Dwayne Johnson, Emily Blunt and Benny Safdie’s Underdog ‘The Smashing Machine’: In a Topsy-Turvy Year, Don’t Count Them Out for Oscars Glory

The Rock had won over Christopher Nolan.

The “Oppenheimer” director, hardly known for making effusive public comments, was interviewing Benny Safdie about his new film “The Smashing Machine” at a Directors Guild of America screening in Los Angeles. Nolan gushed over Dwayne Johnson’s portrayal of MMA fighter Mark Kerr. “I think it’s an incredible performance,” he said, calling the portrayal “heartbreaking.” He went on: “I don’t think you’ll see a better performance this year or most other years.”

The comments were widely picked up, in part because they went against conventional wisdom: The screening was on Oct. 5, the Sunday of “The Smashing Machine”’s opening weekend, and when the film launched to an underwhelming $6 million in 3,300 theaters, many Oscar-race prognosticators left it for dead. But what hasn’t been widely known is that Johnson himself was sitting in the audience at the DGA, hearing an already-legendary director sing his praises.

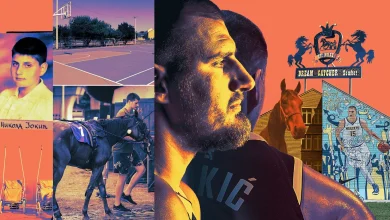

Emilio Madrid for Variety

“It was the most inspiring thing anyone has ever said about me,” Johnson, 53, tells me on Oct. 31. We’re speaking for a second time, after meeting before the film’s release, to reflect on the experience of “The Smashing Machine” being out in the world. Nolan’s praise wasn’t novel; Johnson says friends across the industry have come up to him to laud his work, and that Matt Damon, in particular, told him, “In what we do, we’re lucky enough, sometimes, to make a film that endures.” But the setting and the timing of Nolan’s words touched him deeply.

“Once it started to sink in, I was having an out-of-body experience,” Johnson says. “I was sitting next to my wife” — singer Lauren Hashian — “and I grabbed her hand so hard, and she squeezed my hand back.” Afterward, backstage, Hashian insisted that he “actually speak, like a human being,” to Nolan.

“I just gave him the biggest hug and the biggest kiss on the cheek,” Johnson says. “All I could say was ‘Thank you.’ And he said, ‘I meant what I said. You were heartbreaking, and the best performance of the year.’ I gave him another hug. That was all I could muster.”

Before he shot “The Smashing Machine,” a character drama with an indie soul, Johnson rarely allowed himself to be at a loss for words. He’s been known for playing guys who exude a confidence that, were it not so very appealing, might read as ego. Until now, the former wrestler’s biggest artistic risks have been an early role in “Southland Tales” and the dark comedy “Pain & Gain ” — and that was a Michael Bay film. Johnson refers to his career until “The Smashing Machine” as a “comfort zone,” and his audience took comfort in it too: One always knew, before the movie began, what one was getting from Johnson.

Since emerging as the greatest crossover star WWE ever minted (he retired for good in 2019), Johnson has carried franchises from “Jumanji” to “The Fast and the Furious.” Parents of young children know him as the “Moana” antagonist-turned-ally who boastfully declares, “You’re welcome!” before being thanked. But “The Smashing Machine” reinvented him twice over — first, in giving him a complicated, angst-ridden character to play, and now, as the campaign continues and Johnson asks his peers to give the film a second look, in positioning Johnson as the one doing the thanking. Experimentation, as audiences who continue to discover “The Smashing Machine” have learned, looks good on Johnson; so, too, does taking a blow but refusing to be counted out. “You always want more people to experience the film theatrically,” Johnson says stoically. But Damon’s words have stuck with him. “We’re going to have a film that endures: That wasn’t in my vernacular. But it is that kind of movie.”

Indeed, Safdie’s minor-key approach feels timeless. A big, brash fighting movie this isn’t; it also lacks the zany energy of the films Safdie has co-directed with his brother, Josh, like the antic thrillers “Good Time” with Robert Pattinson and “Uncut Gems” with Adam Sandler. Instead, the film takes a delicate approach to the pain Kerr must learn to live with. And if “The Smashing Machine” endures, it will be in no small part thanks to the places Johnson goes. Johnson’s character was a grappler who conquered drug addiction, relationship troubles and disappointments in the ring; like “Rocky” (the one that won best picture, not its increasingly fan-servicey sequels), “The Smashing Machine” ends with its hero in defeat, but looking hopefully to the future.

Johnson knows how that feels now. “The story of Mark Kerr rings more true,” he says. “It cuts deeper as we roll along on the journey of this film.” A week after the release, Johnson says, “I realized, Let’s do our best. Let’s be real. Let’s endure. This is a long game. And we made a film that is the underdog.”

