World AIDS Day: why HIV infections are still so hard to treat

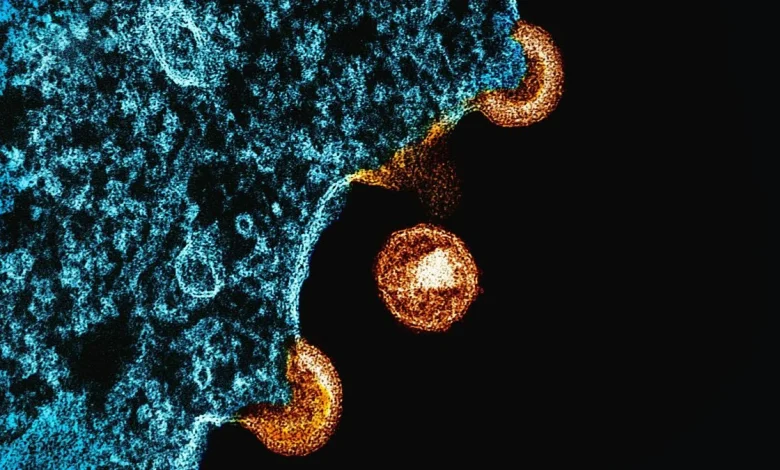

In a landmark paper in Science on May 20, 1983, researchers reported they had isolated a “retrovirus” from a patient at risk of developing AIDS. The work, led by French virologists Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Luc Montagnier at the Institut Pasteur, was the first glimpse of what would become one of the most devastating pathogens in modern human history.

At the time, neither Barré-Sinoussi nor Montagnier knew that they had isolated the emperor of all viruses.

In the years that followed, it became tragically clear the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), as it came to be known, was not ordinary. Patients who acquired HIV did not recover and every attempt to create a vaccine failed. If left untreated, the infection had a near-100% mortality rate, relentlessly destroying the immune system and leaving patients vulnerable to fatal opportunistic infections.

No vaccine, no cure

Today, more than four decades later, while HIV is no longer a death sentence, it remains far from cured. The virus has merely transitioned from a guarantee of death to a lifelong, tightly managed chronic illness. Survival today depends on strict, uninterrupted antiretroviral therapy — a regimen that comes with side effects and imposes the constant psychological burden of adherence, since any lapse risks viral rebound, with the added danger of the development of drug resistance.

Thus after 42 years of unprecedented investment of time, money, and scientific effort, we are left with a rather abysmal report card. There is still no vaccine. And of the estimated 91.4 million people who have ever been infected with HIV, only a handful of individuals have been declared “cured”. These rare cases were not cured by drugs but by bone-marrow transplants carried out to treat leukaemia, a form of blood cancer. Bone marrow transplants are risky procedures that are neither safe nor practical for the vast majority of persons living with HIV.

What makes HIV so resistant to a cure?

On guard for life

The answer lies in two unique properties of the virus. First, HIV belongs to a family of viruses called retroviruses. These viruses are unusual because, as part of their life cycle, they convert their genetic material from RNA to DNA, then integrate this DNA into the host’s own DNA. Once this happens, the viral DNA becomes, for all practical purposes, indistinguishable from your own. The virus becomes a part of you. The only definitive way to eliminate it would be to eliminate every single infected cell.

This challenge might still have been manageable were it not for the second property that makes HIV so formidable. After integrating its DNA into the host genome, HIV can enter a dormant state known as viral latency. In this state, an infected cell carries HIV’s genetic material but produces no new virus particles. The virus persists silently, invisible to the immune system. At any given time, some infected cells churn out new viruses while others slip into latency, creating a shifting, hidden reservoir that has so far made a true cure impossible.

This is also why antiretroviral therapy must be taken for life. The medicines merely prevent the virus from infecting new cells — but they do nothing against the silent, latent reservoir. They can’t. Once therapy is stopped, a portion of these dormant infected cells will inevitably reactivate, reigniting viral replication.

Together, these two properties make HIV uniquely difficult to cure. There are viruses that can integrate into the host genome: other retroviruses like HTLV-1 do this; even the hepatitis B virus sometimes leaves behind a stable DNA form in liver cells. There are also viruses that establish long-term latency: the herpes simplex and varicella-zoster viruses hide in nerve cells while the Epstein–Barr virus can persist silently in B-cells. And while a few viruses can even do both, none can do so with the efficiency observed in HIV.

Moving target

Despite HIV possessing several other traits that add to its resilience, none compare to the consequences of its integration and latency. HIV’s extraordinary sequence diversity, for example, is a hallmark of many RNA viruses. The hepatitis C, influenza, and some other viruses also mutate rapidly. But in HIV’s case, this diversity becomes far more dangerous because it operates on top of permanent genomic integration and deep latency.

That is, the virus constantly changes its appearance while simultaneously hiding inside long-lived cells, creating a moving target that the immune system can neither fully recognise nor completely eliminate. Over time, this relentless battle leads to immune exhaustion: the immune system becomes overwhelmed, depleted, and unable to keep up. This combination of rapid mutation layered onto integration and latency makes HIV one of the toughest pathogens humankind has ever encountered.

Fall as it lived

Yet even in this difficult battle, there are reasons for cautious optimism. Decades of public-health efforts ranging from information and education campaigns to widespread testing and the expansion of antiretroviral therapy have transformed the global response to HIV. Today, more people than ever before are on treatment, and with consistent use antiretroviral therapy not only keeps individuals healthy but also reduces the amount of virus in the blood to levels so low that transmission becomes virtually impossible.

Awareness is also higher than ever, people are getting diagnosed earlier, and treatment coverage continues to rise. As a result, the incidence of infections is falling year on year in many parts of the world, making room for hope against hope that an end to one of the worst pandemics to afflict humans may well be on the horizon.

From the very beginning, HIV has been exceptional. It defied every pattern we knew. It was a virus that destroyed the very immune cells meant to fight it, that integrated permanently into our DNA, and hid in silent reservoirs for decades, that resisted vaccines despite enormous global scientific mobilisation. Where other pathogens bent to human ingenuity, HIV forced us to rethink everything: diagnosis, therapy, prevention, even the limits of biomedical ambition.

Yet it may well be that the emperor of all viruses will finally fall — not to a cure but to awareness, prevention, and the steady narrowing of its paths of transmission. And in that fall, HIV may die as it lived, as the exception, as the one virus science could not conquer, but which was ultimately rendered powerless by humanity’s collective will.

Arun Panchapakesan is an assistant professor at the Y.R. Gaitonde Centre for AIDS Research and Education, Chennai.

Published – December 01, 2025 07:30 am IST