Inside the mind of Luigi Mangione

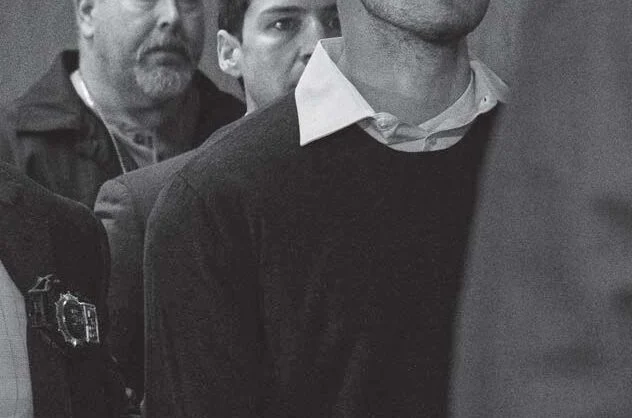

Few vigilantes have had as large a digital footprint as Luigi Mangione, who is accused of killing the UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson last December in Midtown Manhattan. As soon as Mangione was revealed as the prime suspect, his image spread like wildfire across social media. Everyone wanted to understand his motivations. His X-rays, nudes, selfies, deepfakes and Goodreads logs have percolated on forums. But how much do these digital fragments really tell us? While Mangione’s trial has yet to begin, interest in his case has been huge, despite the US government doing everything it could to villainise him before his trial. As many wonder whether the 27-year-old data engineer is a political assassin, hero or mentally ill, a new biography, Luigi: The Making and the Meaning, disrupts the narrative.

Mangione is unusual among true-crime related figures because of the large number of supporters he has. While prosecutors seek the death penalty, many people want him released – whether he’s innocent or not. “Free Luigi” has become a refrain both online and at protests. He is seen as a saint, a hottie, a polite daredevil. He stands for the people, taking on Big Pharma and corporate greed.

After Thompson’s shooting, health insurance companies stripped their websites of employee photos, fearing similar attacks. Meanwhile, many of those following the case who approved of the attack’s apparent vigilante motive hoped Mangione would escape. Instead he was caught eating hash browns at a McDonald’s in Pennsylvania. When he was apprehended, the police discovered a manifesto on him that appeared to claim responsibility for the murder and which condemned the US healthcare system as a punitive abuser of the people in order to acquire “immense profit”. While some commentators praised his anti-capitalist stance, the mainstream press was skittish. The independent journalist Ken Klippenstein was the first to publish the screed in full.

Manifestos are a gift to crime reporters. The journalist John H Richardson, author of this biography, begins by parsing Mangione’s Goodreads review of a different manifesto: by Ted Kaczynski, also known as the Unabomber. It was primarily concerned with “technology’s dark momentum [that] can’t be stopped”. Richardson finds it odd for Mangione to connect with the Unabomber’s work. After all, he worked in tech as a data engineer. He believed in the promise of AI.

Treat yourself or a friend this Christmas to a New Statesman subscription for just £2

Tracking Mangione’s digital footprint has become common route into trying to understand his radicalisation. He followed tech bros and the “Grey Tribe”, a nerdish, arguably classically liberal, online subculture; RFK Jr, now in the Trump administration; and the Democratic Party leftist Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Just as important in the mythos of Mangione is a back injury he suffered from a surfing accident. That changed his politics. He devoured as many ideas as he could. He began travelling in Asia and lost touch with his family for months, eventually ending up in Manhattan where he allegedly shot Thompson three times with a 3D-printed gun. He is reported to have found the weapon blueprint online. It’s a story from a Hollywood film.

Richardson explains how the hidden, back-alley world of the online forum Discord can foster extremism. He examines Mangione’s inspirations for clues, discovering evidence of his internet poisoning: the idea that the online world has infiltrated and influenced our minds in disturbing, chilling and ultimately harmful ways. Mangione reads anti-woke writers like Tim Urban, rationalists like Eliezer Yudkowsky, and Substack writers like Gurwinder Bhogal. It’s a loose network of people trying to push past their personal limits to “save the world”, mostly by improving themselves rather than working together.

“How many young men take on such a sense of personal responsibility for the future of the human race?” Richardson wryly reflects. He turns to Mangione’s past hobbies in search of answers, a steady diet of magic mushrooms and video games. He had at least some interest in girls, though Richardson ignores Mangione’s rumoured bisexuality, a growing part of his online mystique, instead chronicling a burgeoning friendship on X with a troubled right-wing troll. While Mangione has been involved in a flurry of online scraps, the truth is buried in conflicting contexts. If Mangione was connected to more insidious online groups than it would seem from the occasional messages he traded with like-minded thinkers, he left no trace.