In 2025, the indie movie business has all but collapsed. “The Smashing Machine,” which cost a reported $50 million, will lose money at the box office for A24. And it was the first of several mid-budget “dramas for adults” this season to fall short of expectations. From “Kiss of the Spider Woman” to “After the Hunt” to “Roofman” to “Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere,” fall has been a season of star vehicles that played to disappointing attendance. A certain kind of movie just may not be the kind of thing audiences go to theaters for anymore. Which means that box office may be less important than ever as Oscar voters sift through to find what stands out.

Emilio Madrid for Variety

When I meet the director and stars of “The Smashing Machine” for the first time in the week of the film’s release, all of that analysis lies ahead. We’re sitting in folding chairs in the middle of a boxing ring, in a downtown Manhattan gym chosen for its resemblance to the rooms Kerr haunts in “The Smashing Machine.”

Even before the movie comes out, the cast is aware of the shrinking theatrical environment. “A film like this that defies the curation system makes me so proud,” Emily Blunt, Johnson’s co-star, says. “I know it is getting rarer and rarer. You can’t persuade people to go see a movie anymore without a great story. I think word of mouth will be really exciting, and I hope that it can stretch out and many people can experience it.”

Safdie, an obsessive about accuracy, marvels at the grit and patina of the space. (He shot scenes for “The Smashing Machine” at a working MMA gym in Vancouver.) All three, dressed in formalwear for a photo shoot but with a joking, easy manner together, seem at home — this journalist, less so. (The only time I see Johnson lose his famous composure is when I trip and fall trying to climb through the ropes back out of the ring. “Easy! Easy!” he bellows, catching my arm.)

The fans set up to cool the space are overwhelming my recorder. So we turn them off and bear the heat. Safdie has sweat through his powder blue Gucci shirt, and Blunt periodically dabs Johnson’s head with a towel. The temperature and stench of the gym draws Blunt’s memory back to the production, when her character, Dawn Staples, rooted on her man in grotty little gyms as he made his name. “Smell of glove, smell of crotch,” she says.

Blunt had helped forge the connection that got the project made. Johnson had long been obsessed with a 2002 documentary about Kerr, also called “The Smashing Machine,” and Blunt, his co-star in the 2021 family film “Jungle Cruise,” suggested Johnson bring the idea of adapting it to Safdie. (Blunt and Safdie had acted together in “Oppenheimer.”)

“I feel like I was sort of the matchmaker for them dating,” Blunt says. “I didn’t want to sort of muscle my way into it.” She ended up getting cast anyway. The “fighter’s girlfriend” is a familiar trope; Heidi Gardner lampooned it on “Saturday Night Live,” pleading with her man to drop out of the big match. Dawn’s angst is more nuanced: She is genuinely impressed by what Mark can do, but she wants, with growing urgency, to feel like a part of his triumph. “The ‘girlfriend’ role — I don’t feel we straitjacketed her to that,” Blunt says, “because of Benny’s interest in seeing the full spectrum of every human being in the movie.”

Blunt spent time with the real Staples, who was skittish about the film: “The Smashing Machine” covers a low period of her life, and she and Kerr are no longer together. “The gloves were up at first — because the documentary was made under a male gaze,” Blunt says. Staples felt she’d been forced into an impossible position in her time with Kerr: “Dawn was the one into which he decanted all his stress and addiction.” The relationship, in which Kerr and Staples took their demons out on one another, was broken. But it was real, too, and Staples wanted Blunt to be its advocate. “She wanted us to protect that — to show the tender moments, show the love, show the devotion. Yes, the devotion was mixed with destruction, but it still existed.”

Blunt has negotiated relationship dynamics on-screen before: Her Kitty Oppenheimer shows how spiky and complex a “wife of” character can be. Johnson, by contrast, felt a fundamental discomfort in shifting what he could do. Gaining 30 pounds of muscle and sitting for daily prosthetic applications wasn’t what he dreaded. The fear factor was the idea of digging into character.

“I was in a comfort zone for quite some time,” Johnson says. “Making these big films — they’re hard to do, but they are comfortable. What I was scared of was exposing myself and exploring the deepest, darkest traumas.”

Blunt had brought Safdie to the project. And she helped keep it from falling apart. Since first working together, she and Johnson had become close friends. (She casually picks up his energy drink and sips at one point, and jokes in an aside that “our ‘Jungle Cruise’ press tour almost got shut down by Disney because we were so inappropriate.”) In moments when Johnson hesitated, she urged him on. “I used to have this motto — ‘Audience first,’” Johnson says. The audience, he believed, didn’t want him to take a risk. Blunt disagreed. “Emily said, ‘I love that. It’s worked for you for decades now. But if you want to take care of the audience, show them a mirror of yourself. Isn’t that taking care of the audience too?’”

