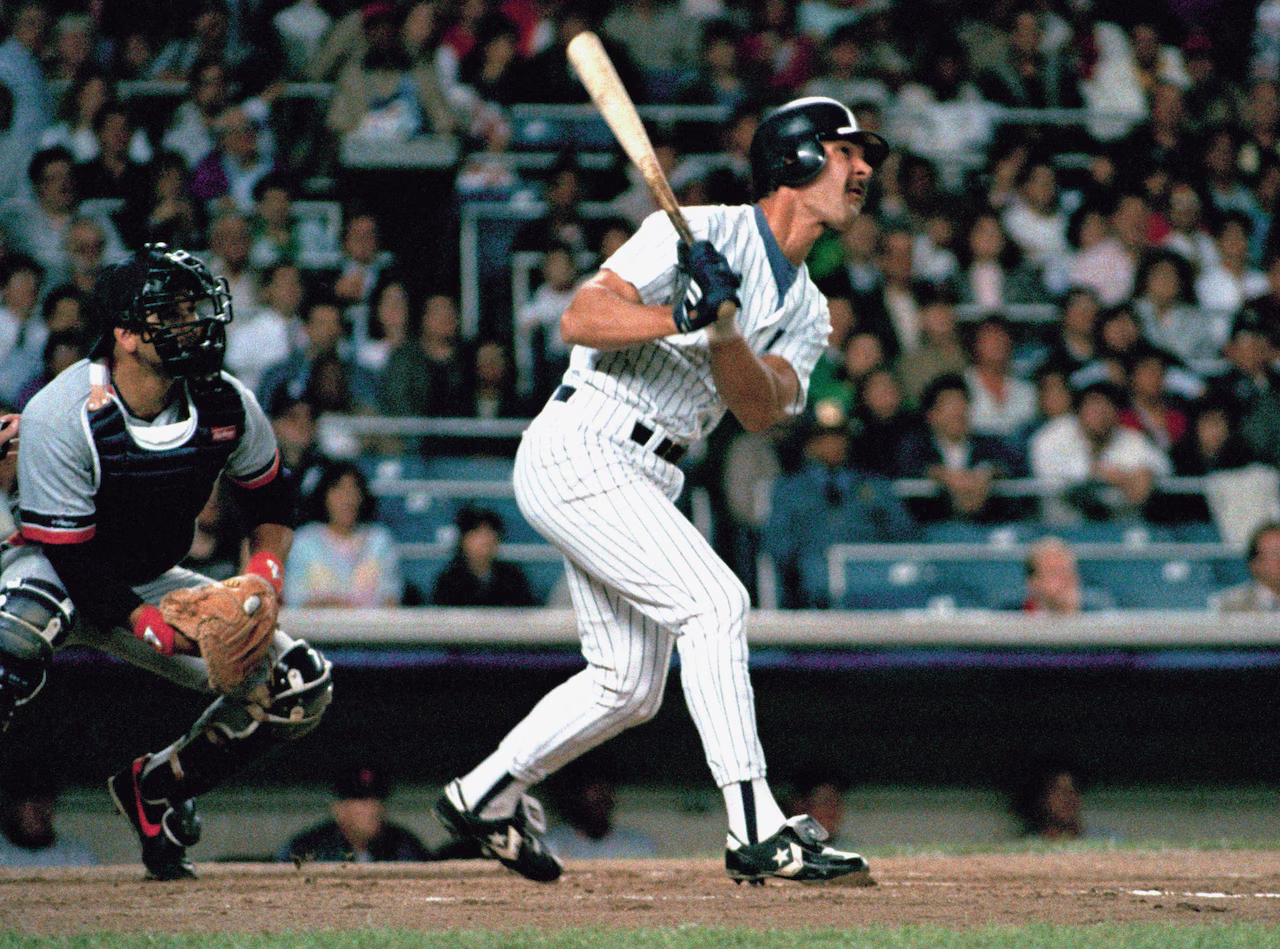

Yankees legend Don Mattingly has waited long enough for Cooperstown | Klapisch

One of Don Mattingly’s most endearing qualities is his no-bling personality, which is to say, he’s a rare breed these days. He’s confident without being arrogant, smart without smugness.

So good luck trying to get Mattingly to promote himself for the Hall of Fame. It’ll never happen. The former Yankees captain will let the numbers sell his candidacy, even if that didn’t work out the first time around.

Mattingly hasn’t appeared on a general Cooperstown ballot since 2015, when he was cycled out of the election process. His case was considered over a 15-year span and never once exceeded 28.2%.

