Teens may have come up with a new way to detect, treat Lyme disease using CRISPR gene editing

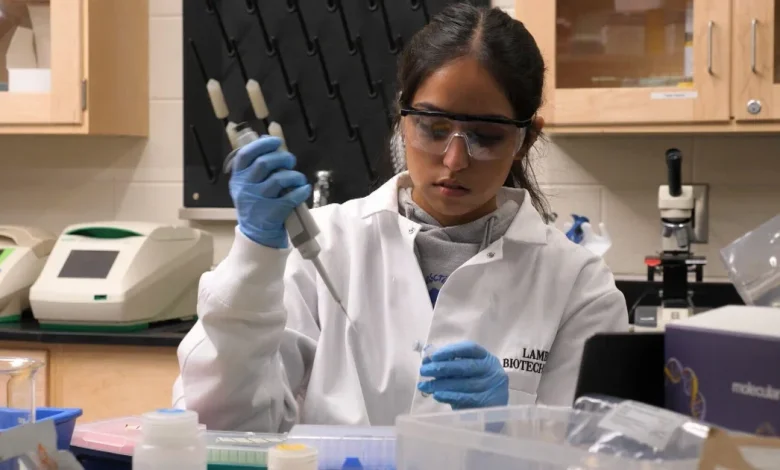

America’s future as a science leader may depend on students like the ones you are going to meet tonight, teenagers from Lambert High School in suburban Atlanta. They may have just found a better way to detect and treat Lyme disease, which affects nearly a half million Americans annually. Their primary tool: the revolutionary gene editing technique known as CRISPR.

And these CRISPR kids did it to try to prove they are the best in the world, competing at a kind of science Olympics in Paris called iGEM – short for International Genetically Engineered Machine. But to win, they would have to go up against teams from China, the rising power in biotechnology.

In Lambert High School’s lab, Sean Lee and his classmates are teenage genetic engineers, manipulating the building blocks of life.

Sean Lee: And what we’re gonna do is you’re going to move each of these samples into these mixes, and these mixes have everything we need in order to amplify our DNA.

Bill Whitaker: It’s currently amplifying?

Sean Lee: Yes. And we’ll have to do this three more times for our different samples.

We went to check out the iGEM team’s project for the big Paris competition. Their presentation seemed more like a pitch from a biotech startup than a public high school science class. Along with Sean, senior Avani Karthik is also a team captain.

Avani Karthik: And so it’s a novel way of CRISPR that detects and so we have to create a guide RNA, and when that guide RNA is recognized the protein gets activated and it collaterally cleaves or cuts everything around it.

Bill Whitaker: That just went right over my head.

60 Minutes

This is light years beyond my biology class, where the high point was dissecting frogs. This is called synthetic biology.

Sean Lee: A popular example of synthetic biology is golden rice where you’re able to engineer this rice to have the specific vitamins that you want so that it’s more nutrient dense.

Rohan Kaushik: And this would sound, like, cliché, but it’s just endless possibilities. So you can just do whatever you want with it, as long as it’s ethically correct.

To compete at iGEM, you need to use synthetic biology to solve real world problems.

These teens set their sights on finding a better way to detect and treat Lyme disease, something that has eluded adult scientists for decades. Transmitted by infected ticks, Lyme can cause arthritis, nerve damage and heart problems if left untreated.

Avani Karthik: One of the biggest problems with Lyme is the lack of, like, being able to diagnose it. So a lotta people will go years. Like, we’ve met someone who went 15 years without a diagnosis.

Current tests make it difficult to detect Lyme in the first two weeks when it’s easiest to treat. Lambert’s big idea for better and earlier detection was to zero in on a protein generated by the infection. Using the gene-editing tool CRISPR and a simulated blood serum, they were able to target specific DNA strands where the protein hides, then snip away extraneous genetic material to expose the protein, enabling them to detect it with a simple, kit-style test – like a COVID or pregnancy strip.

Bill Whitaker: Did you guys ever think, “This is way above my abilities, way above my area of knowledge?” Or you just dive right in?

Sean Lee: Yeah, so– actually we did reach out to a bunch of different professors and stakeholders who gave feedback on our project, and they did tell us in the beginning that this might not be so feasible because you’re trying to tackle such a big thing.

They were also tackling how to treat Lyme. Standard therapy uses antibiotics, but Lambert planned to use CRISPR instead, targeting the bacteria that causes the disease. To make it work, they had to build software to model how best to use CRISPR.

60 Minutes

Bill Whitaker: So as a teacher, is it easy to teach them because they’re so smart?

Kate Sharer: They teach me. Are you kidding? They are so smart that I can’t keep up.

Kate Sharer is their biotechnology teacher.

Kate Sharer: Because they are still teenagers, so they’re thinking so far outta the box. Like, this project in particular, I warned them, this is very high risk, high reward. I can’t imagine any of this working, but I’m happy to help you as much as I can.

Lambert’s team had advantages beyond audacity and brainpower. Their lab is college-level, funded by taxpayers and donors. This is one of Georgia’s most affluent, high-achieving school districts. The student body is majority Asian-American – the iGEM team is entirely Asian-American, children of immigrants.

Lambert also is a sports juggernaut. You can’t miss the signs, but the white iGEM lab coat might be the most coveted uniform of all.

Bill Whitaker: And I understand that parents move to this district so their kids can get into the iGEM program. And not just from Georgia but fr– from around the world.

Kate Sharer: Yes. And there are families that move specifically thinking that, well, my kid’ll be in biotech and then they’ll have a chance to– to try out for the iGEM team.

