Climate-driven changes in Mediterranean grain trade mitigated famine but introduced the Black Death to medieval Europe | Communications Earth & Environment

While much attention has been paid to the putative volcano-climate-human nexus at the beginning of the Late Antique Little Ice Age (LALIA) and the onset of Justinianic plague between 536 and 541 CE32, little effort has been made to evaluate the climate response and societal consequence of a yet unidentified but likely tropical volcanic eruption – or cluster of eruptions – around 1345 CE33,34 (Fig. 1A). Exceeding the sulphur yield of the well-studied Mount Pinatubo eruption in 1991 substantially35, the volcanic stratospheric sulphur injection in 1345 CE amounts to an estimated 14 Teragram (Tg)33. The climate-relevant signal in 1345 CE ranks 18 over the past 2000 years and was preceded by at least three volcanic eruptions in circa 1329, 1336 and 1341 CE. The reconstructed sulphur injections of these events are circa 3.7, 0.7 and 1.2 Tg, and the first and last eruption likely occurred in the Northern Hemisphere extra-tropics.

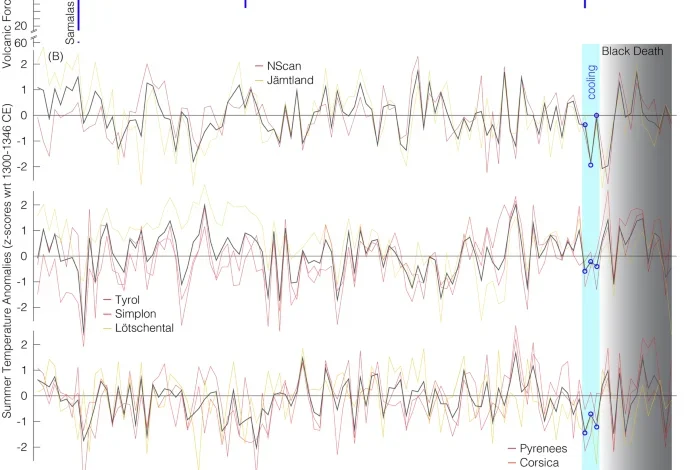

Fig. 1: Volcanic forcing and summer cooling.

A Estimates of volcanic stratospheric sulphur injection (VSSI) derived from the geo-chemical analysis of ice cores collected in Antarctica and Greenland (eVolv2k 3 v)33. The VSSI is expressed in Teragram (1 Tg = 1012 g). For comparison, please consider that the climate-relevant VSSI of the 1991 Pinatubo eruption was 6 Tg. The only known eruption between 1250 and 1360 CE is Samalas dated to 1257 CE, whereas all other nine VSSI signals originate from yet unidentified source volcanoes, for which locations have been estimated to the Northern or Southern Hemisphere extra-tropics (NH or SH), or the tropics. B Comparison of annually resolved and absolutely dated summer temperature reconstructions that use maximum latewood density (MXD) measurements from hundreds and thousands of core and disc samples from living and relict trees collected in eight different regions across Europe (see Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Data S9 for details). The individual records are expressed as z-scores with respect to the 1300–1346 CE pre-Black Death period (mean of zero and standard deviation of one), and the thicker black lines are the regional means. The three blue circles and the light blue shading refer to 1345, 1346 and 1347 CE.

Observers in Japan and China, as well as Germany, France and Italy independently reported reduced sunshine and increased cloudiness between 1345 and 1349 CE (Supplementary Data S1). The atmospheric perturbation of a possible sulphur-rich volcanic eruption in circa 1345 CE is further corroborated by signs of a dark lunar eclipse. Associated with a volcanic dust veil, such a rare phenomenon is the obscurity of a normally reddish-brownish full lunar eclipse and can be considered a reliable sign of otherwise underreported aerosol layers following large volcanic eruptions36. Although we recognize the uncertainty of historical accounts, recalculations did not confirm the reported lunar eclipses from Bohemia and China (Supplementary Data S1). We therefore argue that reduced atmospheric visibility, in combination with reports about foggy skies from Europe and Asia make a large-scale volcanic aerosol layer around 1345 CE very likely.