There was a reprieve of sorts in 2022, when the 16-member contemporary era committee added Mattingly’s name to the ballot. But again, he ran into hard luck, falling four votes shy.

There’s another contemporary era committee election this weekend. I think Mattingly has a legitimate chance. Maybe it’s because it’s a fresh ballot with new candidates and new voters (they rotate every four years).

Or maybe it’s just me.

I admit to having a soft spot for Mattingly, having covered him in his prime. He, along with Mets legend Keith Hernandez, represented a golden era in New York, at least for first basemen. I can’t think of one without the other. More on that later.

I’m certainly not oblivious to the roadblocks Mattingly has faced. His most productive window closed before he turned 30. If your career is that short, you better have a resume that resembles Sandy Koufax’s. And Mattingly left the game without a ring. That doesn’t help his cause, either.

Still, Mattingly retired with a batting title and an MVP award to his name. And he was one of the industry’s best players in the mid-to-late 80s. Where is it written that career brevity is an automatic disqualifier?

Perhaps this voting bloc will see Mattingly with fresh eyes. Perspectives do change. It’s why players are given 10 election cycles (it used to be 15). It’s why some generational stars win in a landslide in Year One. Others have to sweat it out for the entire decade.

And let’s face it, these contests are often about popularity. The rules specifically ask voters to consider the morals clause. Meaning, good guys get a wider berth.

And as Mattingly ages, (he’ll turn 65 in April), the wiser he becomes. In fact, plenty of Yankees fans have asked me why Mattingly hasn’t been hired in the Bronx, at least to serve as Aaron Boone’s bench coach.

It’s not for a lack of knowledge. The front office has nothing but respect for Mattingly. But Boone is their guy, which would make it difficult to make Mattingly his No. 2. The perception that Mattingly was waiting for Boone to get fired is enough to quash the idea.

Not that I agree with it. Mattingly has no ego about such things. In 2017, the first year Derek Jeter joined the Marlins’ ownership group, he met privately with Mattingly, who was already their manager.

What could’ve been an awkward conversation – two former Yankees captains, the most popular players of their respective eras – was instantly defused by Mattingly.

“I told Jete from the get-go, ‘You’re not going to have any problems with me,’“ Mattingly recalled last year. “‘You’re the boss here, I work for you. Whatever you want to do is fine with me.’“

But it’s not the relationship with Jeter that interested me the most about Mattingly. It was the world in which he co-existed with Hernandez.

Mattingly was the superior hitter; he certainly had more power. Hernandez, an 11-time Gold Glove winner, was the more gifted defender with the stronger throwing arm.

No one was better at cutting down runners trying to advance to third on a sacrifice bunt. But overall, it’s amazing how similar their careers were.

Mattingly had a lifetime OPS of .859, Hernandez’s was .820, although that metric doesn’t fairly weigh on-base percentage. Mattingly topped Hernandez in slugging percentage (.471 to .436), but Hernandez was on base more often.

Why? Because of his sharp eye and uncanny discipline. Mattingly drew 588 walks in his career; Hernandez drew 1070. That’s a difference of 522 extra times on base in only 860 more plate appearances.

The difference is even more stark considering their respective personalities. Mattingly was a billboard of calm; he still is. His demeanor was what the Yankees’ clubhouse needed in those fiery times when late owner George Steinbrenner shuffled managers in and out of the room like cattle.

Hernandez’s clock was wound tighter. He was a more ferocious player, and person, than Mattingly. That’s not to say he was more talented, simply more volatile.

In many ways, Hernandez was the embodiment of the 80s-era Mets themselves – wild, to say the least.

I would open the Cooperstown door for both Hernandez and Mattingly if I were in a position to do so. Even though I’m a Hall of Fame voter, I’m not one of the writers picked for the legacy elections. All I’ve got is my keyboard and a strong opinion.

That and a unique appreciation for Mattingly’s competitive flame.

I once asked Donnie Baseball about the last time he stepped in a batter’s box.

“Last game (in the American League Division Series) in ’95,” Mattingly said. “Why?”

“Because I’m still pitching in a semi-pro league in Jersey,” I said. “I think I could get you out at this point.”

I was hoping Mattingly would take the bait, which of course he did.

Eyes narrowing, Mattingly said, “Klap, I could be 90, and I’d still rake you.”

It took Mattingly a moment to realize I was kidding. But he wasn’t.

Bless him.