How the Inquirer and Daily News covered the 1990s mafia power struggle seen in Netflix’s ‘Mob War’

More than 30 years ago, Philadelphia was the battleground in a brutal mob war as a group of young mafia upstarts challenged the rule of the established La Cosa Nostra leadership.

Known as the Young Turks, that group consisted mostly of younger men who were the sons, brothers, and nephews of former crime family members who were dead or in prison, and was purportedly led by Joseph “Skinny Joey” Merlino and Michael “Mikey Chang” Ciancaglini. They believed that mob boss John Stanfa, a Sicilian immigrant who preferred to keep a low profile, was an outsider who was not fit to lead. Instead, their bloodlines and connections gave them the right to rule their hometown neighborhoods.

Now, a new docuseries from Netflix, Mob War: Philadelphia vs. The Mafia, examines that conflict, complete with interviews from the law enforcement agents and former mobsters who were there, vintage 1990s Philly TV news footage, and the perspective of a hitman-turned-informant who made headlines. The goal, said director Raïssa Botterman, is to show the human element behind the violence.

“They’ve committed crimes, but they’re still humans, and understanding who they were and having their versions of events” is important, she said. “Whether it’s fighting against crime or it’s committing crimes, [we’re] trying to get a more holistic picture of what’s going on.”

Notably missing from the series is Merlino, who Botterman said declined to participate. Merlino has long denied having been behind a faction of the city’s mob and has never been convicted of mob-related violence.

Likewise, Merlino declined through a representative to comment about Mob Wars.

Throughout the ’90s, mob violence regularly dominated Inquirer and Daily News headlines, and resulted in several high-profile deaths and criminal trials, and a new mob leader in the city.

Here is how we covered it:

The war begins

By most accounts, the first strike in the brewing mob war happened in January 1992 with the killing of Felix “Tom Mix” Bocchino, a Stanfa loyalist, on the 1200 block of Mifflin Street. Bocchino, 73, was shot four times in his 1977 Buick, and authorities believed he was targeted by members of the Young Turks faction, according to an Inquirer report from the time.

Retaliation was swift. Two months later, gunmen attempted to assassinate Michael Ciancaglini at his home near 12th and McKean Streets — just steps south of where Bocchino was killed. In that incident, the Daily News reported, Ciancaglini was returning home from a basketball game when two men carrying shotguns began chasing him. He made it inside, and the gunmen fired shotgun blasts through the front door and window.

Ciancaglini was not injured, and neither were his wife and two children, who were inside the house. Law enforcement sources told the People Paper that Ciancaglini “had something to do with Bocchino’s death,” but Ciancaglini’s attorney maintained his client was in the dark about the attempt on his life.

“He don’t know why. He don’t know who. And he don’t know what,” attorney Joseph C. Santaguida told The Inquirer following the shooting.

All-out war

In March 1993, almost exactly a year after the attempt on Michael Ciancaglini’s life, older brother Joseph Ciancaglini, 35, was shot at the Warfield Breakfast and Lunch Express in Grays Ferry. The attempted hit on Stanfa’s underboss was captured on FBI surveillance video.

Though he survived, Joseph Ciancaglini became permanently paralyzed.

On Aug. 5, 1993, the warfare arrived on the 600 block of Catharine Street with an afternoon shooting that injured Merlino and killed Michael Ciancaglini. The pair were walking down the block when two gunmen began firing, striking Merlino in the leg and buttocks, and Ciancaglini in the heart, reports from the time indicate. Ciancaglini died at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, while Merlino was placed in stable condition at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.

The car used in the shooting, meanwhile, was found some 35 blocks away, burned to a crisp. It had been leased to Philip Colletti, a mob associate who later admitted his role in the crime.

Hundreds attended Ciancaglini’s viewing at the Carto Funeral Home at Broad and Jackson days later; some neighborhood residents were not surprised by his killing, The Inquirer reported.

“Why’d he get killed? The same reason the rest of these hoods in South Philly do,” said one South Philly hairdresser. “Most Italians are good, hard-working people, and these people give us a bad name.”

An attempt on Stanfa

By the end of August 1993, the Young Turks struck back — this time with a botched assassination attempt on Stanfa himself that ended up wounding the mob boss’ son, Joseph, who was 23 and not involved with mafia activities.

That attempt took place during the morning rush hour as Stanfa and his son traveled from their home in Medford to their food importing business in South Philadelphia. As they drove toward the Vare Avenue off-ramp on the Schuylkill Expressway, gunmen ambushed them from a van that had been modified with makeshift gunports, allowing the assailants to fire from concealment.

» READ MORE: In the 1990s mob wars, John Stanfa didn’t have a nickname. The Daily News tried to change that.

The attackers, police later learned, had not cut eye holes in the van, and fired on the Stanfas wildly, missing their intended target. The younger Stanfa, however, was struck in the face, leaving a bullet lodged in his neck though he survived.

The van was found near 29th and Mifflin Streets as police attempted to reconstruct possible escape routes. It was littered with spent cartridges, and had “a number of punctures in it,” leading police to believe that a shooter lost control of his weapon, tearing bullet holes into the vehicle.

Stanfa’s vehicle, meanwhile, was heavily damaged, with at least 10 bullet holes running from the front hood to the right rear fender. A tire was shredded, and a window panel in the rear-passenger side — where Joseph had been sitting — was shattered. Stanfa, The Inquirer reported at the time, had his driver hide the car in the garage of the restaurant where Joseph Ciancaglini had been shot, requiring police to obtain a warrant to examine it.

“You’ve got to understand: This is an all-out mob war,” said Col. Justin J. Dintino, superintendent of the New Jersey State Police. ”They’re going to take their shot whenever the opportunity presents itself.”

