South Africa’s role in DRC peace efforts fades

South Africa has withdrawn from the DRC peace mission, as regional fractures deepen. The U.S.-led deal highlights resource-driven geopolitics.

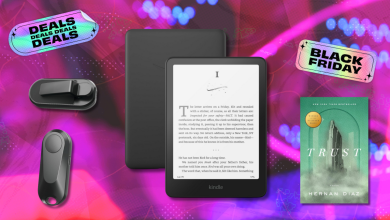

Feb. 13, Pretoria: President Cyril Ramaphosa (center) attends a ceremony repatriating the remains of South African soldiers killed by M23 rebels in DRC. The troops were part of a Southern African peacekeeping mission. © Getty Images

×

In a nutshell

- Resource extraction in DRC fuels the underlying conflict cycle

- South Africa’s military retreat undermines its regional influence

- The U.S.-led peace deal ties security to mineral access

- For comprehensive insights, tune into our AI-powered podcast here

South Africa’s efforts to broker a peace deal in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) have become increasingly precarious, mirroring the broader African continent’s struggle to assert leadership in one of its longest-running and deadliest crises. Nearly three decades of violence have claimed an estimated 6 million lives and displaced over 7 million people, as of late 2025. Fueled by over 100 armed groups and proxy wars involving Rwanda and Uganda, the DRC conflict remains a crucible of regional instability.

Over the past 20 years, numerous nations, including Angola, Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, South Africa, South Sudan, Uganda and Zimbabwe, have become enmeshed in the DRC crisis, albeit to varying degrees. Many have encountered setbacks and unpredictable developments that have led to reevaluations of their commitment and, in some cases, withdrawal.

While there were high hopes for regional cooperation, the DRC conflict has instead revealed deep divisions among African nations. Contrasting national interests have hampered a unified response. Tensions between South Africa and Rwanda have risen, underscoring the difficulties that African nations face in coming together to address the turmoil in DRC.

×

Facts & figures

Timeline of the DRC conflict

1994: Rwandan genocide.

1996-1997: First Congo War.

1998-2002: Second Congo War.

1999: South Africa participates diplomatically in the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement, aimed at ending the Second Congo War. The ceasefire collapses.

1999-present: United Nations peacekeeping mission to DRC is established.

2001: President Laurent Kabila is assassinated by his bodyguard; his son, Joseph Kabila, succeeds him.

2006: Free elections are held for the first time in four decades; Joseph Kabila wins.

2012-2013: M23 becomes a major armed force in eastern DRC.

2013: South Africa joins the UN’s Force Intervention Brigade, alongside Tanzania and Malawi.

2018: Felix Tshisekedi is elected president.

2022: M23 reemerges after five years of inactivity. The rebel group launches a major offensive in March.

2022-2023: The East African Community (EAC) deploys a regional force under the “Nairobi Process” ceasefire agreement, which ultimately failed.

2023–2025: The Southern African Development Community deploys the SAMIDRC mission to support the DRC government, with South Africa contributing the largest contingent of troops.

2023: M23 rebels seize large parts of North Kivu province.

January 2025: M23 captures the city of Goma.

June 2025: Foreign ministers of Rwanda and DRC sign a peace treaty in Washington, D.C.

July 2025: Former President Kabila is prosecuted in absentia for alleged support of M23 and Congo River Alliance (or AFC) and is sentenced to death.

November 2025: M23 and the DRC government sign a peace framework in Qatar.

This timeline highlights key events in the DRC conflict and is not exhaustive.

M23’s January offensive: The tipping point

In January, M23 rebels – reported by the UN to be receiving military support from Rwanda – captured several towns in the Kivu region, including Goma, the economic and logistical heart of eastern DRC. During the offensive, 14 South African National Defence Force (SANDF) soldiers were killed in clashes and ambushes, marking the largest military death toll for the country in the post-apartheid era.

The deaths sparked immediate diplomatic turmoil: South African President Cyril Ramaphosa publicly accused the Rwanda Defence Force of involvement, which led to a heated response from Rwandan President Paul Kagame. He labeled the Southern African Development Community Mission in the DRC (SAMIDRC) as a “belligerent force” and issued a stern warning about potential confrontation.

In March, President Ramaphosa and other Southern African leaders announced the end of the SAMIDRC and a phased withdrawal of troops. The pullout began in late April, leaving DRC President Felix Tshisekedi’s government diplomatically isolated and militarily vulnerable as M23 solidified control over key mining routes in North and South Kivu.

Rwanda has adopted an increasingly hardline position, asserting that any peace agreement in DRC requires substantial involvement from Kigali. Rwanda has faced international condemnation for supporting the M23 rebel group; however, it has pushed back by highlighting longstanding border disputes. It argues that ethnic Rwandans who found themselves on the DRC side due to colonial-era borders continue to endure severe persecution and, in some instances, ethnic cleansing perpetrated by DRC authorities. These roots run deep, and reopen the scars of the Tutsi-Hutu conflicts in the region that exploded into the 1994 genocide. What began as a brutal historical feud has since evolved into a high-stakes geopolitical battle over DRC’s immense mineral wealth.

