‘Heated Rivalry’ is the steamy hockey romance we deserve

In the canon of gay film and TV, there are near-universal touchstones.

The ostracization or bullying of young boys who don’t fit within norms. The emergence of one’s authentic or artistic voice on the rocky road of adolescence. Tearful confessions of love—to peers, parents, teachers or mentors—admitting finally, “This is who I am.”

Such is the arc of gay hits like Red, White & Royal Blue and Love, Simon in the film world, or shows like Heartstopper, Young Royals and Love, Victor.

It’s not a far leap, then, to assume that Heated Rivalry—Crave’s love story between two young athletes entering the world of professional hockey—would follow those traditions. Like all of the aforementioned titles, Heated Rivalry is based on a book written by a woman (Rachel Reid) and adored among female #BookTok fans.

Yet the show, kicking off with a two-episode premiere on Nov. 28, is a far cry from its more sentimental, saccharine siblings. Refreshingly so.

Get free Xtra newsletters

Xtra is being blocked on Facebook and Instagram for Canadians as part of Meta’s response to Bill C18. Stay connected, and tell a friend.

After all, as much as surviving bullies and unrequited crushes are quintessential gay experiences, so too is stroking yourself next to a stranger in the shower, or putting on your clothes to leave some guy’s place mere seconds after swallowing his load. Are these common experiences any less authentically gay? Any less deserving of screen time?

If your answer is no, Heated Rivalry is the show for you. Both above examples—and much, much more—take place in the first of six episodes in the series, shared with Xtra ahead of its premiere.

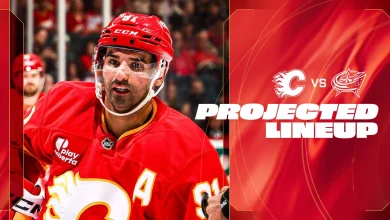

The pilot introduces us to Shane Hollander (Hudson Williams), a teenage Japanese-Canadian savant with the stick trying to live up to expectations of hockey-obsessed Canadian fans and demanding parents. Then there’s Ilya Rozanov (Connor Storrie), a boastful Russian import with the skills on the ice to back up his swagger. Though the premiere episode moves at breakneck pace—there are several time-jumps as the boys cross paths at different games, cities, events—it sets up a compelling enemies-to-lovers dynamic.

Heated Rivalry has every ingredient for success: an existing, passionate fan base; sex scenes as raw and revealing as those in White Lotus or Game of Thrones; and stars who fully embody their roles—from Williams’s turning confident to bashful on a dime, to Storrie’s comedic cadence and teasing smirk.

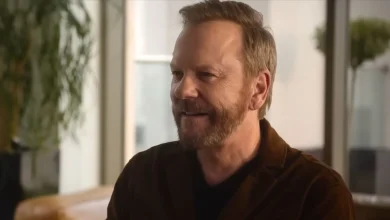

The real MVP, however, is writer-director-producer Jacob Tierney. With Heated Rivalry, Tierney has turned pulp into premium TV—an achievement he and perhaps he alone is suited for. The Canadian creator behind projects like Letterkenny and Shoresy clearly has a knack for laugh- and love-infused hockey TV, and in discussing Heated Rivalry, it’s clear how much heart Tierney has poured into the series. As proof, one can look to the fact that he DM’d author Reid to get the rights, or the remarkably fast development pipeline (a mere two years after that initial outreach, almost unheard of in scripted TV).

To learn more about why Tierney took such a liking to the story, and to hear from its breakout stars, Xtra sat down with Tierney, Williams and Storrie to talk all things Heated Rivalry.

Let’s start with expectations. Naturally, hearing that Heated Rivalry is based on a book authored by a woman and very popular with women, I assumed it was in a certain vein of other gay romances. Jacob, what misconceptions or assumptions were you facing when you were pitching and developing Heated Rivalry?

