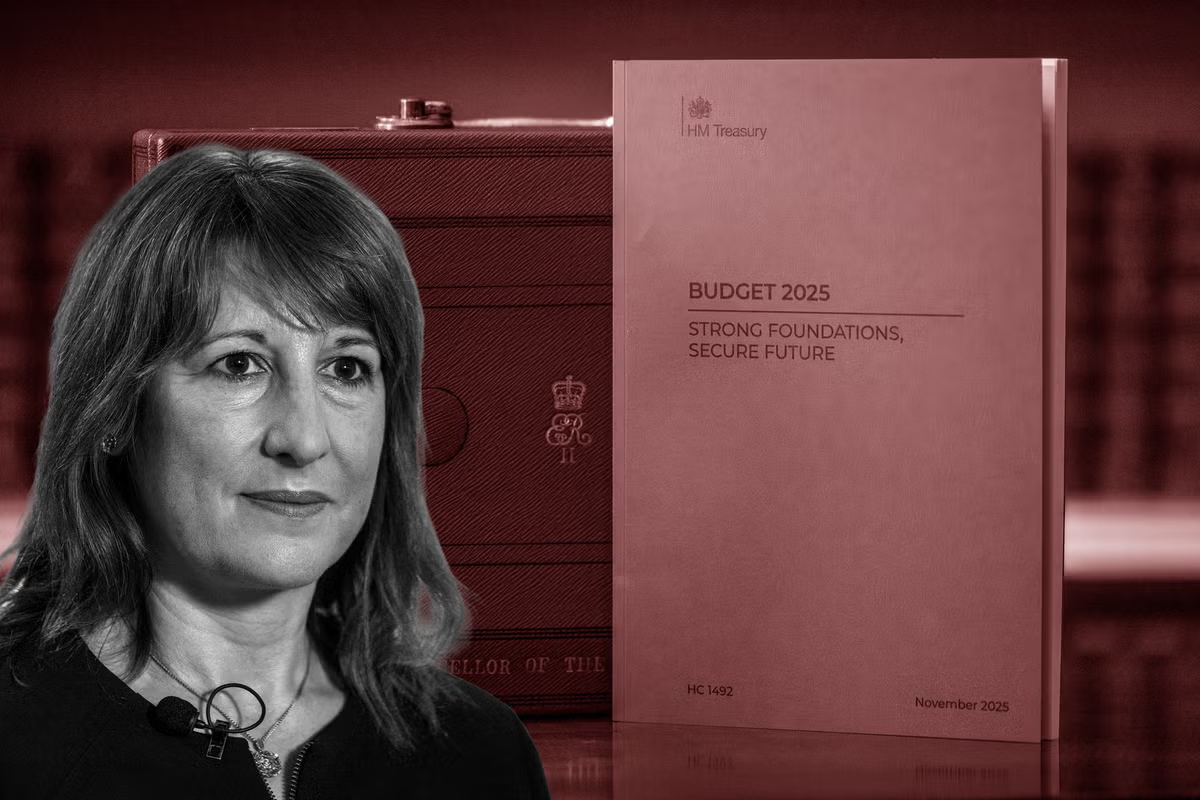

Leaks and lateness have made this Budget the most hated in history – and it’s not even here yet

The pound – a proxy for how the world views the UK economy – surprisingly edged higher against the dollar on the eve of the Budget, despite reports that traders have been betting against it, and amid the fear sown by the atrociously leaky and tumultuous run-up.

We know that chancellor Rachel Reeves’ “make-or-break” event will be unpleasant. But just how bad could it get? Will the fiscal pain be enough to satisfy the bond markets, on which the UK relies to service its vast debt? How much damage will tax rises do to a shaky economy? And how much damage have the leaks already done?

This isn’t, of course, the first leaky Budget. Nearly all chancellors leak something, despite the pious but deeply disingenuous statements one hears from the Treasury about not wanting to pre-judge what the occupant of No 11 will do – often, they’re leaked on purpose, as the bean-counters test potential policies in the press to see how the public will react.

