‘It changed my boys’ life’: These parents are fighting for one of Cleveland’s smallest schools

When he started speaking at the school board meeting on Nov. 19, Jonathan Salazar had spent weeks preparing for his allotted three minutes.

He had laid awake at night trying to find the right words that walked the line between passionate and disrespectful. He set an early morning alarm to secure a speaking slot after being unable to give public comment a month earlier because he hadn’t known to sign up ahead of time.

By the time he made it to the microphone, the Cleveland Metropolitan School District had already announced that Louisa May Alcott, the school Salazar’s twins currently attend, was on the list of 18 schools recommended to close next year.

Salazar thanked the board and began to explain why Alcott needed to stay open. His voice rose with every sentence as he described how the school’s small class sizes and dedicated staff had helped his two sons, both of whom have special needs, flourish.

“It changed my life,” he said. “It changed my boys’ life.”

Jonathan Salazar gives public comment at school board meeting on Wednesday Nov. 19, 2025. Credit: Franziska Wild.

Salazar had been rallying parents, teachers and other community members around saving Alcott since before CMSD officially announced its plan to merge 39 schools, resulting in 18 closures. By doing so, the district hopes to save money on older, half-full school buildings, allowing it to increase academic offerings at the remaining schools.

Should the school board vote to approve the plan on Dec. 9, next year Alcott would merge with Waverly Elementary and Joseph Gallagher Elementary into Gallagher’s building — forming a school community nearly six times Alcott’s current size.

Although the district has proposed a merger, most Alcott staff and parents don’t see it that way; they say their students would flounder in a larger school environment. And they worry that their special education students, who may not be able to attend Gallagher next year due to space constraints, are an afterthought in the district’s plans. As they grapple with decisions about where their kids will attend school next year they also ask: How do I talk to my children about this?

Salazar and the other parents had worried their school might be shuttered but didn’t want to believe it.

Adam Baggerman, Jonathan Salazar and Frank Gangale clap after a speaker gives public comment at a school board meeting on Wednesday, Nov. 19, 2025. Credit: Franziska Wild

Alcott, which is in the Edgewater neighborhood, is the only public K-5 school in the city. It has an enrollment of 167 students, and its building can’t hold more than 300 students. The district’s goal for enrollment at K-8 schools is 450 students, a number they say is necessary to offer more programs and run cost-efficient schools. Next year at Gallagher, the projected enrollment would be near 1,000 students.

At a meeting for Alcott families after the plan was proposed, parents asked why Alcott was chosen in particular. A CMSD administrator said the district mostly looked at two things: student enrollment numbers and the condition and size of the building.

One of the reasons parents want to fight for Alcott, its intimate family setting, is what puts it at risk for closure.

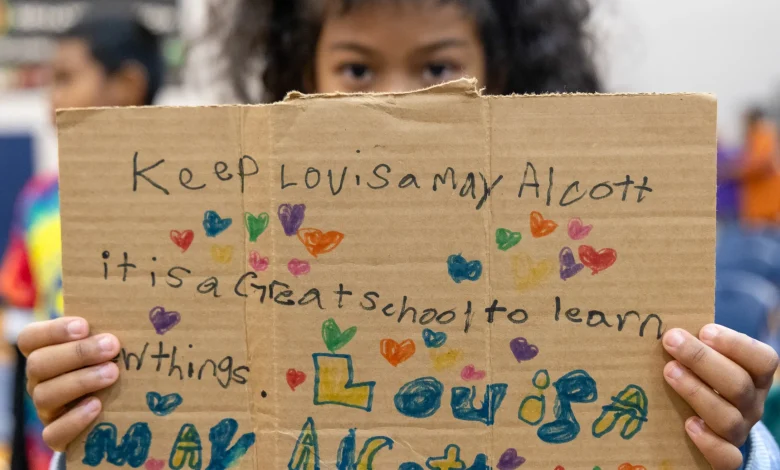

Together, families, teachers and staff have drafted a petition that has garnered hundreds of signatures. One teacher told Signal she has emailed every member of the school board multiple times. And Salazar wasn’t the only parent to show up at a school board meeting. Parents have brought their children with handmade signs in support of Alcott.

