“Hamnet” Feels Elemental, but Is It Just Highly Effective Grief Porn?

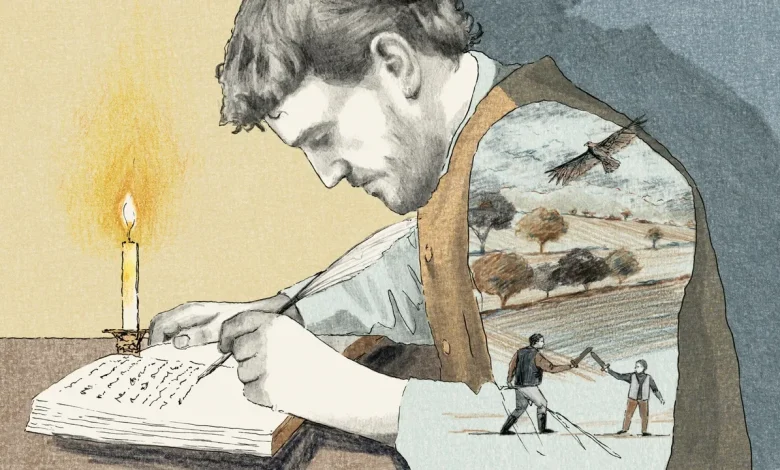

Zhao’s first three features were steeped in documentary realism, shot with a sturdy, windswept lyricism and abounding in nonprofessional actors. Then came her fourth picture, the clunky Marvel comic-book epic “Eternals” (2021)—a noble but self-evident failure, in which she channelled the visual and spiritual reveries of Terrence Malick, a longtime influence, in a vain attempt to transcend superhero-movie conventions. “Hamnet” is, inevitably, an improvement, though not exactly a return to form. It marks an unstable new mode for Zhao, a weave of subdued pastoral realism and forceful, sometimes pushy emotionalism. The movie whispers poetic sublimities in your ear one minute and tosses its prestige ambitions in your face the next.

The whiplash is disorienting, but, somewhat paradoxically, the characters’ romantic upheaval provides its own center of gravity. You are propelled alongside them as Agnes, sensing William’s creative and professional frustrations, packs him off to London to follow his dreams, hastening the pair’s descent into marital discontent and parental grief. Buckley is every inch the requisite force of nature, heaving and sweating up a storm as Agnes wrenches her children into this world, and moving swiftly from anguish to rage—a drained, defeated anger—as one of those children is yanked back out of it. Buckley and Mescal, both Irish and both bountifully gifted, have done quieter, subtler work elsewhere, though I can’t say that their histrionics miss the mark. What is “Hamnet,” or “Hamlet,” without a little ham?

O’Farrell’s novel is subtitled “A Novel of the Plague.” Its most gripping, least typical chapter describes an outbreak in breathlessly suspenseful detail, tracking the contagion from Alexandria, where a shipworker has a fateful encounter with a monkey’s fleas, all the way to England and, eventually, the Shakespeares’ doorstep. It’s no surprise that the film dispenses with this; its focus is on the domestic claustrophobia that William escapes and Agnes sacrificially endures. Agnes finds some comfort from her supportive brother Bartholomew (Joe Alwyn) and, in time, her mother-in-law, Mary (Emily Watson), who initially disapproves of Agnes but comes around to a grudging respect, rooted in shared experiences of drudgery and loss. This is Zhao’s first collaboration with the Polish cinematographer Łukasz Żal, who, in the Holocaust drama “The Zone of Interest” (2023), used an array of small hidden cameras to suggest the daily, routinized horrors of a Nazi family. “Hamnet” attempts nothing so technically virtuosic or historically queasy, and yet a not dissimilar air of home surveillance persists. Indoors, the Shakespeares are often shot unnaturally head on or in high-angled panoramas that diminish their stature. We could be studying them under glass.

Such intensity of focus may also explain why Zhao and O’Farrell have jettisoned the novel’s nonsequential narrative structure, which shuttles, quite intricately, between two parallel time frames. The film, by contrast, moves cleanly from start to finish, forgoing any impulse toward Malickian nonlinearity. Even so, Zhao remains vividly under the spell of Malick the image-maker, and also Malick the intimate observer of the everyday. She has a great eye for sunlight, especially when filtered through a woodsy canopy of green, and in the family’s happier moments she’s exquisitely attentive to the joyful chaos of Hamnet (Jacobi Jupe) and Judith (Olivia Lynes) at play. At one point, the kids pretend to be the Weird Sisters. Their father may be a fitful presence at home, but his work already has them under its spell.

But not Agnes. When Hamnet is gone, she increasingly resents her husband’s absences. This manifests itself not in fits of fury but in a silent indifference to the work that keeps William away, and we sense that “Hamnet” means to deliver a feminist corrective to the myth of male genius. But it’s a halfhearted rebuke; the movie does, in the end, give that genius its due, and with a compensatory haste that occasionally throws Mescal’s performance off balance. During rehearsals, the distracted, tormented playwright forces a young star (Noah Jupe) to run his lines ragged; later, strolling moodily along the Thames, William adopts Hamlet’s “To be, or not to be” soliloquy as his own. The play’s clearly still the thing, but its invocations here seem facile in the face of a father’s grief.

Shakespeare’s creation comes to life more effectively onstage, and with Agnes there to witness it. Until now, she has avoided the Globe like, well, the plague, and the mere act of theatregoing strikes her as alien. There’s a comic aspect to her confusion—chronic shushers will be triggered to the point of distraction—which only reveals the utterly guileless depth of Buckley’s absorption in the role. Agnes’s nescience encourages us to see “Hamlet”—staged here on a forest set that takes us back to the film’s Edenic beginning—through fresh eyes. My own, I confess, were soon blurred by tears, brought on with such diluvial force as to both quench my skepticism and reawaken it. There is, for starters, the shameless deployment of Max Richter’s “On the Nature of Daylight,” a lush track that, from “Shutter Island” (2010) to “Arrival” (2016), has grown hoary with overuse. There is, too, the inherent kitsch in reducing one of the richest, most intellectually prismatic works in English literature to an instrument of healing. “Hamlet” has been many things for many centuries; here, it is chiefly the vessel for a parent’s closure. The rigor of the text melts, thaws—and resolves itself into adieu. ♦