Take 2021. A Sky News analysis found that 15 parts of Rishi Sunak’s post-Covid Budget had found their way into the media, ranging from an increase in “skills spending” to a boost for transport to a rise in the minimum wage.

House of Commons speaker Lindsay Hoyle got very cross, as he often does. He delivered a stern lecture to the government’s miscreant ministers, who pretended to be contrite but weren’t. And with the obvious exception of Hoyle’s raised blood pressure, what harm was done?

Sometimes leaks can be a very good thing, if the reaction steers the government of the day away from a bad or dangerous course. You could certainly make the case that the mini-budget of 2022, the work of Liz Truss and her chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, wasn’t leaky enough.

The string of unfunded tax cuts Kwarteng announced, designed to give the economy a sugar-rush – the last thing it needed at a time of double-figure inflation – caught the markets and everyone else on the hop. The result: a near-economic meltdown. Bond investors fell over each other in a race for the exit. Those who remained demanded a huge increase in yield – the interest rate they were paid – to hang tight. It became known as Britain’s “idiot premium”. Mortgage rates shot up in anticipation of much higher interest rates and several big pension funds flirted with collapse, prompting a humiliating volte-face.

Could a leak or two have headed off the crisis? Might this have allowed Truss to at least outlast the Daily Star’s infamous lettuce?

Gordon Brown didn’t leak his plans to stick to his predecessor Ken Clarke’s tough spending plans prior to his first budget. He made it a promise of the 1997 election campaign. However, there was considerable scepticism over whether he would keep it, partly because there had been considerable scepticism over whether Clarke would have kept it.

Months of speculation over the Budget has fostered the perception that the government is essentially rudderless (Kirsty O’Connor/Treasury)

Brown proved as good as his word. This established credibility with the markets that Labour had previously lacked, and is noticeably struggling for now. The biggest surprise he sprang was to grant independence to the Bank of England over interest-rate policy (rates had previously been set by the chancellor in consultation with the Bank). There was nothing about this in Labour’s manifesto and it proved controversial, with the left in particular. However, it may have been the best decision he took.

What has been startling, and shocking, about the current edition is not the leaks themselves but the chaotic way in which they have been handled. An insider once told me that the problem with the current government is that “they just keep throwing things against the wall in the hope that something will stick and connect with the public”. The trouble is that it is not just the public that matters in this case. It is also the markets and a business community that has fallen out of love with Labour faster than Henry VIII after one of his marriages.

Perhaps the worst example of the pre-Budget dance was when it was reported that Reeves planned to become the first chancellor since Denis Healey to hike income tax, in direct violation of Labour’s election manifesto promise not to do that. This would have proved an efficient and effective way of helping to plug the hole in the public finances, conservatively put at £20bn, although some estimates have gone as high as £40bn. But after floating the idea, the chancellor backtracked on political, if not economic, grounds.

Despite what transport secretary Heidi Alexander claimed during the weekend broadcast round, the amateur hour at the Treasury has spread fear and uncertainty like a winter-cold virus, hurting the economy in the process. It’s a cliché that the markets and the business community hate the latter, but it also happens to be true.

The late date of the Budget has only added to the sense of chaos, allowing dark speculation to spread like wildfire and fostering the perception that the government is essentially rudderless.

The natural response to this among investors is to steer clear, while businesses put their plans on hold and assume a defensive posture, seeking to preserve cash reserves and margins, focusing on firing rather than hiring. Surprise, surprise, the unemployment rate has risen. Alexander was quite wrong. Right there is evidence that the leaks have damaged the economy.

How badly? It may be that some of what’s been put out there is part of the “softening-up” process, traditionally undertaken by governments when they have a problem with the numbers, as was the case last time around. And, of course, the economy could recover from the damage Reeves has wrought.

Here’s the problem: the movers and shakers in industry and commerce, in money managers’ offices and on the City’s trading floors, have all been watching. It will take some time for their faith to be restored. I’m not convinced the current government has the wherewithal to do it at all. That is a serious problem – given the growth that Reeves wants and needs if this country’s deep-seated problems are to be addressed.