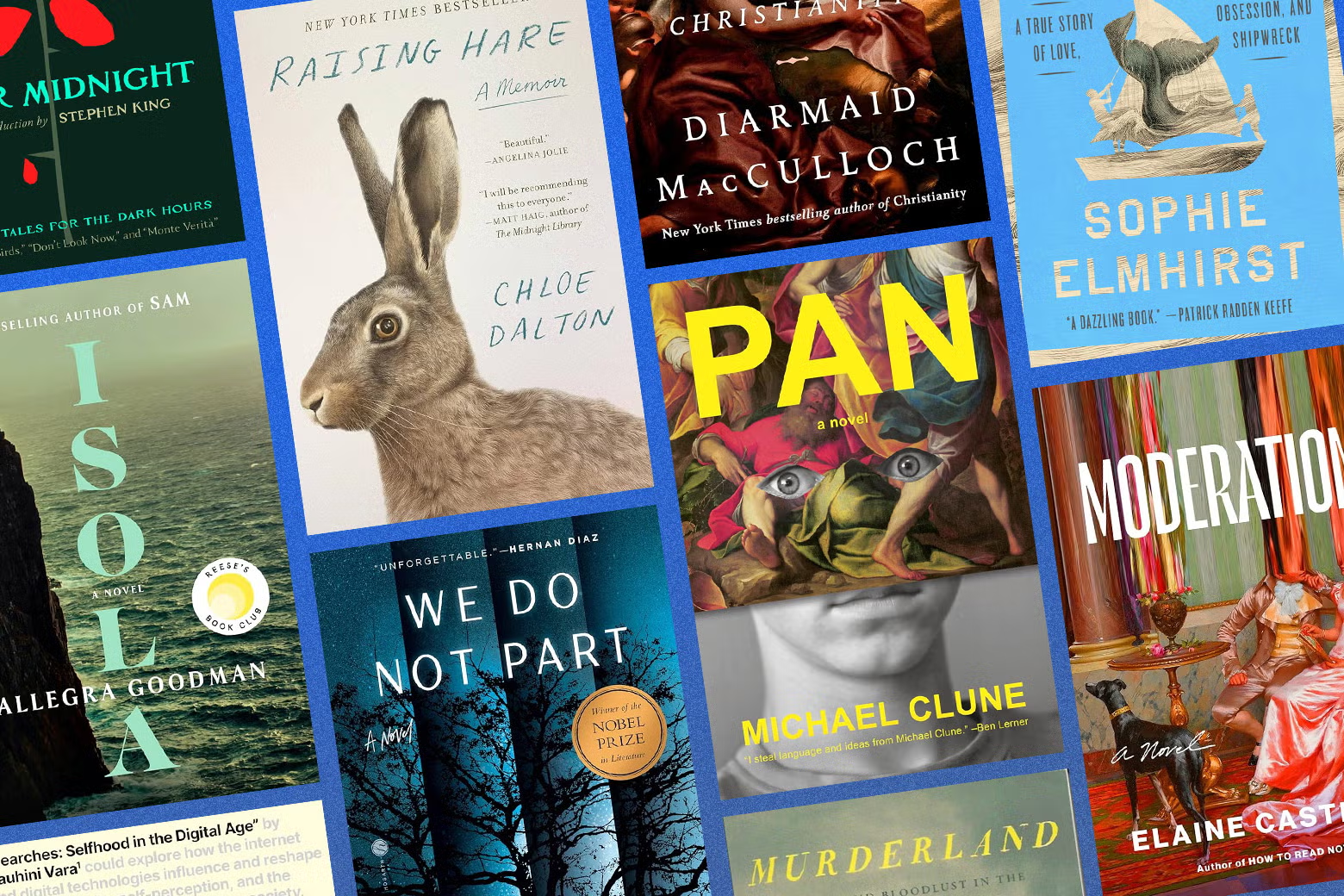

The 10 Best Books of 2025 Across Fiction and Nonfiction

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page.

Thank you for your support.

In a chaotic and distressing year, books provided a respite, a chance to commune with works of coherent voice and vision. Some people find it harder to read during days overflowing with one-minute distractions and incessant notifications, but when I took the time, I was rewarded with a slightly bigger foothold in a world of decency, humanity, patience, and compassion. Here are 10 good reasons to give that a try.

Moderation by Elaine Castillo

Girlie Delmundo is the longest-lasting moderator working in the psyche-shredding salt mines of a Meta-like social media company, scrubbing feeds of horrific images of abuse and slaughter. Like many of her co-workers, she’s Filipina, and most of her salary goes to digging her extended family out of the financial hole they fell into with the 2008 recession. Tough and sardonic, Girlie is also almost reflexively filial, so when she’s offered a fabulous salary to moderate for a burgeoning VR company providing multiuser experiences of Viking raids and tours of Rome (as well as a surprisingly potent therapeutic mode), she can’t refuse. Moderation expertly weaves a lacerating examination of the tech industry (Girlie feels most at home in the VR medieval theme park because, as far as she’s concerned, feudalism never ended) into a story of exasperating familial love, centered around Girlie’s attachment to people she finds “too beautiful to look at; she loved them more than her own life; they were the most annoying people she’d ever met and she couldn’t fucking get rid of them.”