Emilio Madrid for Variety

“It may not seem like it, but I have that same motto,” Safdie says. The film was aggressively test-marketed, and Safdie read every comment. Among the trickier elements of the film was Mark and Dawn’s relationship. Dawn is not equipped to date an addict in recovery, and Mark’s pursuit of the limelight doesn’t help matters either; her need for attention turns increasingly self-destructive. “I wanted the relationship to be people,” Safdie continues. “I wanted both of them to be at fault. And I wanted people to feel good at the end.”

To the first goal, Safdie’s shooting style lent the arguments between Mark and Dawn a special realism. In the characters’ home, Safdie used hidden cameras to keep the actors in the moment and not let them play to a particular angle. “I always want to stay out of the way,” the director says. “I want them to just be present.”

“It adds this reality,” Blunt says, “like maybe we shouldn’t be watching — like we’re being voyeuristic. I was grateful I didn’t see cameras shooting. When I saw the film, I felt like its arms came out and pulled me inside of it. It was so visceral.”

As for allowing the audience to leave feeling good — that’s a tall order, given the subject matter. And yet an extended cameo from the real Kerr in the film’s closing moments makes clear: He survived it all, and is now OK.

“People can’t relate to the guy with his fist in the air at the end,” Blunt says. “But they can relate to the peace of being OK with yourself despite this brutal life. None of us relate to being the heavyweight champ of the world, but we all relate to struggle, and we all relate to pressure.”

Kerr’s story, as told by Safdie, Johnson and Blunt, first reached the world at the Venice Film Festival, where it won the best director prize from Alexander Payne’s jury and received a 15-minute standing ovation. During the applause, Johnson burst into tears.

What was he thinking in that moment? “It’s hard to find the language for it, because it’s so emotional,” he says. “It was just validation of this seemingly once-in-a-lifetime journey. Not only for us, but also for the man who actually lived it.” Kerr was sitting next to Johnson in what the actor calls “the small seats” (though if you’re Johnson or Kerr, perhaps every seat feels small). “He was shaking throughout the film — and that final 15 minutes of the film, the emotional excavation, he’s really crying.” Johnson notes that today, fighters make millions of dollars and become famous. (He would know.) Kerr didn’t have that kind of spotlight, and he got one at Venice. “I was so happy for Mark, that audience telling him, You lived a life. And we all see ourselves in your life.”

Kerr’s relatable — but he’s also, plainly, one of a kind. To play him, Johnson had to transform his already-imposing frame to achieve the look of an MMA fighter. “Mark had a unicorn body,” he says. “His traps, his shoulders, his quads: Because of being a wrestler, he’s always doing takedowns, but it’s very fast-twitch fibers, so I had to put on that quality of muscle while being able to move.”

“That tight waist is so hard when you’re gaining weight!” Safdie says as Johnson laughs ruefully. “Oh my God!”

While Johnson’s body changed in a major way, the prosthetic transformation was more subtle. Safdie decided to go to a “middle ground” in terms of how far to push Johnson toward Kerr’s visage — Johnson looks incrementally more like the man he’s playing, but he isn’t lost either. “I remember talking to Dwayne and saying, ‘I want you to come through. Because I know that you’re exploring a lot of yourself in this movie. And I don’t want that to be missed.’” (And in Kerr, viewers see a bit of Safdie too — the hirsute director jokes that he sent prosthetic makeup artist Kazu Hiro a photo of his own eyebrows as a reference.)

Emilio Madrid for Variety

Johnson’s own brows were so famous, in his WWE era, that “the People’s Eyebrow” was his trademark. His willingness to hide them, and to shift his appearance at all, emphasizes how much of a pivot point this is for Johnson: It’s a first-ever bet on his ability to disappear into character. But the film is a shift for his colleagues too: For Blunt, at 42, it’s more proof that she is willing to take on challenging auteur work ahead of next year’s one-two punch of an as-yet-untitled Steven Spielberg action film and “The Devil Wears Prada 2.” And for Safdie, 39, it’s his first solo feature film. “The Smashing Machine”’s opening weekend came just before a triumphant surprise screening of “Marty Supreme,” A24’s other 2025 sports drama directed by a Safdie, at the New York Film Festival. The coincidence fueled persistent speculation that the brothers, careerlong collaborators until Benny shot the 2023 TV series “The Curse,” had broken up acrimoniously. Safdie’s acceptance speech in Venice, in which he thanked his mother, stepfather, wife and children — but not Josh — furthered the chatter.

