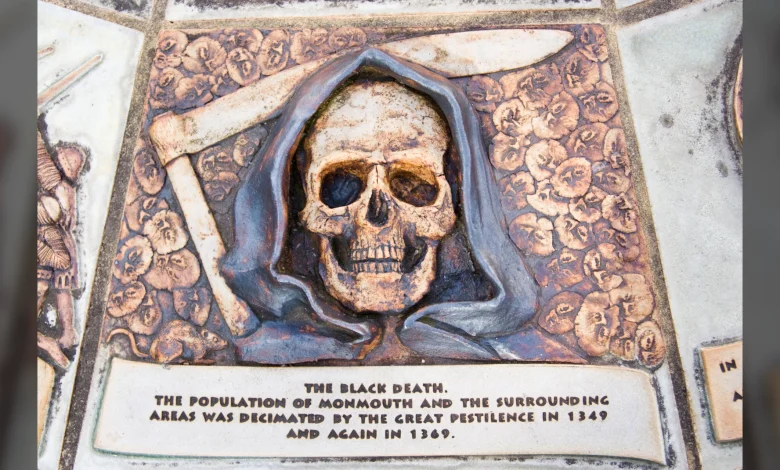

Volcanic eruption triggered ‘butterfly effect’ that led to the Black Death, researchers find

An unknown volcanic eruption in the mid-14th century may have set the stage for the spread of the Black Death in Europe, according to a new study. By triggering a cool and overcast period in the Mediterranean, the eruption started a domino effect that led to a downturn in agricultural production, which required merchants to import grain — and the bacterium Yersinia pestis that causes bubonic plague — via the Black Sea.

The bubonic plague pandemic, more commonly known as the Black Death, reached Europe in 1347 and quickly affected Italian port cities. The plague then spread throughout Europe over the next few years, resulting in the deaths of between 30% and 60% of the population.

You may like

To answer this question, Bauch and Ulf Büntgen, a geographer at the University of Cambridge, investigated climate-driven changes in the Mediterranean that could explain the sudden appearance of the Black Death in 1347. Their research was published Thursday (Dec. 4) in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

When combing through contemporaneous historical accounts, the researchers noticed reports of reduced sunshine, increased cloudiness and a dark lunar eclipse, all independently reported by observers in parts of Asia and Europe between 1345 and 1349. All of these astronomical and weather phenomena could be attributed to a large-scale volcanic aerosol layer, which has been known to cause cold spells as the sulfate aerosols reflect sunlight back into space.

Paleoclimate data gave the researchers a clue: High amounts of sulfur in polar ice cores suggested one or more eruptions of a previously unknown volcano around 1345.

“We cannot say very much about the volcanic eruption,” Bauch said. “From the ice cores, we know that the eruption must have taken place in the tropics, because sulfate was found in similar concentrations in the ice of both the North and South Poles.”

The researchers also looked at tree-ring data from around Europe and discovered that the summers of 1345, 1346 and 1347 were much colder than normal while the autumns were much wetter, causing soil erosion and flooding. Historical records also confirmed that changes in the environment had decreased the yield of a number of crops, including the grape harvest and grain production in Italy, requiring merchants to begin importing products from the Black Sea area to prevent famine.

“Upon return in the second half of 1347 CE, the Italian trade fleets, however, not only brought grain back to the Mediterranean harbours, but also carried the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis most likely via fleas that were feeding on grain dust during their long journey,” the researchers wrote in the study.

The first cases of plague in humans were reported in Venice just a few weeks after the arrival of the last grain ships. “This initiates the typical infection cycle,” Bauch said. “Rodent populations are infected first; once they die off, the fleas shift to other mammals and ultimately to humans.”

You may like

Importing grain after several years’ worth of volcano-induced climate change therefore prevented a Mediterranean-wide famine but also introduced the Black Death into Europe, the study authors proposed.

“This study brings in new information on the 1345 volcano, which helps explain why the Black Death — that is, the epidemic well-documented in sources from 1346 to 1350 — happened when it did,” Monica H. Green, an independent scholar and expert on the Black Death who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. “But it happened how it did — with a ‘plague infrastructure’ of rodents and insect vectors already established — because local reservoirs had already been established.”

The onset of the Black Death resulted from a unique-but-random combination of short-term factors, like climate, and long-term factors, like the grain distribution system in Italy, the researchers wrote in the study.

Even though the Black Death resulted from a rare confluence of environmental and social factors, it’s important to gain a better understanding of the causes of past pandemics, the researchers wrote, because “the probability of zoonotic infectious diseases to emerge and translate into pandemics is likely to increase in both a globalised and warmer world.”