By Elaine Castillo. Viking.

Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers by Caroline Fraser

Growing up on Washington state’s Mercer Island in the 1960s and ’70s, Caroline Fraser heard a lot about the seemingly disproportionate number of serial killers prowling the Pacific Northwest at that time. Centering her examination of this phenomenon on Ted Bundy while encompassing such figures as Gary Ridgeway (aka the Green River Killer), Fraser seeks a historical context for these freakish crimes. She identifies poisoning by lead and other heavy metals—from both leaded gas and smelting facilities in and around the Tacoma area—as a likely factor, noting that lead has been shown to increase impulsivity, aggression, and the propensity toward violence, particularly in young men. She marvels over a government map that tells her exactly how much lead and arsenic Bundy’s childhood home was exposed to and finds disturbing links between Tacoma and both Charles Manson and the D.C. sniper. All this Fraser views as the unanticipated consequences of our too-willing acceptance of the downsides of industries that bring wealth and local jobs. Fraser never loses sight of the larger picture in this beautifully written book—a rare quality in true crime. Read the author interview in Slate.

By Caroline Fraser. Penguin Press.

Pan by Michael Clune

Adolescence and madness have a lot in common, as Nick, the narrator of Michael Clune’s highly original debut novel, illustrates. Struck by random panic attacks at age 15, Nick suddenly sees himself and everything around him in dramatically different ways: His own hand becomes simply a “thing,” and “diabetes” manifests as “a word of dark magic, of poisoned time.” Even in his unpanicked state, though, Nick encounters wonders and mystery everywhere, from the unopenable decorative gate in the condominium complex where his father lives, to the music of Bach (“like math class for feelings”) and even Boston’s “More Than a Feeling,” over which he bonds with his crush, a girl who agrees that there’s “a door, right in the middle of the song, like the door on a UFO.” The two of them, along with Nick’s trickster best friend, fall in with a pair of older brothers who hang out in an old barn, drop acid, and cook up a sort of cult based on the idea that Nick’s panic attacks are visitations from the Greek god Pan (after whom panic was named). Every other sentence in this brilliant novel has a door in it, one that can take you to a whole new world, which is really this world, transfigured.

By Michael Clune. Penguin Press.

Lower Than the Angels: A History of Sex and Christianity by Diarmaid MacCulloch

Perhaps the foremost living historian of Christianity, Diarmaid MacCulloch offers a lively, insightful history of the religion’s fraught relationship with sexuality in all its forms, from same-sex desires to the role of women in the church. There’s something that will fascinate anyone interested in faith and human desire on every page of this learned but never stodgy history, from the roots of the belief that virginity brought a person closer to God to how the agricultural advances in northern Europe in the 18th century indirectly led to homosexual identity as we understand it today. Lower Than the Angels teems with fascinating characters, including a second-century Alexandrian who rejected marriage as “a confidence trick designed to protect property rights” and advocated for “communal sexual activity,” and another early Christian who petitioned church authorities for permission to castrate himself. As MacCulloch points out, there’s no bedrock Christian theology of sex, and devotees can find scriptural justifications for vastly differing positions on the topic. Humane and witty, he makes the ideal guide to this long history of contradictions and confusions. Read the review in Slate.

By Diarmaid MacCulloch. Viking.

After Midnight by Daphne du Maurier

This new collection of the late British author’s stories (with an introduction by Stephen King) demonstrates that du Maurier had more than just one indelible novel, Rebecca, in her. Even those aware that two great films—The Birds and Don’t Look Now—were based on du Maurier stories (both included here) will find more luminous gems in After Midnight, including “The Alibi,” in which a civil servant’s spontaneous plan to murder a stranger gets derailed by his adoption of an entirely new identity, and “Monte Verità,” in which a man’s fiancée vanishes into a mountain fortress inhabited by an austere, genderless, moon-worshipping sect. Best of all is “The Pool,” about the transformation of a girl’s summer idyll at her grandparents’ country house into an episode of devastating loss. Du Maurier could conjure atmospheres both gothic and Edenic out of the simplest sentences (“Last night, I dreamt I went to Manderley again”), in part because her own life was filled with a wild, restless yearning, indelibly captured by these tales. Read the review in Slate.

By Daphne du Maurier. Scribner.