Why Alcott feels ‘right’

Salazar moved to Cleveland from New York three and a half years ago. At the time, he worried about finding a school that was the right fit for his twin boys, Xavier and Gabriel. They have autism, and Gabriel has cerebral palsy. Their dad knew not every school community was equipped to care for them.

At Alcott he found an environment that met their needs: small classes, supportive special education teachers and a community where everyone was dedicated to including his sons.

He remembers that, at one of the first parent events he attended, Gabriel ran out of the school’s gate toward the road. Salazar was too far away to reach him, but another parent saw him.

“My son is fast. He was able to catch him. He brought him back,” Salazar said. “And I was like: this is a sign, this is the spot right here.”

He credits a lot of the twins’ growth to the teachers and staff who’ve helped them over the years. Xavier started in a self-contained classroom, one where a teacher works with a handful of only special education students. Now, with the help of teachers, paraprofessionals and Alcott’s principal, Xavier has transitioned to a general education classroom.

There’s no doubt in Salazar’s mind this would not have been possible in a larger school — where staff don’t know every child individually or work to cultivate the same culture of inclusion.

Mayouri Inthavong picks up her children Maximus and Mayleigh Johnson from school at Louisa May Alcott on Monday, Nov. 24, 2025. Credit: Michael Indriolo/Signal Cleveland/CatchLight Local

Mayouri Inthavong helps her son Maximus Johnson into the car after school at Louisa May Alcott on Monday, Nov. 24, 2025. Credit: Michael Indriolo/Signal Cleveland/CatchLight Local

Mayouri Inthavong was also nervous about transitioning her two children from preschool to elementary school. But, like Salazar, the community she found at Alcott put any fears to rest. Her fourth and third grader have fit into Alcott’s community well.

With the possibility of closure, her worries are back, along with a sense of grief about losing the community that Alcott has.

“This is their second year, to hear — I’m kind of emotional — to hear that this school might close, ” she said, choking up. “It’s really, really sad, because they have a great staff here.”

Adam and Brandi Baggerman moved from Texas in the middle of last school year and enrolled their son Ryan at Alcott.

“I love that it’s smaller,” Brandi said. “I did not realize when we moved to Cleveland that schools were K-8, which made me very nervous, because Ryan’s very quiet.”

She, like Salazar, gave public comment at a November school board meeting, taking time to underscore what makes Alcott special in her eyes. The individualized attention for her son, its family feel and wraparound services like a “care closet” — are things that cannot be measured in enrollment numbers. She thinks Alcott, as the only K-5 school in the district, should be considered a speciality school and preserved.

Ceramics made by Alcott students displayed at a family meeting about the Alcott merger on Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. Credit: Franziska Wild.

Watching as she spoke were members of the Alcott community, including Frank Gangale. He sat next to Adam Baggerman and Salazar the entire meeting, all three of them wearing Alcott blue.

Gangale has lived across the street from Alcott for over 50 years, and he helps decorate the school for every holiday. For the last 12 years, he’s cooked and served lunch at Alcott.

He’s also Alcott’s unofficial grandpa. The students all have their own nicknames for him, and it’s not uncommon to watch them ambush him with a hug in the hallways.

“The people, the teachers and everybody, the staff, is all friendly. I hear horror stories from different schools where they don’t even talk to each other,” Gangle said. “We’re like family here.”

Frank Gangale, who’s worked at Alcott for 12 years, fist bumps Ryan Baggerman before a school board meeting on Wednesday, Nov. 19, 2025. Credit: Franziska Wild.

‘The false pretense that this is a merger’: Alcott’s most vulnerable students might get left behind

When presenting the merger plan in early November, CMSD CEO Warren Morgan said that the district had listened to parents and the community and attempted to prioritize mergers over closures.

But for the Alcott community, the merger feels more like a closure. They would have to move buildings and leave a neighborhood that hosts many of their field trips and where neighbors regularly volunteer at the school.