Jacob Tierney: I think there is a lot of misunderstanding about romance as a genre, and about women’s tastes, because of inherent misogyny and people’s lack of interest in things that interest women. And, you know, romance is an industry that makes a billion dollars a year and yet is wildly unrepresented outside of literature. I think we’re seeing more of it coming into the fray, but the misunderstanding is a total lack of curiosity about things that pleasure women in general.

When you slid into Rachel [Reid]’s DMs to collaborate on an adaptation of her book, how did you sell your vision? Were there initial promises you made?

JT: I didn’t even know Rachel was Canadian, so I didn’t have any idea if she even had any sense of who I was. But she was a fan of Letterkenny, she was a fan of Shoresy. What I told her that I think probably sealed the deal was I wanna take these books seriously. Like, I don’t want to do this as a Hallmark romance. I want to take this seriously and I want to give it six hours, which is a different treatment than I think this genre generally gets.

Hudson and Connor, typically in interviews for romances you’re asked about chemistry. I’m curious about, in this enemies-to-lovers story, how you kept that disdain and animosity alive in the earlier parts of the story, especially as you were becoming friends off-camera.

Hudson Williams (laughs): I secretly hate Connor in real life. So it was very easy.

Connor Storrie: And I love Hudson. So that hurts my feelings.

HW: Easy-peasy. I would say, at least for me. It’s there in the script that Ilya’s not a great communicator to Shane. As an audience member, I can fully justify his actions, I can empathize. But on those days when I’m standing across from him and he says nothing, he communicates so little about what’s going on internally, I have no reason to accept or empathize with his situation. He’s not really extending the olive branch. I found it pretty easy to just get pissed off trying to communicate with him and open up my feelings with Ilya, the character.

CS: Yeah, I feel the same. Our characters are pretty different from us, so once we do lock into that, I think that natural friction comes up. But yeah, it’s a really interesting balance because you instantly go from that friction or that envy into romance. It’s kinetic energy. You can turn that into a loving thing, and then you can also turn that into a passionate thing or you can turn that into a disdained thing.

JT: Yeah, it’s just a lot of energy being directed at the other person. And it’s easy to kind of shift that over from humour to animosity to sex to whatever it wants to be.

I’m glad you mentioned humour because it’s interesting how many comedic moments there are in the pilot, especially with Ilya. Hudson, is there like an element of playfulness in Shane that people don’t understand, or will he continue to be the “straight man”—for lack of a better word—to Ilya’s jokes?

HW: I had one of (author) Rachel Reid’s friends tell me she found Shane very funny, thank you very much. But yeah, I do agree with you. He’s sort of a square, which allows Ilya to be the more charismatic, fun one. The juxtaposition is sort of what drives the story.

JT: Shane gets his laughs later. Yeah, you’ve got a bunch of funny moments.

CS: Also I would say that there’s a difference between laughing at someone and laughing with someone. I feel like the Ilya moments are me reacting to him. And so the audience is in on it, right? Because it’s my reaction or to something that is funny. But then there are moments, like before the first time Ilya comes over [to Shane’s room], and you’re in a suit, dressed dead-ass serious. And then that’s hilarious because you’re not in on it, you know.

JT: It’s just a different type of funny. He’s just not a showman. He’s not a joke man. He’s a real kind of classic hockey player in that way. And Ilya kind of has a bit more of a “I don’t give a fuck” attitude.

Hudson Williams and Connor Storrie play Shane Hollander and Ilya Rozanov, up-and-coming hockey rivals competing for the game’s top spot. Credit: Courtesy of Crave

Connor, there’s an image of you from a past project (Riley, 2023) that’s been shared side by side with your Heated Rivalry pics as an example of “Twink Death.” I’m wondering for both of you, as your bodies change and you come into these like very muscular roles, is it affecting how you act? Is it affecting your careers?