About 100 students compete for roughly 10 spots on Lambert’s iGEM team each year. Applicants submit a project proposal, take a test and face an interview. Having a special skill like engineering or coding doesn’t hurt. And you have to be willing to put in insanely long hours.

With a month to go, they hit a string of successes.

That stripe showed they could detect Lyme as early as two days after infection – far sooner than the two weeks with existing tests. Senior Claire Lee told us they also saw promising results in treating the disease.

Bill Whitaker: Doctors will be able to use this to identify Lyme disease and, perhaps, treat Lyme disease.

Claire Lee: That’s the goal.

Bill Whitaker: What do you think of that?

Claire Lee: We’re doing something in our high school lab that could potentially have a huge impact for, like, millions of people. It’s not like we’re just saying, like, “Oh. I’m just doing this little thing that–” like, “It might help my grade.” This thing could help save lives.

60 Minutes

What they’ve found is just the first step, much more testing will be needed. But they had more immediate concerns. They raced to finish before the international competition in Paris – pulling all-nighters to write results, code, and build a website explaining their project for the iGEM judges. It takes all that to be best in the world – the award Lambert won in 2022.

Bill Whitaker: Why do you do it?

Avani Karthik: I like to win. And so a lot of this is a competition, so I like to win.

Bill Whitaker: Think you have a really good chance?

Avani Karthik: I think it depends on what the other teams bring.

Hopes were high as the Eiffel Tower when the students from Atlanta landed in Paris at the end of October. More than 400 teams, a third of them high schoolers, were competing in iGEM 2025, elite synthetic biology with a dash of nerd proud culture.

Avani Karthik: My first time coming here, I was so overwhelmed.

This was Avani Karthik’s third year at iGEM and she was keeping an eye on the other teams.

Bill Whitaker: Is there a project here that has blown your mind?

Avani Karthik: Almost every single one.

One was just a few feet away from their booth — Great Bay in Shenzhen, China. Great Bay’s project developed a new enzyme for treating indoor mold. Other high school projects included designing crops to grow on Mars and eye-drops to treat cataracts.

As iGEM teams filled the floor this year at the Paris convention center, one thing was easy to see.

Janet Standeven: In the United States this year, we have 14 high school iGEM teams. Asia has 120.

Janet Standeven runs iGEM’s international high school division. Before this, she taught at Lambert, created its iGEM program and helped it win the grand prize in 2022.

Bill Whitaker: Are you thinking to yourself, “This needs to be in every school?”

Janet Standeven: Yes. Oh. It– that’s been our goal since day one is let’s start with Georgia as a little test bid and see what we can do here.

She left Lambert three years ago after securing federal funding to take synthetic biology to high schools all across Georgia. But the Trump administration cut the money, claiming it fell under DEI – diversity, equity and inclusion. A judge temporarily restored the funding, but Standeven told us she’s not sure it will extend beyond 2026.

Bill Whitaker: What did you think–when your funding got cut?

Janet Standeven: I was devastated. Absolutely devastated. I was angry. And again, I think anybody that’s involved in this work at the high school level realizes this is necessary work.

In Paris, Lambert presented its work on stage. And behind closed doors, the team dressed up to meet a panel of judges, answering questions about their lab work and its real world implications.

Bill Whitaker: Is this what you imagined it would be 20 years ago?

Drew Endy: Hard to imagine this.

Stanford professor Drew Endy was one of iGEM’s founders. Back in the early 2000s, Endy was at MIT teaching genetic engineering and his students had a competitive streak.

60 Minutes

Drew Endy: So we started iGEM because the people who wanted to work with us were the 18-year-olds.

iGEM thrived as biotech boomed. But Endy warned Congress America’s lead in the field is slipping, while China has made synthetic biology a national priority.

Bill Whitaker: How concerned are you that there are not more American participants in– in iGEM?

Drew Endy: I mean, it’s profound concern. It’s urgent that leadership of the next generation of biotechnology has a strong presence in America and it’s represented by young American leaders.

Andy was encouraged by the work done by the team from Georgia and wanted to know more.

Drew Endy: But, like, how do you deliver it?

Claire Lee: Yeah, so we wanna deliver it through lipid nanoparticles.

Endy echoed what other scientists told us, that Lambert’s project could be a major scientific breakthrough, if further testing pans out.

Drew Endy: This year they appear to have developed a better diagnostic for Lyme disease than anything I’ve seen before. It’s not only applicable to Lyme disease, but anything you could find in your blood.

As groundbreaking as their labwork was, Avani Karthik knew Lambert was being judged on everything from their website to their software.

Bill Whitaker: How do you think–you’re going to do?

Avani Karthik: I’m hoping we finish top 10. But even that, I don’t know. We’ll see.

That would be top 10 out of 140 teams.

Bill Whitaker: Fingers crossed. Arms crossed, everything–

Avani Karthik: Yes and knock on wood.

On iGEM’s final day, it was time to see what a year of work had earned Lambert High School. It was a nail biter. They were nominated in five different categories, and kept getting edged out.

They didn’t win the grand prize, that went to China’s Great Bay. But there was joy — they got to storm the stage for best software tool.

Avani Karthik: We thought our project was amazing.

Bill Whitaker: Just a minute–your project was amazing!

Avani Karthik: We’re very proud of it. But it’s what the judges think at the end of the day.

Bill Whitaker: You’re in the top ten in the world.

Avani Karthik: Yes.

Lambert was the only American school to finish in the high school top 10, along with one team from South Korea, one from Taiwan and seven from China.

Produced by Henry Schuster. Associate producer, Sarah Turcotte. Broadcast associate, Mariah Johnson. Edited by Craig Crawford.