‘Marty Supreme’ Review: Timothée Chalamet’s Legendary Performance Anchors an Exhilarating American Epic About the True Cost of Greatness

Like many great actors and virtually all legitimate movie stars, Timothée Chalamet is a salesman at heart. But where most of them prefer to keep that like something of an open secret, the razor-cheeked Lisan al-Gaib — who’s become a brand unto himself, despite showing up at a time when Hollywood remains far more invested in franchises than faces — has embraced his entrepreneurial zeal with the same winning commitment that he brings to literally everything else he does.

It’s baked into the most basic essence of his image. Chalamet doesn’t co-own a mobile phone company or do an inordinate amount of commercial work (his ads are limited to Super Bowl spots and Scorsese collaborations), but whether accepting an award or simply delivering a turn worthy of one, he never shies away from the sense that he’s selling himself on screen. In that light, it’s no coincidence that his status as both a great actor and a legitimate movie star has grown increasingly undeniable the more that his performances have started to seem like pitches. Magic chocolates. Ancient prophecies. Electric folk songs. Limited edition track jackets. Whatever the product they’re trying to move, Chalamet’s recent characters don’t feel like roles so much as fences for his infectious self-belief. The poor kid was born with the hustle of a champion but saddled with the soul of an artist; Michael Jordan didn’t need an audience to affirm his greatness, but Chalamet’s legend requires us to buy him all over again with every shot.

The ecstatic tension at the heart of the world-beating “Marty Supreme,” in which Chalamet makes one of the most colossal movie performances of the 21st century seem as natural as a lay-up, is that it encourages modern Hollywood’s ultimate striver to sell his heart out, just so it can interrogate why anyone would bother trying so hard. It challenges — and rewards — his outspoken pursuit of greatness by casting him as a character who’s pathologically driven by the same thing.

Which isn’t to suggest that Josh Safdie’s A24 epic is best appreciated as a metatextual commentary on its star (much as it was obviously written both for and about him), or that a generational classic this overflowing with life should be reduced to another cautionary tale of someone flying too close to the sun, but rather to emphasize how thoroughly it suffuses Chalamet’s singular eagerness into a film as propulsive, quicksilver, and electrifying as he is. The result is a roman candle of a movie that feels like it was shot out of a cannon, despite being burdened with the gravity of an implausible dream; a totemic Jewish-American odyssey about where such dreams come from, where they might lead to, and where they’re liable to come apart at the seams along the way.

In Safdie and Ronald Bronstein’s splenetic wonder of a screenplay, mishegoss bleeds into madness when a 23-year-old 12-year-old named Marty Mauser — very, very loosely inspired by mid-century table tennis prodigy Marty Reisman — essentially decides that his personal destiny is the Jewish people’s reward for several millennia of suffering, a continuum that connects the pyramids of Egypt to the Lower East Side of Manhattan. It’s 1952 and the world is still picking itself up after the mess that Hitler left behind; it’s a time when everything and nothing seems possible for the generations of immigrants who’ve come to America for a better life. While we never quite learn how and when the Mauser family came to America (Marty is allergic to the past in all its forms), the film suggests that its indefatigable young hero feels the weight of history on his bird-like shoulders; six million Jews weren’t slaughtered so that he could hawk women’s shoes in the cramped little store that his uncle wants him to run like an honor.

Marty has bigger plans in mind. More specifically, he’s hellbent on becoming the greatest ping-pong player on planet Earth, and by the time we first meet him he’s already sold himself so hard on that purpose that all of the other people in his life are basically just the collateral required to finance his dream. Why ping-pong? Maybe it’s just because it’s a sport he can win — one that’s cheap to play, and attracts greasy oddballs like him to the local table tennis club where members can sleep on a cot in the back room whenever their lives spin out of control.

The reason doesn’t really matter. What matters is that withholding it from the audience makes it impossible to know where opportunism ends and passion begins, even, we suspect, for Marty himself (the way that Chalamet mutters “I love you” at the end of even the tensest arguments with his extended family is the kind of immaculately lived-in gracenote that this movie has by the hundred). Be that as it may, there’s no denying that Marty is completely and obsessively sincere in his desire to be the world champion, no matter how absurd that desire might seem to those around him. Or to us. It’s a need that runs deep in his DNA (as we see first-hand during a title sequence so hilarious that it tends to set off spontaneous bursts of applause), and Chalamet inhabits the character with the unflinching pathology of a Herzogian madman.