CS: I think so, yeah. I go through a ton of phases. That was my alt-vegan phase—I was vegan for three years. And then directly after that, I went into my bodybuilder phase that ultimately led to Heated Rivalry. I’m always changing. I had a million other phases before this one too. I think that’s kind of what acting is, and I think that bleeds into my real life a little bit. It’s just playing with your presence and what you look like.

JT: We also talked about it. I was like, “Hockey players eat pasta every day. They should not look cut or veiny. They’re big, they’re beefy, but we don’t want them to look like they go to a gym for aesthetics.” These are athletes that use their bodies, and also it’s a long show. I wanted everybody eating, feeding their energy, their brains, all that stuff. So yeah, we tried to do everything in a healthy way that felt as right as it could for hockey as well, which is not swimming and it’s not running. Like, it’s a very different sport in that sense.

“Sex is a language in this show to tell a story”

Speaking of bodies, you worked closely with intimacy coordinator Chala Hunter. There’s sometimes a misconception that intimacy coordinators are solely there to prevent people from stepping over the line or making others feel uncomfortable. I think they can actually heighten and add to the sexiness. How does the presence of an intimacy coordinator impact your sex scenes?

HW: I’ve had stifling intimacy coordinators before, where sometimes it’s too rehearsed or too restricted to the point where the actors are saying, “We can go further than this.” Our show, even though we had to get good blocking and choreography and the technical stuff down, after that we talked about the who, what, where and when. Asking ourselves, “What does this mean in the story?” And then that almost needs to be reminded because you can be up in your head about the technical aspects. And I think Chala was a good reminder of, “Okay, you still need to sell this.”

JT: These sex scenes were also very scripted and very specific on the page. I know as an actor that the last thing I want to be told is, “Go at it.” It’s not fun for either party. Also, sex is a language in this show to tell a story, so everything was very specific. Everything was choreographed much like a dance, so Chala was our choreographer in a way. Once you learn the steps, then you’re free to express yourself so you don’t have to be thinking: “What am I supposed to do next? Where does my hand go?”

Because again, there’s so much sex, and it has to change. They start off very young and they end up being people who’ve been having sex for years, who know each other’s bodies. But at first it’s all exploration and it’s all tentative. It’s all discovery, but it’s also fear. There’s so much going on.

In the vein of your earlier answer, Connor, about the personal bleeding into the professional, there’s been an ongoing conversation about queer people playing queer roles. I’m conflicted about this because on the one hand, it’s no one’s business. On the other hand, this book and this story is, in part, about living authentically and openly. Do you feel there’s a need to talk about your personal lives in relation to this project?

JT: I’ll answer this for them. I don’t think there’s any reason to get into that stuff. I’ll tell you something about the casting of both of these roles. You can’t ask questions like that when you’re casting, right? It’s actually against the law. So what you have to gauge is somebody’s enthusiasm and willingness to do the work. And that’s what’s so impressive about both of these guys is they came into this being like, “Yeah, we’re here to do this, and we are here to make this story feel authentic and to be as real as possible.” And they fucking hit it out of the park.

In that casting process, does anything like come up for you when you reflect on those initial meetings and reading together?

HW: I remember Connor being very hard to get through, which only fed my performance because he was hard to reach and it was frustrating. He was going off script, taking very long pauses and some liberties. He walked out of his Zoom frame and I had to call him back into frame. And it was great. I remember I got a rise out of him: it was like half a smile and like a tinge of an eyebrow.

CS: Yeah, something that sticks out to me, and something that people don’t really talk about a lot is that different projects have different tones built into them. Like, if this is on a certain network or a certain channel, or a certain type of TV show, that’s gonna have a certain vibe and a certain tone. It felt very obvious to me the moment that I read with Hudson that we were making the same TV show.

JT: They read together and we were all like, “Oh my god, this is fucking done. Flush the rest of it down the toilet.” Their chemistry was just insane. It was always going to be about chemistry. We loved both of them separately and then seeing them together, it was just like perfection. We couldn’t ask for more.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.