Murder at the Melrose

In September 1993, the opportunity presented itself at the Melrose Diner, where Frank Baldino Sr., a reportedly low-level associate of the Young Turks, was shot to death in his car. His last meal was a $6.95 chopped steak dinner, the Daily News reported.

Gunmen approached Baldino’s vehicle, investigators said, and “pumped several bullets” through its closed window, striking him in the head and torso. The assailants fled west on Passyunk Avenue in a rainstorm, and Baldino died while en route to the hospital.

Baldino was not considered to be a major player in the local mob. His killing, friends and investigators said, was something of a shock — even former mobster Nicholas “Nicky Crow” Caramandi, who was in hiding at the time, denounced it.

“This guy was not a gangster,” Caramandi told The Inquirer. “He wouldn’t hurt anybody. He was not a threat. It should never have happened.”

A mafia hitman turns informant

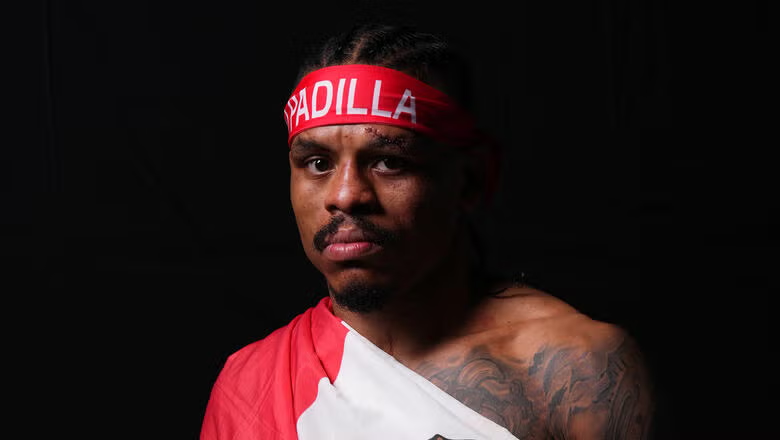

Though mob violence cooled as 1993 wore on, it didn’t fully stop, and late one Friday in January 1994, police found John Veasey near Sixth and Sigel Streets, grievously injured.

He had three bullet wounds to his head, one to his chest, and seven stab wounds, having fought off his attackers in an assassination attempt in the apartment above a nearby meat store. Somehow Veasey, then 28, had survived, and was placed in critical but stable condition at Jefferson Hospital.

“He’s a tough kid,” one underworld source told The Inquirer. “He knows a lot, and what he knows can hurt a lot of people.”

Veasey, it turned out, had gone to the FBI days before and copped to the Ciancaglini and Baldino killings at the behest of his brother, William “Billy” Veasey, who had told him there was a contract out on John Veasey’s life.

» READ MORE: What to know about John Veasey, the hitman-turned-informant in Netflix’s ‘Mob War’

His assailants, Veasey told police, were Stanfa loyalists Frank Martines and Vincent “Al Pajamas” Pagano, both of which later surrendered.

The pair, John Veasey said, had lured him to a mob-run “numbers house” under the guise of protecting him. But once inside, Martines pulled a gun and shot him in the head and chest, telling him, “Bye, John-John.” When that failed to kill Veasey, a battle ensued in which Veasey wrestled a knife away from Pagano, and used it to slash Martines in the eye.

“I have a real powerful neck, real, real big,” Veasey later said of his survival, according to a Daily News report. “I was not knocked out. It wasn’t sending any messages to the brain.”

The killing of Billy Veasey

Following the attack on Veasey, Stanfa and 23 associates were indicted on federal racketeering charges and imprisoned by March 1994. As the legal proceedings wore on, mob violence in the city trickled almost to a stop — with one notable exception.

On Oct. 5, 1995, just hours before Veasey was set to take the witness stand against Stanfa and his codefendants, his brother Billy was shot and killed on the 1700 block of Oregon Avenue.

Veasey was distraught, but his resolve to testify was hardened by the killing, law enforcement sources said. Five days later, he did just that.

Delivering his testimony in what The Inquirer called “South Philadelphia tough-guy jargon,” Veasey made the federal government’s case clear — in some cases, graphically so — for jurors. Calling himself a triggerman for Stanfa, he testified that the mob boss had given orders in 1993 to kill anyone who was aligned with Merlino and the Young Turks faction, and that a hit list with more than a dozen names had been circulated to mob members.

“A couple of [defense] lawyers tried to catch him up in semantics,” one federal source told The Inquirer of Veasey. “John doesn’t even know what semantics means.”

The war’s end

By November 1995, Stanfa and his associates were convicted on all counts, including murder, extortion, gambling, and kidnapping. Stanfa received five life sentences, and, at 84, remains in prison.

With that, the Young Turks had officially won the war. According to Inquirer and Daily News reports from the time, Ralph Natale had been installed as the head of the Philadelphia mob but focused his efforts on South Jersey, allegedly leaving Merlino and his cohorts to run South Philadelphia.

Following Natale’s arrest on a parole violation in 1998, Daily News and Inquirer reports from the time indicate, Merlino purportedly took over as acting mob boss, and later cut out Natale completely. Merlino himself was arrested on drug conspiracy charges in 1999, and Natale served as a government witness against him.

Ultimately, Merlino received a 14-year sentence after being convicted of racketeering. He was acquitted of drug trafficking and murder charges, the latter for which prosecutors initially considered pursuing the death penalty. With credit for two and a half years served, he was to spend nine more years in prison.

“It ain’t bad,” Merlino said of the verdict, according to an Inquirer report. “Nine’s better than a death penalty.”

“Mob Wars” is a three-part series on Netflix. Its release date is Wednesday, Oct. 22.