Furthermore, a lack of cell wall lignification expressed by the occurrence of two consecutive Blue Rings in a high-elevation tree-ring chronology from the central Spanish Pyrenees could be indicative of at least two ephemeral cold spells that affected ring formation during the growing seasons of 1345 and 1346 CE37 (Supplementary Fig. 1). While so-called Blue Rings are usually considered discrete wood anatomical features, their consecutive occurrence is extremely rare. Despite remaining uncertainties in the understanding of the mechanistic drivers of Blue Ring formation, the succeeding examples from the Pyrenees almost certainly refer to exceptional summer temperature drops in the Pyrenees, and possibly also over Iberia and even across much of the western Mediterranean region. Although the spatial extent of severe temperature anomalies is typically widespread, their intensity and duration remain unknown.

Distinct summer cooling in 1345–1347 CE is also eminent in a large-scale temperature reconstruction that uses maximum latewood density (MXD) instead of tree-ring width (TRW) measurements to accurately capture year-to-year and longer changes in growing season temperatures38 (Supplementary Fig. S2). The consecutive summer cooling between 1345 and 1347 CE was the coldest period in the Northern Hemisphere extra-tropics since the marked post-eruption cold spell of the tropical Samalas volcano dated to 1257 CE. Possible linkages between large-scale summer cooling and the establishment of the second plague pandemic, however, have so far only been addressed marginally29,39,40.

Re-assessments of eight MXD-based warm season temperature reconstructions from northern Scandinavia (two records), the Swiss and Austrian Alps (three records), and the central Spanish Pyrenees, Corsica and northern Greece (each one record) reveal three cold summers in 1345, 1346 and 1347 CE (Fig. 1B; Supplementary Table S1). The temperature depression is most distinct across the Mediterranean region, where 1345 CE marks the coldest summer (in line with the anatomical Blue Ring evidence). Although the situation is less clear for hydroclimate (Supplementary Fig. S3; Supplementary Table S2), central European summers were likely dryer than average between 1345 and 1347 CE, and a prolonged west-east dipole structure south of the Alpine arc suggests wetter conditions over Greece but moderate aridity over Morocco. Caution is advised since the hydroclimate reconstructions tend to reflect regional rather than synoptic scale signals and contain less signal strength compared to the temperature records41. Looking at a set of year-to-year maps of TRW-based spatially explicit reconstructions of summer wetness and dryness over Europe and the Mediterranean basin reveals relatively dry growing season conditions in 1346 and 1347 CE across large parts of the British Isles, northern France, the Low Countries, Germany and southern Scandinavia42 (Supplementary Fig. S4). In contrast, much of the Iberian Peninsula, Italy and the Balkans received above average spring and summer precipitation in the years before the Black Death. However, this pattern is not in full agreement with historical weather reports from Italy43 (Supplementary Data S2).

To complement our paleoclimatic insights obtained from the dendrochronological dataset, we evaluated the available narrative and administrative sources that contained information on weather conditions at sub-seasonal resolution (Supplementary Data S1-S7). Documentary evidence suggests that climatic changes and environmental factors in different parts of Europe and the Mediterranean impacted agricultural productivity from autumn 1345 CE onwards (Supplementary Data S3). As a consequence, grape harvest failures and extremely low grape yields were reported for northwestern Italy (Supplementary Data S8). The autumn of 1345 CE, as well as the springs of 1346 and 1347 CE were characterised by heavy precipitation that caused severe flooding and soil erosion in Italy, including the Po valley and the Italian regions of Tuscany and Lazio. While the winter of 1344/45 CE was particularly cold and snowy in the Middle East, drought spells and locust invasions impacted agriculture across the Levant in the winters of 1345/46 and 1347/48 CE (Supplementary Data S2).

Convincingly, most of the contemporary observers from France and Italy, including prestigious academics from Paris, independently reported a series of exceptionally cold and wet summers and overall unusual weather anomalies before the Black Death reached Europe in 1347 CE (Supplementary Data S1). Even so cooler than average summer conditions in 1348 CE would explain unusually high plague-related mortality peaks for Italy6, no such evidence is obtained from the tree ring-based reconstructions for central Europe and the Mediterranean (Fig. 1B). Moreover, detailed weather descriptions are rare after 1347 CE, because emerging plague outbreaks increasingly captured contemporary attention.

