Before murder case, Brian Walshe was accused of draining his father’s bank accounts, making off with more than $500,000

According to a copy of his will that was later accepted by the court, Thomas Walshe acknowledged he had “only one child Brian Reza Walshe with whom I am not in contact.”

“If I do not herewith bequeath property in this will to Brian Reza Walshe . . . my failure to do so is intentional,” the father wrote. “I hereby bequeath to Brian R. Walshe my best wishes but nothing else from my estate.”

Get Starting Point

Back in December 2018, however, Brian Walshe had argued that his father left no will, convincing the court to appoint him personal representative to the estate.

With that authority, he began liquidating his father’s assets.

According to documents filed in the probate case, however, the older man’s friends and nephew later stepped in, accusing Walshe of secretly destroying his father’s will for his own personal gain. They argued he drained his father’s bank accounts and sold off his belongings — estimated to total more than $500,000 — while also seeking to sell his father’s home in Hull.

“Brian and Tom’s estrangement had everything to do with money,” the elder Walshe’s longtime friend, Fred Pescatore, told the court in a signed statement. “Brian stole money from Tom and swindled him out of almost one million dollars” during his life.

Hauntingly, Pescatore went on to allege Brian Walshe had a violent streak, describing him as “very angry” and a “sociopath.”

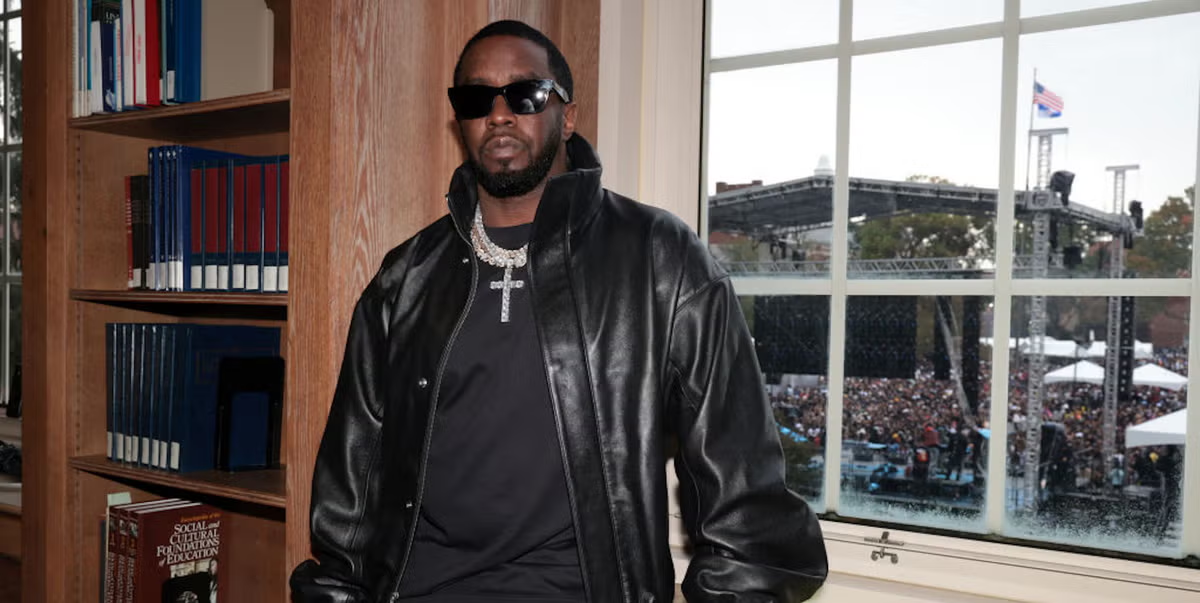

The case, which played out alongside Walshe’s criminal art fraud trial, was one of several legal and financial entanglements Walshe faced in the years before he was accused of killing his wife, Ana, on Jan. 1, 2023. Walshe, 50, is now on trial in Norfolk Superior Court for Ana Walshe’s murder, where prosecutors allege he cut up her body and dumped her remains.

Walshe has denied the murder charge, though he’s admitted moving the body and lying about it to police.

Walshe’s attorney in the probate case, Anthony Porcello, did not respond to a request for comment.

By the time Walshe’s father died in September 2018, the father and son had had “almost zero contact” for more than a decade, according to accounts filed in the probate case.

Nevertheless, as news of his father’s death began to circulate, Walshe allegedly contacted Jeffrey Ornstein, his father’s longtime friend who’d helped renovate the older man’s house in Hull.

“Brian texted me and asked if I had keys or access to the Hull House, as he needed some paperwork,” Ornstein said in a signed statement submitted to the court.

