Predator: Badlands movie review (2025)

Set on one of the most dangerous planets in movie history, “Predator: Badlands” is an exceptional sci-fi action thriller with memorable characters, beautiful and terrifying animals (and plants), a structurally airtight script, and lead performances that deserve to be included in discussions of the year’s best (but likely won’t, because much of their brilliance is nonverbal). It’s a memorable entry in the Predator franchise, with enough familiar situations and high-tech hunting gear to satisfy fans of the series, but a story that stands alone. Most impressively, it’s a sincere consideration of what it means to be human, even though there are zero humans in it.

None of the above will surprise those who’ve followed recent developments in this franchise. This entry and its two predecessors, the all-Native American sci-fi Western “Prey” and the animated anthology “Predator: Killer of Killers,” were directed by Dan Trachtenberg. His takes on the Predator formula have an alchemical originality. They make sure to include situations and images that fans of the franchise have been trained to expect, but they’re so structurally, tonally, and visually distinctive that it’s impossible to say which is the best. Different but equal is more like it. They have the obsessive consistency of George A. Romero’s zombie pictures, John Woo’s Hong Kong shoot-’em-ups, Takeshi Kitano’s yakuza thrillers, all of which mined seemingly limitless supplies of inspiration from material that others had written off as unworthy of serious attention.

“Badlands” is the first Predator movie to have a Predator as its main character. The story begins on the Predators’ home world. The species is known as the Yaujta. They’re a violently aggressive culture in the vein of the Klingons, worshiping strength and loathing every manifestation of vulnerability. The main character is Dek, a young predator who wants to be officially recognized as a warrior but has been excluded from consideration due to his youth and small stature (the others call him “a runt”). After Dek narrowly escapes being killed by his own father, the chief of his tribe, he flees to Genna, also known as The Death Planet, where he aims to kill a supposedly invincible predator that has slain all other challengers and take its head and spine home to daddy.

The first section of “Predator: Badlands” is a pure survival story, about a newcomer in a treacherous wilderness who must learn about the terrain, flora, and fauna to survive and get closer to his goal. Think of a movie like “Robinson Crusoe,” “Jeremiah Johnson,” or “Cast Away,” but translated to a science fiction setting. The first part of the movie is perhaps a bit too familiar for its own good—”tribal outcast plots triumphant return” is as old as narrative itself—but it becomes fresh and exciting when Dek lands on Genna and realizes that the entire planet is determined to kill him.

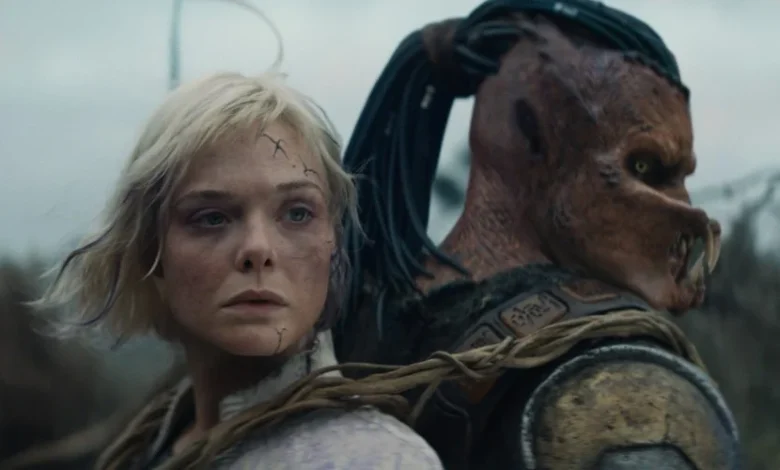

He finds an unexpected ally in Thia (Elle Fanning), an android who was part of an all-android landing party financed by the Weyland-Yutani, the galactic megacorporation behind most of the shenanigans in the Alien franchise. (Both the “Predator” and “Alien” series were owned by 20th Century Fox, now wholly owned by Disney; Fox started connecting them decades ago in “Alien vs. Predator” comics and films, but this movie merges them much more decisively.)

Like Dek, Thia came to Genna in search of a super-predator known as the Kalisk, a spiny, bristling, dagger-toothed thing that’s probably ten meters tall. As in many an Alien story, the plan was to capture one or more vicious creatures and deliver them to the company’s bioweapons division. Thia tells Dek that the Kalisk destroyed her landing party and left her for dead after ripping her in half. Now she walks on her arms in swaying movements that evoke a gymnast on parallel bars. She also says that there was another android of her make and model in their group who went by the name Tessa, and that Thia believes she’s still alive (a leap of faith that suggests Thia is already manifesting human qualities). Tessa is also played by Fanning, in a collaboration between actress and crew that’s as dazzling as Michael Fassbender’s twinned performances in “Alien Covenant.” Thia wants to return to the scene of the massacre to save Tessa and reattach herself to her missing legs, and promises to help Dek defeat the Kalisk if he’ll let her be his partner and guide.