×

Facts & figures

Territory controlled by M23 in eastern DRC

South Africa’s engagement in DRC

In the early 2000s, South Africa began engaging with DRC through the Southern African Development Community (SADC), taking part in regional initiatives aimed at fostering peace and stability. Through SADC-led efforts and South Africa’s diplomatic initiatives, DRC held its first democratic elections in 2006.

Initially, South Africa’s diplomatic involvement in DRC was driven by a sense of moral responsibility, significantly enhanced by the newfound legitimacy of its government following the country’s transition to democracy. This approach aligned well with the ideals of a post-apartheid foreign policy, and South Africa’s role was widely viewed as principled, especially when contrasted with the resource exploitation by other regional players. South Africa contributed the largest contingent of troops to the SAMIDRC.

However, recent developments marked by M23’s advance in eastern DRC and the total collapse of the peace process, raise difficult questions about the rationale behind South Africa’s involvement in the first place. The abrupt withdrawal of South Africa’s presence in DRC after the January conflict mirrors its hasty retreat from the Central African Republic following its disastrous mission in 2013.

Read more about Africa

Policymakers in South Africa have faced political pushback over missions such as the DRC stabilization effort. The conversation around these policies has increasingly focused on scrutinizing the specific interests driving such engagements, particularly South Africa’s stake in mineral resources. Since its withdrawal from DRC, Pretoria has struggled to present a clear and consistent position on the ongoing peace process.

In contrast to less accountable regimes, South African military missions are under intense scrutiny from opposition parties, which demand clear justifications for how these actions serve national interests and strengthen regional unity. The Democratic Alliance, South Africa’s main opposition party, criticized the government’s involvement in DRC, describing the SANDF deployment as a “catastrophic failure.” It labeled the SANDF’s claims of a “successful” withdrawal as a “delusional whitewash,” pointing to a chaotic retreat and insufficient air support.

The current political discourse in South Africa suggests a growing disengagement from the crisis in DRC. At the same time, regional organizations are losing their influence as a peace deal, facilitated by the United States and Qatar, becomes the primary focus. This development marks a significant departure from initiatives led by African nations.

U.S.-Qatar security deal sidelines the SADC

The Doha talks, facilitated by Qatar since April, resumed in October following the June Washington peace agreement. The latest round advances security guarantees for DRC in exchange for prioritized U.S. access to key mineral export corridors. This shift underscores Washington’s focus on securing critical mineral supply chains amid its rivalry with China. DRC supplies 70 percent of the world’s cobalt.

While African nations have pursued minerals under the guise of solidarity, the U.S. openly ties security guarantees to mineral access, exposing what regional powers have failed to deliver despite decades of resource extraction. However, the deal’s effectiveness and sustainability will depend on the commitment of key parties, including Rwanda and DRC.

DRC is now being pushed toward a more pragmatic diplomatic approach, focusing on finding partners who are transparent in their intentions rather than those whose mixed interests may impede regional stability. Despite the significant time, resources and effort that African nations have devoted to addressing the crisis in DRC, regional initiatives to resolve the situation have ultimately fallen short. The search for lasting peace has not produced the expected results, leaving a security guarantee for eastern DRC as the only feasible option. Hope is now based on the recently signed peace deal between the M23 rebel group and the DRC government, spearheaded by the U.S. The pressing question remains: What price will Kinshasa pay for such assurance?

×

Scenarios

Likely: The U.S.-Qatar peace framework prevails

The U.S.-brokered peace deal is likely to rein in stubborn players in the DRC conflict, like Rwanda. Kigali could face serious repercussions if it impedes American interests, which is why it is likely to cooperate. However, the security guarantee hinges on access to DRC’s mineral wealth, which could spark long-term internal tension and complicate efforts to achieve lasting peace in the region.

Regional organizations such as the SADC and the EAC will play a diminishing role in negotiations going forward as they are pushed aside by external actors with greater enforcement power.

Unlikely: SADC reclaims leadership

In an unlikely scenario, the SADC will regain its influence in advancing the peace process in DRC. Having invested significantly in the region, the SADC will follow through on its commitment to promoting peace and stability, including engaging Rwanda as a crucial player in the DRC context.

The continent will address the DRC conflict to showcase its ability to tackle one of Africa’s most persistent post-independence challenges. Regional organizations like the SADC and EAC will seek common ground, motivated by the need for regional stability rather than the pursuit of minerals in a war-torn country.

Contact us today for tailored geopolitical insights and industry-specific advisory services.

Sign up for our newsletter

Receive insights from our experts every week in your inbox.