Ornstein added that when he entered the house to find the documents and get Walshe a set of keys, he noticed Thomas Walshe’s will on a cabinet in the office.

“I reviewed the Will and left it where we found it, however, I took some pictures,” Ornstein told the court. “I noticed a list of beneficiaries, but as Tom had told me many times over the years, he had expressly disinherited Brian.”

In addition to disinheriting his son, Ornstein continued, Thomas Walshe’s will named his nephew, Andrew Walshe, as executor.

“I still felt bad,” Ornstein continued, “so when I texted Brian later that day to tell him that I had left him a set of keys under the mat, I did not tell him about being disinherited.”

According to court documents, the rift between father and son stemmed from an alleged theft of nearly $1 million.

The dispute arose after Brian Walshe acquired a tumbledown home in Lenox in the early 2000s, according to previous Globe reporting. His father allegedly agreed to fund renovations, with the idea that his son would pay him back the original amount and keep any profits once the home sold.

But instead of paying his father back, Walshe pocketed the money and disappeared, according to a longtime friend of the father.

“Tom said he talked to Brian that day; he was going to the bank,” said the friend, who requested anonymity. “That was the last time Tom heard from Brian in 10 years.”

Nevertheless, Walshe got himself named personal representative for his father’s estate in December 2018. According to court documents, Walshe did not inform any of his father’s other relatives of the death.

Meanwhile, the elder Walshe’s nephew, Andrew Walshe, told the probate court he had become increasingly anxious that winter when his uncle didn’t reply to numerous messages.

Andrew Walshe did not respond to Globe interview requests. He told the court, however, that he eventually contacted his uncle’s friends, who told him Thomas Walshe had died.

By then, Pescatore was preparing to seek a restraining order to block Brian Walshe’s bid to sell his father’s house in Hull. He told Andrew Walshe that although his uncle had left a will naming him executor, Brian Walshe had control of the estate. What’s more: His cousin had already removed valuables from the house in Hull.

Andrew Walshe, who said he’d agreed to serve as executor roughly 10 years earlier, asked the court in July 2019 to remove his cousin and appoint him as personal representative for his uncle’s estate.

“It is clear that Brian destroyed the Last Will and Testament which excluded him from any inheritance, when he gained access to the Hull property,” Andrew Walshe wrote in a signed statement.

Separately, he added that Brian Walshe hadn’t contacted family members — many named as beneficiaries — about his uncle’s death.

“Brian R Walshe had estranged himself from all Walshe family members due to their knowledge of the theft he had committed to his father,” Andrew Walshe told the court. “Had any members of the Walshe family been informed, questions would have been raised much earlier regarding the estate.”

To support his claim, the nephew submitted photos Ornstein had taken of the will as well as signed statements from two of his uncle’s friends who’d acted as witnesses to the will, dated May 1, 2016.

Brian Walshe sought to fight off his cousin’s claim. He told the court he and his father had reconciled in March 2017, adding they were planning for the elder Walshe to move in with him and Ana as the older man’s needs changed.

It “was the first time we had spoken candidly since a family therapy session in 1996,” Walshe wrote in a signed statement to the court. He suggested their schism stemmed from his father’s “alternative lifestyle” following the divorce, adding that after his father suffered a stroke in early 2016 it “would have been medically impossible for him to write a will by himself, much less sign it.”

“The signature is a possible forgery,” he suggested.

Thomas Walshe’s longtime friend Fred Pescatore declined a Globe interview request. In court, however, he characterized Brian Walshe’s version of events as a “pack of lies.”

“Their estrangement had nothing to do with Tom’s ‘alternative lifestyle’ but rather all to do with Brian being a sociopath,” Pescatore wrote.

He went on to describe a trip to Asia he’d taken years earlier with the father and son.

“I saw Brian attempt to smuggle out antiquities from China,” said Pescatore, characterizing the younger Walshe as a “very angry and physically violent person.” “When Brian was confronted, he picked up a stanchion and literally attempted to kill four or five guards that had come to talk to him about his crime.”

The court ultimately accepted Ornstein’s photos of the will and sided with Andrew Walshe, naming him personal representative for the estate. The nephew then spent months trying to compel Brian Walshe to provide a full accounting of how he’d administered the estate.

Andrew Walshe alleged his cousin had drained the elder Walshe’s bank accounts of at least $250,000 and sold his possessions, which he pegged at another quarter million dollars.

But after months of failed attempts to get his cousin to account for the estate, Andrew Walshe abandoned the effort in fall of 2023.

It was clear, he said, that ”Brian Walshe will not render an account.”

Malcolm Gay can be reached at malcolm.gay@globe.com. Follow him @malcolmgay.