What ensues is a wonderfully perverse twist on the buddy movie. Fanning initially plays Thia as a tragic but charming kook in the mode of Diane Keaton’s chatterbox intellectuals. She’s so relentlessly inquisitive and friendly that being around her is torture for Drek, who hates small talk and takes pride in working alone. At first Dek carries Thia’s upper half like a baby in a carrier, then changes his mind and wears her like a backpack after tiring of her constant yammering and rude questions (“What does the chewing—your outside fangs, or your inside teeth?”). But despite his annoyance, Dek won’t abandon Thia because she knows the planet and can warn him of dangers he wouldn’t otherwise recognize. “The only way to survive Genna is to learn it,” she says.

Both Dek and the movie take Thia’s advice to heart, resulting in a rare portrait of an alien world that feels as researched as documentary footage of Earth’s creatures. Trachtenberg has claimed the epic naturalist Terrence Malick as one of many directorial influences, along with Western directors like Clint Eastwood and Sergio Leone, both of whom are cleverly but subtly referenced. The Malick nod might sound absurdly lofty unless you’ve seen Trachtenberg’s previous Predator films, which have a respectful, attentive, often awed appreciation of how different species interact within an ecosystem that is as important to the story as the characters who move through it.

Many planetary exploration movies only seem interested in big, scary carnivores. This one has lots of them, all spectacular. But it’s equally interested in smaller creatures, including herbivores, insects, and plants. And it delves even deeper into world-building by showing that all of Genna’s creatures have some awareness of their fellow beings’ characteristics, and know how to evade, thwart, or simply use them to hunt or survive being hunted. This is illustrated in an early scene where a pterodactyl-like flying creature drops stones on a plant that’s covered with quivering sacs, causing them to explode and create a kind of organic napalm to injure would-be prey.

Tools are an important part of this story, as they always are in Predator movies. Dek has his own imported gear, of course, and uses it with flair. But like many a human adversary battling Predators, there are times when he’s deprived of his usual kit and has to use whatever happens to be around him to create a new thing to kill a foe before it kills him first. There are abstracted, multivalent notions of “family” floating around in the movie as well. These thankfully serve more as thought prompts than cheesy inspirational slogans. Dek and Thia’s invocation of fathers, brothers, sisters and mothers (as in the “Alien” films, the crews on company starships take orders from a master computer called MUTHER, which represents their corporate masters) convey the reflexive associations and deceptive possibilities that those words entail. The stark personality differences between Thia and Tessa (the latter is as cold as Tessa is warm, and impervious to sentiment) show how familial labels can be weaponized against those who desire love and try to think the best of others. There’s also a chattering, big-eyed, dog-faced simian called Bud who joins the duo, forming a crackpot variant of a found family. Bud, a female, mirrors Dek’s gestures and rituals like a child imitating a parent.

To its credit, “Predator: Badlands” is never content to invoke concepts like “tool,” “family,” or “weakness” and only let them drive a part of the plot or add a splash of detail to characters (though the film does both things very well). Instead, in conversations between Thia and Dek as well as in intricately mapped-out action sequences, it shows different ways that one could interpret such concepts, self-servingly or generously. Dek and Thia’s interactions expand both of their minds, opening them to new meanings and giving them permission to make choices they wouldn’t have considered otherwise. Thia never thought of Tessa as a sister until Dek suggested the term after tersely describing his brother. Dek never questioned the wisdom of sticking with his people’s warrior code until Thia caught him equating empathy, grief, and even memory with weakness. She tells Dek she was programmed to feel emotion because it improves a synthetic person’s chances of survival; instilling trust makes other beings more willing to give up useful secrets. Dek seems surprised by how sensible she sounds. Ditto when Thia tells Dek, “I could survive on my own. But why would I want to survive on my own?”

There’s much more to recommend this movie. But we won’t get into more detail here because one of the great pleasures of watching it is not quite knowing where it’s taking you, being surprised where it goes, then retrospectively appreciating how every turn in the story was telegraphed in images as well as in dialogue. Among its other satisfactions, it’s an even more coded riff on the Western than “Prey.” It might make Eastwood fans think of his early masterpiece “The Outlaw Josey Wales,” about an embittered, vengeful warrior who insists he rides alone and doesn’t want responsibility for anyone but himself, but somehow keeps accumulating allies and dependents as he goes along. At one point, Thia tells Dek about the idea of an animal pack being led by an alpha, then says that the word is widely misunderstood and misapplied. The true alpha, she says, is not the toughest, meanest, most violent creature in a group, but the one that does the best job of leading and protecting the rest.

In the end, “Predator: Badlands” is a bizarrely inspirational adventure about different types of beings overcoming the limiting parts of their own programming (literal or figurative) and/or proving that there is more to them than others assumed. The takeaway is applicable to beings all across the universe: sometimes the things you want most are not worth having, and when you figure that out, you’ll be free.