New California Earthquake Swarms Have People on Edge About the “Big One”

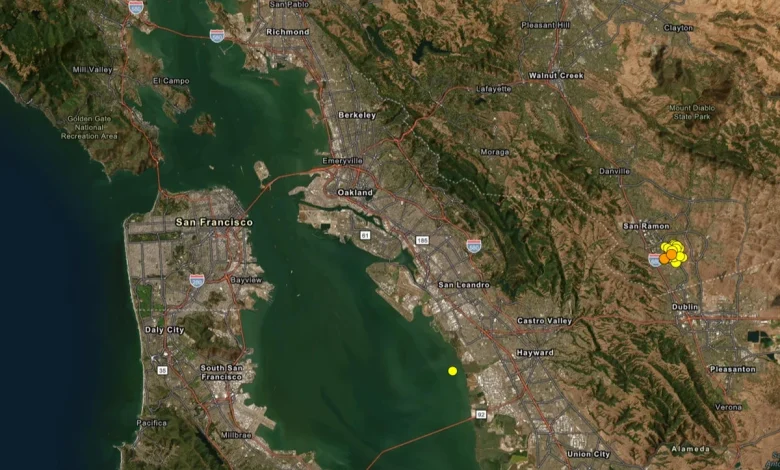

A swarm just east of San Francisco is one of two in the area getting attention from locals that think the “Big One” is coming soon. Each dot reflects the epicenter of an earthquake in the last 30 days; many are close to each other, obscuring the other dots. Image: USGS

New earthquake swarms in recent days have put some in California around the San Francisco area on edge, alarmed that the “Big One” may be coming. Recent large earthquakes in Japan and Alaska are adding to the fear that a significant earthquake could soon strike California. USGS says the odds of a larger earthquake striking are high, although those odds are over an extended period of time and not necessarily over the short-term next few days or weeks.

The “Big One” in California refers to a major earthquake, likely magnitude 7.8 or higher, expected along the San Andreas Fault, potentially causing widespread destruction, significant loss of life, and massive economic damage to California. Scientists say there is a high probability of such a large earthquake striking the state in the coming years, putting odds at 72% that a magnitude 6.7 or greater earthquake will strike the broader Bay Area between now and 2043. Unfortunately, scientists with USGS say that with modern technology and earthquake forecasting, they cannot narrow down the window to determine when such a large scale disaster will strike.

But because scientists stress it’s a matter of “when, not if”, ongoing moderate earthquake swarms near the Bay Area along with headline-generating large earthquakes elsewhere in the world have the region on edge.

While California ranks second in the US in seismic activity, most quakes are small and go largely unnoticed. That has changed in recent weeks with two swarms impacting the Bay Area: one is east of San Francisco near San Ramon; the other is north of San Francisco near The Geysers.

Over the last 30 days, USGS has reported 1,470 earthquakes around The Geysers; in just the last 7 days, there have been 286. Most of these have been weak, with only 5 earthquakes rated a magnitude 2.0 or higher intensity over the last week. While the volume has been eyebrow raising, the intensity hasn’t.

The opposite has been the case near San Ramon. There, over the last 30 days, there have been 139 earthquakes reported by USGS; over the last 7 days, that number has been 25. But the intensity of these earthquakes have been greater, with 39 rated magnitude 2.0 or greater and 6 rated 3.0 or greater over the last 30 days.

People are keeping an eye on two swarms; the orange one has more earthquakes but of lower intensity while the red area has fewer earthquakes but they are of more significant intensity. Image: USGS

According to USGS, earthquakes with a magnitude of 2.0 or less are rarely felt or heard by people, but once they exceed 2.0, as many of these events did, more and more people can feel them. While damage is possible with magnitude 3.0 events or greater, significant damage and casualties usually don’t occur until the magnitude of a seismic event rises to a 5.5 or greater rated event.

According to USGS, a swarm is a sequence of mostly small earthquakes with no identifiable mainshock. “Swarms are usually short-lived, but they can continue for days, weeks, or sometimes even months,” USGS adds.

Experts say these “seismic swarms” are not unusual. Similar patterns occurred in 2002, 2003, and 2015 along the Calaveras Fault, part of the larger San Andreas and Hayward fault system. While these smaller quakes may relieve some stress, they don’t eliminate the risk of a major event.

Volcanic arcs and oceanic trenches partly encircling the Pacific Basin form the so-called Ring of Fire, a zone of frequent earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The trenches are shown in blue-green. The volcanic island arcs, although not labelled, are parallel to, and always landward of, the trenches. For example, the island arc associated with the Aleutian Trench is represented by the long chain of volcanoes that make up the Aleutian Islands. Image; USGS

However, with other areas experiencing “big ones”, there’s concern by some that these swarms are a precursor to a big one in California. One large earthquake hit Alaska on December 6 with a magnitude of 7.0, the second, a 7.6 magnitude “mega-quake”, hit northern Japan on December 8, prompted tsunami advisories across a broad area. While not directly linked to each other, California, Alaska, and Japan earthquakes have one thing in common: they’re all located around the “Ring of Fire.”

The Ring of Fire is a string of ongoing seismic and/or volcanic activity around the edges of the Pacific Ocean. Roughly 90% of all earthquakes occur along the Ring of Fire, and the ring is dotted with 75% of all active volcanoes on Earth. The Ring of Fire is the result of plate tectonics; plates on the Earth’s surface are constantly moving atop a layer of solid and molten rock called the mantle. Sometimes these plates collide, move apart, or slide next to each other; in these areas, like the Ring of Fire, earthquake and volcano activity is abundant.