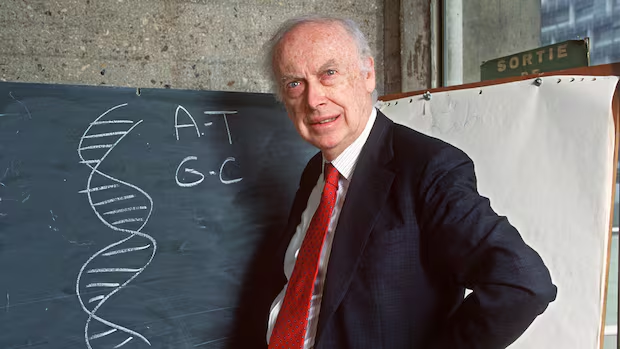

James Watson, co-discoverer of DNA’s double-helix shape, dead at 97

Listen to this article

Estimated 5 minutes

The audio version of this article is generated by text-to-speech, a technology based on artificial intelligence.

James D. Watson, the brilliant but controversial American biologist whose 1953 discovery of the structure of DNA, the molecule of heredity, ushered in the age of genetics and provided the foundation for the biotechnology revolution of the late 20th century, has died at the age of 97.

His death was confirmed by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island, where he worked for many years. The New York Times reported that Watson died this week at a hospice on Long Island.

In his later years, Watson’s reputation was tarnished by comments on genetics and race that led him to be ostracized by the scientific establishment.

Even as a younger man, he was known as much for his writing and for his enfant-terrible persona — including his willingness to use another scientist’s data to advance his own career — as for his science.

His 1968 memoir, The Double Helix, was a racy, take-no-prisoners account of how he and British physicist Francis Crick were first to determine the three-dimensional shape of DNA. The achievement won the duo a share of the 1962 Nobel Prize in medicine and eventually would lead to genetic engineering, gene therapy and other DNA-based medicine and technology.

Crick complained that the book “grossly invaded my privacy” and another colleague, Maurice Wilkins, objected to what he called a “distorted and unfavorable image of scientists” as ambitious schemers willing to deceive colleagues and competitors in order to make a discovery.

In addition, Watson and Crick, who did their research at Cambridge University in England, were widely criticized for using raw data collected by X-ray crystallographer Rosalind Franklin to construct their model of DNA — as two intertwined staircases — without fully acknowledging her contribution. As Watson put it in Double Helix, scientific research feels “the contradictory pulls of ambition and the sense of fair play.”

WATCH | The promise of gene-editing technology:

U.S. baby healed with tailor-made therapy using Canadian technology

A Pennsylvania baby with a rare genetic condition has been successfully treated with a tailor-made therapy using gene-editing technology partly developed by a Vancouver-based company, raising hopes it can be used for multiple conditions.

In 2007, Watson again caused widespread anger when he told the Times of London that he believed testing indicated the intelligence of Africans was “not really … the same as ours.”

Accused of promoting long-discredited racist theories, he was shortly afterwards forced to retire from his post as chancellor of New York’s Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL). Although he later apologized, he made similar comments in a 2019 documentary.

Winding staircase modelled

James Dewey Watson was born in Chicago on April 6, 1928, and graduated from the University of Chicago in 1947 with a zoology degree. He received his doctorate from Indiana University, where he focused on genetics. In 1951, he joined Cambridge’s Cavendish Lab, where he met Crick and began the quest for the structural chemistry of DNA.

The double helix opened the doors to the genetics revolution. In the structure Crick and Watson proposed, the steps of the winding staircase were made of pairs of chemicals called nucleotides or bases. As they noted at the end of their 1953 paper, “It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material.”

That sentence, often called the greatest understatement in the history of biology, meant that the base-and-helix structure provided the mechanism by which genetic information can be precisely copied from one generation to the next. That understanding led to the discovery of genetic engineering and numerous other DNA techniques.

Watson and Crick went their separate ways after their DNA research. Watson was only 25 years old then and while he never made another scientific discovery approaching the significance of the double helix, he remained a scientific force.

“He had to figure out what to do with his life after achieving what he did at such a young age,” biologist Mark Ptashne, who met Watson in the 1960s and remained a friend, told Reuters in a 2012 interview. “He figured out how to do things that played to his strength.”

That strength was playing “the tough Irishman,” as Ptashne put it, to become one of the leaders of the U.S. leap to the forefront of molecular biology. Watson joined the biology department at Harvard University in 1956.

From 1988 to 1992, Watson directed the federal effort in the U.S. to identify the detailed makeup of human DNA. He created the project’s huge investment in ethics research by simply announcing it at a news conference. He later said it was “probably the wisest thing I’ve done over the past decade.”

Watson was on hand at the White House in 2000 for the announcement that the federal project had completed an important goal: a “working draft” of the human genome, basically a road map to an estimated 90 per cent of human genes.

Researchers presented Watson with the detailed description of his own genome in 2007. It was one of the first genomes of an individual to be deciphered.