Searches: Selfhood in the Digital Age by Vauhini Vara

How to describe growing up digital? It’s both a universal experience these days and highly individualized, shaped, as our internet usage is, by our own personal desires. Vauhini Vara—born in 1982—understands that desire is at the heart of our personal experience of the internet, and so in this essay collection she presents the occasional chapter that consists of nothing but questions from her own search history. These include queries ranging from “What is internet hippo?” to requests for information about the rare cancer that killed her sister in the years before the young Vara was able to look anything up online. Some of the wants driving the internet are eternal (“How to be more beautiful?” is one of Vara’s persistent concerns, as she endearingly confesses), while others are unique to those who have made their fortunes off the online vehicles where we conduct our quests. A business and technology journalist turned novelist (her The Immortal King Rao was a finalist for the 2023 Pulitzer Prize), Vara braids an account of the internet as industry into a more intimate portrait of its effect on her own life. And then she asks the most salient question of all: Whose desires will the internet ultimately reflect—ours or theirs?

By Vauhini Vara. Pantheon.

Isola by Allegra Goodman

Based on the true story of a 16th-century French noblewoman who was marooned on a desert island in New France (now Canada), Allegra Goodman’s captivating eighth novel follows its narrator from a life of luxury in which she has no liberty to a state of total freedom and deprivation. Orphaned from childhood, Marguerite inherits great wealth that her unscrupulous, adventuring older cousin squanders on sea voyages in a vain attempt to attain riches and “greatness.” Insisting that his ward accompany him on a quest to find the (mythical) Northwest Passage, Marguerite’s guardian becomes enraged when he learns that she’s fallen in love with his assistant, and strands the couple along with Marguerite’s loyal nurse. On the island, Marguerite and her companions struggle to survive. Refreshingly, Goodman resists modernizing her characters, remaining true to the role that faith and antiquated notions of virtue played in late medieval life. Nevertheless, Isola leaves its readers with the provocative question of which is more brutal: the lives of women and servants in premodern Europe or a Canadian winter spent in a cave fighting off polar bears. It’s a tough call.

By Allegra Goodman. The Dial Press.

A Marriage at Sea by Sophie Elmhirst

Journalist Sophie Elmhirst recounts the true story of a British couple who sold their home to live on a boat in the 1970s. Sailing to New Zealand fulfilled a longtime dream of both Maurice and Maralyn Bailey, but nine months into the trip, a sperm whale breached under the boat, sinking it and leaving the couple adrift on a raft in the Pacific, with what supplies they could salvage, for 117 days. She was chipper, he was the human equivalent of Eeyore, and while the Baileys did publish their own account of their ordeal in 1974, Elmhirst digs deeper than these somewhat unreflective survivors ever could. The pun in the title isn’t really a pun at all, but a testament to the complex and ineffable institution of marriage itself. Hers is a sensitive portrait of what brings two people together and the sometimes surprising chemistry that makes for a lasting bond. What couple doesn’t wonder how each of them would behave in extremis? Would you kill and eat a shark, then make a purse out of its shiny skin? Or would you simply mope? Only 117 days on a raft will tell.

By Sophie Elmhirst. Riverhead Books.

We Do Not Part by Han Kang

Han Kang’s pristine and enigmatic 11th novel is the story of two friends, Kyungha and Inseon, haunted by a massacre of civilian activists on an unnamed island—clearly based on the pro-democracy uprising in Gwangju, which was lethally repressed by the South Korean military in 1980. Kyungha, the novel’s main character, falls into a depression after writing a book about the atrocity, only rousing herself when a hospitalized Inseon asks her to rescue her pet parakeet from dying of thirst. To do so, however, Kyungha must make her way through a blizzard to the mountain cabin where her friend has been working on the eerie sculptures they have envisioned as a monument to the dead. Neither woman has any direct experience of the massacre, which occurred during their mothers’ youth, yet the human capacity for both cruelty and suffering (a frequent theme in Han’s fiction) threatens to overwhelm them. Kyungha’s journey to save one small life becomes a quest to receive and to honor the memories of the lost. Read the review in Slate.

Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton

-

The Sexy Hockey Show People Are Going Wild for Really Is That Hot

A hard-charging political consultant and speechwriter when the pandemic hit, Chloe Dalton found herself holed up alone in the old stone farmhouse she’d been restoring as a hobby. One day, investigating a dog’s bark, she encounters a leveret, or baby hare, on a trail. After leaving it for the day in case its mother showed up, Dalton finally decides to take the leveret in before the frigid night descends. She nurses the animal with kitten formula and scrupulously encourages it to go outside when it’s ready. The hare becomes less a pet than a housemate, a shy and elegant wild thing with whom Dalton forms a precious bond. A gifted writer, she describes the hare in great detail and with great tenderness, clearly a product of observing it very closely. She even learns to communicate with the animal via sounds and gestures. The hare comes and goes as it pleases, and Dalton adjusts to the fact that someday it will never return. The two creatures enter into a dreamlike companionship so nourishing to Dalton that she almost doesn’t care when the hare chews through both her router and TV cables. That’s love.

By Chloe Dalton. Pantheon.

Read more about the best of 2025.