An inveterate liar in service to a higher and more ecstatic truth, Marty is equal parts Fitzcarraldo and Frank Abagnale Jr., with a sprinkle of John McEnroe and Joel Goodsen mixed in for good measure. Chalamet addictively synthesizes these overlapping energies into an irrepressible raconteur who thinks, acts, and self-destructs with the hurry of a hummingbird flapping his wings; he sells every single line of the film’s logorrheic screenplay without any concern for who might have to pay for it, or what it might cost them. Marty is a creature of the future, and he races around this movie as if he can’t wait another minute to get there.

‘Marty Supreme‘Courtesy Everett Collection

Much like the subject of Benny Safdie’s recent “The Smashing Machine,” the idea that the future might not be what he had imagined — the possibility of failure — never crosses his mind any more than whether or not the sun will come up the next day. Safdie’s ingenious decision to exclusively soundtrack this post-war period piece with 1980s bangers (Alphaville, Public Image Ltd., Tears for Fears, etc.) makes it feel as if Marty is in tune with a tomorrow that only he can hear, just as Daniel Lopatin’s synth-driven score — so intricate and voluble that it functions like a second screenplay — hurls Marty towards the horizon by tapping into an anxiety that period-appropriate music could never hope to match.

“Forever Young?” Not quite. Marty is precocious enough that he wears a trenchcoat like there should be two more kids stacked on top of him, but the threat of imminent fatherhood still follows him from the first scene of the film, in which he unknowingly impregnates his married girlfriend Rachel in the back of his uncle’s store before he steals away to London for the world championship (Rachel is played by Odessa A’zion in a breakout performance as Marty’s ultimate rally partner). He arrives in the U.K. convinced that the tournament will be his coronation, but a shock loss to Japanese superstar Koto Endo — played by Japanese National Deaf Table Tennis Championship Koto Kawaguchi, an especially gripping screen presence in a film where even the smallest roles are branded upon the brain — threatens to unmoor Marty from his sense of self. Spoiler alert to anyone who’s never seen “Good Time,” “Uncut Gems,” or “Heaven Knows What”: Safdie characters are dangerously attached to their idea of who they are, and they’re liable to do some pretty desperate things when their ecstasy is kept just out of reach.

Marty Mauser is no different, and he spirals out of control at a scale that makes the trials of Howard Ratner seem like a warm-up match. The gist of it is that he returns to NYC with just a few days to pay off $1,500 in fines and make his way to Japan in time for a rematch with Endo, but the plot thickens and convulses and mutates in all sorts of wild shapes from there. The journey is best understood through the people Marty steamrolls over along the way, all of them wonderfully dented in their own ways.