Safdie seems unfazed by the conjecture, but mildly surprised that it keeps coming up. “In that moment, I was thinking about this movie,” he says.

“It’s also your night,” Blunt says.

“I was talking about this movie. That’s where that came from.” The gossip about a rift, he says, “was shocking. Like, Oh, wow, that’s weird.”

“Did people react like that? That’s so weird,” Blunt says. “You are allowed to be a single entity.”

“We did great things together, and we learned in that process, and it just came to a place where it’s like, What do you want to explore, and what do I want to explore? And you just do that.” (When we speak, Safdie hasn’t yet seen “Marty Supreme,” but says that his brother has seen “The Smashing Machine.”)

Johnson is doing a different sort of setting out on his own: After years of trusting his philosophy of serving moviegoers what they’ve been trained to expect, he’s now daring them to come along for a melancholy yet exhilarating ride.

“These guys know this,” Johnson says. “For me, this has not been my …” He seems to lose his train of thought, and begins again. “Opening week. This is opening week. I had not experienced this until this film — I have not thought about box office once. Not once.”

“What a relief,” Blunt says. In conversation, she has a tendency to pick up the threads Johnson drops. “You also know that if the movie doesn’t work, they’re coming for you, and it is personal — and it hurts that it’s personal. But there’s a myriad of other reasons why a movie might not work, but they would come swinging for you. Exposure to that is not really for the faint of heart.”

“But there’s a real beauty in that,” Johnson says. “Like Mark Kerr — we’re OK.”

And he has no regrets. The experience of making the film has “completely changed everything,” he says. “In ways that I could expect, perhaps in ways that I was hoping. But it completely changed the way I look at stories.” For decades, Johnson was a leading man for hire. Now, bruised but undefeated, he’s looking at captaining his own projects.

“From ‘Smashing Machine’ forward,” he says, “I will make movies for me. Because they’re my dream. Not anyone else’s.”

One such dream is “Lizard Music,” Benny Safdie’s next film. It’s an adaptation of Daniel Pinkwater’s anarchic 1976 young-adult novel about a child left home alone who hears music coming from another dimension. (When we Zoom in late October, Johnson has his copy just out of frame, pulling it in when I mention the title. “I always keep it close!” he laughs.)

Young Victor, in the story, enlists the oddball Chicken Man (Johnson) to help figure out the source of this otherworldly music. Like many YA books of its era, it presumes a certain level of sophistication, and curiosity, on the part of the reader.

“There’s something about what that book does to kids,” Safdie says. “It gives them a license to feel independent.”

“I am that little kid,” Johnson says. “To watch my parents go through these things and to clearly see that things weren’t great.”

“Can I be a lizard?” Blunt asks, to lighten the mood. “I’ll be any lizard you want!”

It was another aspect of Johnson’s life story that made it into his performance — and that Christopher Nolan spotted. Johnson recalls that the director made special mention of the way Johnson, in character, reacted when confronted over his drug use by his best friend (played by real-life mixed martial artist Ryan Bader). Lying in a hospital bed, Johnson’s Mark pulls the sheets over his head, so as not to be seen crying. “If I say to you, ‘I understand,’ what I’m saying is I’ve lived it,” he says. “I’ve reached this point in my life, my fifth level, where if I say I understand, that’s because I’ve lived it. I lived that moment.”

Johnson had been with his mother when she received a diagnosis of Stage 3 lung cancer. “When you’re diagnosed with that, you have to start planning things you don’t want to plan,” he says. “The doctor comes in and says, ‘We’re going to do our best to take care of you.’ In that moment, she pulled her sheets over her face and just starts bawling.” Johnson had seen his mother cry before, but never like this: “It’s almost like she got reduced to being a little girl, just wanting to hide away.” Johnson did something his franchise movies had never compelled him to do. “I took that moment,” he says, “and applied it.”

To permit oneself to go to a place like that requires vulnerability — no easy thing for a man whose stock-in-trade has been toughness. “What this has allowed me to do — and perhaps I didn’t realize this in the past — is, when I find something, whatever it is, I can give my complete heart and soul,” he says. “And I want and need them to be different from each other. I’m not looking to deliver more of the same. For decades, it was audience first. But the thing that sets my soul first is an idea of audience first as my full self. My complete self.”

This is deep into my second conversation with Johnson, and I’m surprised by these words, this insistence on new challenges from the king of the franchises, despite my familiarity with him by now — so much so that I refocus my eyes on the Zoom window. There he is, the same figure I’ve seen so many times before: shiny dome, broad shoulders. His long-sleeved T-shirt is printed with what may as well be a new slogan for a film that’s been against the ropes, but isn’t out yet. It reads, “Vanquish.”