Late Medieval Italy was highly urbanized44, and the rise of self-governing city-states between the mid-12th century and around 1350 CE entailed a complex grain supply system to ensure food security. The city-states established institutions and started to import grain over long distances, because of their fast-rising populations and the limited scope for expanding the productivity of their agricultural systems. Only Milan and Rome were largely self-sufficient, whereas Bologna, Florence, Genoa, Siena, and Venice, as well as many smaller cities relied on grain imports45,46. It is therefore no surprise that the first communal granaries in Italy were developed in response to poor harvests and the need to store supplies for military conflicts. Newly emerging grain authorities employed officials to enforce regulations, manage granaries, purchase and transport cereals, and organize sales. The primary regulatory measure was a ban on grain exports from the city’s territory. Compulsory levies, import premiums, and various sales and storage regulations were additionally imposed, with violations punished by severe fines and property confiscation. Communal grain imports were organized through merchants, financed by voluntary of forced loans and indirect levies on grain trade, mills, and bread production45,46,47. Grain measures were the second most expensive policy of many Italian city-states after military spendings. Since the 1250s CE, large maritime republics like Venice, Genoa and Pisa established treaties with grain-exporting regions such as Apulia, Sicily, Sardinia, and various political powers in northern Africa. Roughly a decade later, Venice and Genoa started to establish sophisticated trade posts and proto-colonial networks in place to access grain from the Aegean and Black Sea regions to prevent mass starvation in the case of climate-induced, supra-regional famines across much of the western and central Mediterranean basin23,47.

Severe dearth and famine in 1346/47 CE affected large parts of Spain, southern France, northern and central Italy, Egypt, and the Levant simultaneously. Chronicles reveal independent evidence for substantial price peaks in cereals across modern-day Catalonia, northern and central Italy, Egypt, and even the Hejaz on the Arabic Peninsula (Fig. 2A). The highest wheat prices for at least eight decades were recorded in all regions in 1347 CE (Supplementary Data S6-7). This trans-Mediterranean dearth probably led to high mortality rates in many cities of northern Italy that suffered from malnutrition and epidemics, but not yet from plague caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis29. Grain trade regulations started in 1346 CE and were partially accompanied or forced by civil unrest. Associated policy measures in north-central Italy reached their highest level in 1347 CE for at least one century (Fig. 2B). Although not necessarily, but possibly related to widespread famine and the onset of the Black Death, the lowest building activity in central Europe since medieval times was reconstructed for 1348–1350 CE48.

Fig. 2: Wheat price and policy measures.

A Mediterranean wheat price based on individual grain, wheat and millet price reconstructions from Catalonia, Tuscany (Firenze, San Miniato, Siena), the Po Valley (Bologna and Parma), Cairo and Mekka (Supplementary Data S6-7). The record is expressed as z-scores with respect to 1300–1346 CE (mean of zero and standard deviation of one). B Grain policy measures in north-central Italy47.

Spatial synchrony of the reported famines in 1346/47 CE suggests a larger climatic rather than a regional socio-economic driver. This argument is corroborated by temperature-sensitive grape harvest data from north-western Italy49, which exhibit a sequence of extremely low yields between 1345 and 1350 CE (Supplementary Data S8). While grain was initially imported from southern Italy (Supplementary Data S4), the large-scale harvest failure required additional oversea imports (Fig. 3), and Genoa and Venice were encouraged to agree on a ceasefire in an ongoing conflict with the Mongols of the Golden Horde50. In 1349 CE, Venetian sources stated explicitly in retrospective that it was Black Sea grain that saved the city from starvation. This statement is further supported by reports of food scarcity in Venice and the need to import grain from the Black Sea at any price in April and August 1347 CE (Supplementary Data S4). While the long-distance maritime transmission of the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis via grain ships might have occurred sooner or later, it is the cold and wet climate downturn in 1345 and 1346 CE, possibly caused by volcanic eruption(s), together with subsequent food shortages that can provide a mechanistic explanation for the synchronised onset of the second plague pandemic in many major Italian sea ports in 1347 CE and its spread (or absence of outbreaks) in 1348 CE across Italy and nearby regions of the Mediterranean basin (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3: Grain trade and plague dispersal.