“They’re trying to make it sound like we’re not closing schools, because, to me, merging is just like we’re going to have our own operations within the same campus,” Brandi Baggerman said. “But that’s not what’s happening. I mean, at least that’s not what it looks like.”

Then, there are lingering questions about whether special education students, who make up nearly a third of Alcott’s community, will be able to join their peers at Gallagher next year.

“But why does Alcott not get to make this merger with the staff that they know? My kids are the most impacted by transitions and change. It’s the special education students who are always thought of last.”

Mary Adler, a special education teacher who’s been teaching at Louisa May Alcott for 25 years.

Mary Adler, who teaches special education students at Alcott, is particularly concerned about this possibility.

She’s been teaching at the school for 25 years and sent her own kids there. In her eyes, Alcott is unique in how fully it includes its highest need students, even modifying extracurriculars such as art club and Boy Scouts to allow them to participate.

Recently, CMSD had her send a letter home to the families she teaches, which, while guaranteeing that her students would receive the same services next year, didn’t guarantee they’d join their peers at Gallagher.

She said the district has told her Gallagher might not have the space to accommodate more special education classes. At the same CMSD board meeting where Salazar spoke, Morgan said that students receiving special education services might have to make alternative choices for school next year.

“But why does Alcott not get to make this merger with the staff that they know? My kids are the most impacted by transitions and change,” Adler said. “It’s the special education students who are always thought of last.”

Trevor Hunt has seen his daughter, who has special needs and is in the first grade at Alcott, “make great strides” in part because of the school’s small class sizes and intimacy.

His unease about next year stems from the feeling that CMSD isn’t being forthcoming with information about special education but also that Gallagher, at 900 students or more, will just be too big for his daughter.

“There seems kind of like an overwhelming number to have in that one specific school building,” he said. “I get that they’re trying to consolidate and have larger schools. That’s part of their plan. But I think what gets kind of lost in the sauce here is that there are specific needs for some students.”

‘Did we do it? Did we save my school?’

For Alcott parents, one of the hardest parts so far — in addition to trying to plan for next year — has been trying to talk to their children about what might happen to Alcott.

Salazar’s worries that Gabriel and Xavier would regress at Gallagher have prompted him to consider moving back to New York. He’s also broached the subject of Alcott closing with his sons. They know that things might change next year, and that’s been scary for them, he said.

“And, of course, I’m going to do the dad thing and tell him it’ll be OK,” he said. But, Salazar admitted, “I’m scared too.”

Hunt and his wife haven’t yet had the conversation with their daughter. She’s pretty young, and they want to wait until the board votes on Dec. 9 to try and talk about it.

They have begun to consider what they would do if Alcott closes. For their family, leaving CMSD entirely is “a realistic possibility,” according to Hunt.

That’s something Rachel Kolecky, who’s taught at Alcott for 17 years, has been hearing a lot lately. Most of the families she’s talked to have considered leaving the district, for other options like private, religious or charter schools, should Alcott close.

“Everyone I talk to, everyone,” she said, as she, along with Adler, Gangale and a few other staff, gathered in an open classroom to vent their worries about next year.

Adam Baggerman reads material about Building Brighter Futures at a family meeting about the merger at Louisa May Alcott on Thursday, Nov. 13, 2025. Credit: Franziska Wild

Brandi and Adam Baggerman are among the families considering other options, including private schools, but it’s not a choice they want to make. They have also begun the difficult process of talking to Ryan about the possibility that next year might look very different.

Having those conversations, though, is challenging in part because they don’t always answer the questions that matter most to him, like if he’ll get to see his favorite teachers next year or if his friends will come with. It isn’t even certain, yet, that Alcott will close.

“One thing that broke my heart is at the meeting that we had last week,” Brandi said. “[Ryan’s] listening, he’s engaged, and he got a little bored, and he got a little hyper by the end of it, and we adjourned, and everybody’s getting up, and he was like: ‘Did we do it? Did we save my school?’”