Some fringe radical groups online, such as the Zizians, began as small communities on platforms like Discord where members shared grievances and philosophical musings. They are now alleged to be involved in the violent deaths of six people across the US. Richardson makes a curious link between the Zizians and Mangione, suggesting the internet’s unique mix of isolation and narcissism fuels idealistic violence. The difference is that while many groups are easily derided as mentally ill or maniacally cruel, Mangione seems to remain cool, collected and focused.

This is the kind of story Richardson would seem primed to tell. He was previously a staff writer at Esquire and New York magazine, covering high-profile crime stories with narrative flair. His 2005 article on musical theatre at New York’s Sing Sing prison was the inspiration for the eponymous 2023 film. Richardson’s “biography” of Mangione, however, is everything but. Rather than telling the story of its subject, it is book is about eco-terrorism. It traces Mangione’s ideas not to radicals like Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti – 1920s anarchists also accused of murder – as others have done, but to the Unabomber’s acts of eco-terrorism while living off the grid in rural Montana.

It’s frustrating that Luigi: The Making and the Meaning is so disorganised, a Matryoshka doll that keeps opening only to reveal the Unabomber, not Mangione, at the centre. Richardson’s letters with Kaczynski form the book’s narrative spine. Richardson, ever the dogged reporter, sends letters off to Mangione, but never hears back.

Condescension towards Mangione runs throughout the book. Richardson is certainly not interested in letting his subject off the hook. But a good biographer should, perhaps, be a little enamoured with their subject. Otherwise their account risks reading like a cold shower. Richardson is quick to point out that the Unabomber influenced not only eco-terrorists on the left, but also neo-Nazis, accelerationists and eco-fascists. Rarely does Richardson consider his role as biographer and commentator in the sanctification of Mangione, only partially admitting he enjoyed the spectacle of “shock-scrolling” on X when the crime began to unfold. He wonders if the sheer amount of posting by others was a celebration of nihilism or politically inspired optimism. But Mangione belongs to neither the left nor the right. He is a populist, and was received by the public as one. He was praised by people from across the political spectrum but disavowed by the mainstream media and parties. At protests, some attendees made signs with the three words “delay”, “deny”, “depose”, which were found inscribed on shell casings at the crime scene.

While Richardson threads Mangione’s story throughout the book, he is primarily concerned with the world’s descent into radical chaos. Some amount of alarmism is warranted. But how to respond? A growing number of political pundits have exploited the turbulence for their own ends. Richardson points to certain fascists and Nazis as proof of left and right blending together online. Violence has expanded on both sides, but to claim that monarchists like Curtis Yarvin demonstrate the melding of the two poles of the political spectrum, as Richardson does, is crude and false.

There could be something of value to this genealogy of extremism, but Richardson loses perspective, zooming in on the extraordinary and overlooking more mundane details. His book feels like a college thesis retrofitted to a relevant news peg. The closest Richardson comes to an epiphany is when he begins to link the role of the extremist with a saviour narrative, delving into the online world of “main-character syndrome” and “non-player character” (NPCs). Such slippery ideas, based on video-game terminology, refer to the wilderness of online forums, where posters are encouraged to see themselves as captains not only of their own fate but the world’s.

Those who don’t engage in action are the people Mangione calls NPCs, people who wander around in a daze, doing nothing. Richardson seems more attracted to those who take on the mantle of global responsibility. This saviour complex consumes many budding radicals Richardson interviews in the course of his research. “I want to come out in a few years and be like Jesus,” one says, “healing people with plant medicine.” Of course, it’s not all non-violent magic. He also wants to tear down the existing order of things. But even aloof gods of the anti-tech movement, such as Kaczynski, think the way forward requires “people… learning how to mobilise and organise resistance”. This may be the real divide that these players struggle with – beyond motives or tactics – the inherent tension between the individual and the public. Do we do it alone or build something better together?

Luigi: The Making and the Meaning

John H Richardson

Simon & Schuster, 272pp, £20

Purchasing a book may earn the NS a commission from Bookshop.org, who support independent bookshops

[Further reading: Iris Murdoch’s poems were better left in the attic]

Content from our partners

This article appears in the 26 Nov 2025 issue of the New Statesman, The Last Stand