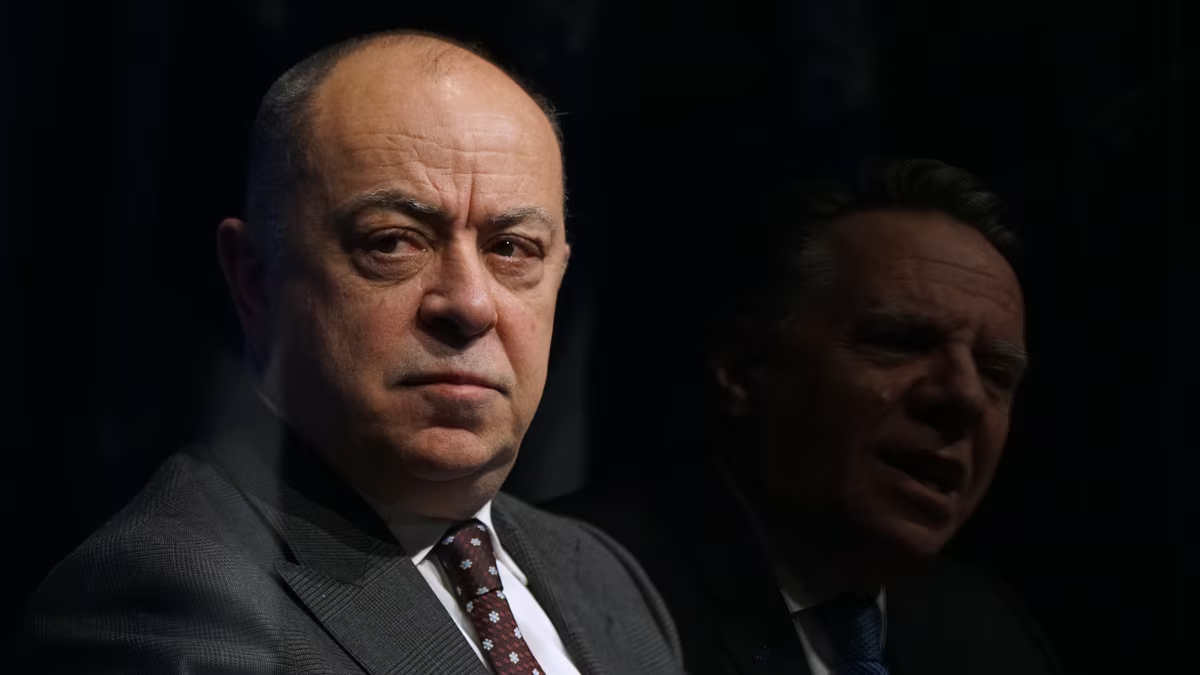

Chief among them would have to be faded Hollywood actress Kay Stone (Gwyneth Paltrow, returning to the screen from semi-retirement in a role that vividly recaptures the radiant stardom of her “Shakespeare in Love” days), the untouchable shiksa goddess Marty gloms onto as soon as he sees her stroll through the lobby of the Ritz with her ghoulish ink magnate husband, Milton Rockwell (“Shark Tank” star and hyper-capitalist money freak Kevin O’Leary, discomfortingly great in another brilliant flourish of meta-casting). Kay hasn’t acted since before Marty was born, and Marty never breaks character — they were made for a churlish May-December affair that unlocks something in them both.

‘Marty Supreme’

But Kay is just one of our boy’s many potential meal tickets. Another is his best friend Wally (rapper Tyler Okonma, just wild enough that Marty makes him seem like the voice of reason), a taxi driver who helps him hustle some kinda nice white yokels out in New Jersey after Marty comes home from a stint opening for the Harlem Globetrotters with Auschwitz survivor and previous table tennis champ Bela Kletzki (“Son of Saul” star Géza Röhrig). And then there’s the dog-loving gangster played by Abel Ferrara, who you clearly do not want to fuck with, and who Marty of course immediately fucks with in a moment of comic bliss straight out of “The Money Pit” that sets the entire movie careening in another direction. Penn Jillette, Fred Hechinger, Fran Drescher, Emory Cohen, and nearly 100 other faces you’ll never mistake again factor into the mix by the end — all of them have the misfortune of standing between Marty and his greatness, even if most of them are latently instrumental to it.

Sequences metastasize out of each other like fast-growing tumors as the script hides a cosmic design that only reveals itself in hindsight, making it rewarding for us — and almost impossible for Marty — to recognize that his legend is the sum total of the people he steamrolls on his way to achieve it, just as his personal destiny is built on the back of an entire diaspora. “It’s every man for himself where I come from,” Marty likes to bark; he thinks he’s the main character of an unfettered ode to American individualism (the ambition it can fuel, and the narcissism it can breed), when really the movie around him is more of a thick-skinned but soft-hearted critique of it. When really the movie around him is just a towering prologue to someone else’s story. Or, as it pertains to Endo’s stoic and selfless quest for post-war renewal, a bizarro parody of it.

Both of Safdie’s children were born in the span between “Uncut Gems” and “Marty Supreme,” and the biggest difference between the two films — besides the budget and sheer majesty of the latter, whose ultra-real Jack Fisk reproduction of the old Lower East Side makes it feel like Timothée Chalamet fell into a lush New Hollywood masterpiece — is that it’s ultimately more in service to growth than self-negation. It’s a movie about how agonizing and sublime it can be for terminally driven people to start living for something bigger than themselves.

While “Uncut Gems” starts in its hero’s asshole and ends in the back of his head, “Marty Supreme” is a lot more open-ended. Marty Mauser is no less rapacious than Howard Ratner, but he’s gripped by a dream instead of an addiction, and while Safdie obviously gets off on following Marty deeper and deeper down the rabbit hole of his own deranged vision quest, the real thrill of this movie — which accrues an immense emotional undertow by its final scenes — is in watching Marty tunnel out the other side. In watching him figure out, on his own naive terms, that “every man for himself” can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. In watching him learn first-hand how easily the pursuit of success can become just another recipe for solipsism. The American Dream is just another slogan, and being the best salesman below 14th Street doesn’t protect Safdie’s protagonist from the possibility that he might also be the area’s biggest mark. Marty might like to think of himself as “the ultimate product of Hitler’s defeat,” but the greatness of this movie is in how Chalamet’s performance gradually sells us on the idea that he doesn’t have to be.

Grade: A

A24 will release “Marty Supreme” on 70mm in select theaters on Friday, December 18. The film will be released nationwide on Christmas Day.

Want to stay up to date on IndieWire’s film reviews and critical thoughts? Subscribe here to our newly launched newsletter, In Review by David Ehrlich, in which our Chief Film Critic and Head Reviews Editor rounds up the best new reviews and streaming picks along with some exclusive musings — all only available to subscribers.