Main aspects of the Venetian, Genoese and Pisan grain trade network that prevented much of Italy from starvation in 1347 CE but also brought the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis to Venice and other Mediterranean harbours during the second half of 1347 CE (Table 1), from where it spread rapidly. Location of the tree ring-based climate reconstructions is indicated (with two sites in Scandinavia not shown). Map is an equal-area, pseudo-cylindrical Mollweide projection with greyscale referring to elevations above sea level.

Fig. 4: Onset of the Black Death in southern Europe.

A The first reported plague outbreaks in 1347 CE in southern Europe (red stars), together with the assumed routes of Venetian and Genoese grain ships (black lines). B Subsequently reported plague outbreaks between January and May 1348 CE (orange stars), together with earlier outbreaks (red stars). C Plague outbreaks reported in June 1348 CE or with unspecified date in the same year (yellow stars), superimposed on earlier outbreaks (orange and red stars). D All known plague outbreaks in 1347 and 1348 CE (red, orange and yellow stars), together with major Italian cities and regions that were most likely not affected by the Black Death during this period (green stars). Supplementary Data S4-5 (and ref. 4.) provide details on plague outbreaks, stars refer to cities while less specific locations are indicated by shadings of the same colour codes, and the map is an equal-area, pseudo-cylindrical Mollweide projection with greyscale referring to elevations above sea level.

Lifting the grain embargo on the Golden Horde in April 1347 CE enabled Italian trade ships to reach the northern Black Sea coast and the Sea of Azov. Maritime contact with this region provided access to the trade hubs there and important grain producing areas to the north that were arguably not affected by unfavourable climate at that time51, as they would, otherwise, not been able to supply huge amounts of grain to Italy. Upon return in the second half of 1347 CE, the Italian trade fleets, however, not only brought grain back to the Mediterranean harbours, but also carried the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis most likely via fleas that were feeding on grain dust during their long journey (Figs. 3, 4A; Table 1) (Supplementary Data S5). The first human plague cases in Venice were reported less than two months after the arrival of the last grain ships23,52 (Fig. 4B). This mechanism also provides insights into the further spread of the Black Death in mainland Italy (Fig. 4A-C). The re-start of Venetian grain exports to Padua in March 1348 CE further explains in perfect chronological order the subsequent plague outbreak there (Fig. 4C; Supplementary Data S4-5). Such a temporal synchronization is more difficult to demonstrate for Florence and Siena, although the ongoing need to replenish cereal supplies while the famine was already abating is clearly visible (Supplementary Data S4-5). Since major Italian cities like Rome and Milan, large cities of the Po plain under Milanese rule but also cities in grain-producing areas like Verona, Ferrara, Ravenna and Bari did not participate in grain imports from the Black Sea region in 1347/48 CE, they were exempted from the first wave of plague outbreaks (Fig. 4D; Supplementary Data S4-5). By contrast, other important Mediterranean harbour towns, including Marseille and Palma de Mallorca, witnessed outbreaks already at the end of December 1347 CE4,53, probably brought by Genoese ships allegedly carrying grain as previously agreed. A similar pattern is evident in the secondary outbreaks of April 1348 CE in smaller ports such as Savona, Ventimiglia and Tunis4, which might have received grain shipments after the Genoese had fully restocked their own supplies. A grain surplus in Venice, together with subsequent exports to refill empty granaries as it had happened in Padua, probably distributed plague to Trento and from there to different regions of the European Alps in the second half of 1348 CE4.

Table 1 Socio-economic activities relevant to the first plague outbreaks at the onset of the Black Death

Easing of a decadal-long papal trade embargo since 1344 CE also allowed Italian merchants to resume their relationships with the Mamluks in the Middle East54,55, and a huge cargo ship was built in Venice to export cereals to Alexandria. Latin trade agreements with Egypt and Syria also flourished between 1345 and 1347 CE, Mamluk merchants were present in Crimean harbour towns, and grain from Anatolia and some eastern Mediterranean islands was most likely shipped to Egypt (Fig. 3; Table 1) (Supplementary Data S4). While individual grain shipments cannot be traced back, there is strong economic and political indication that grain ships from the Black Sea not only brought the Black Death to Italy (i.e., transported the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis), but also to the Middle East and northern Africa (Figs. 3, 4C; Table 1). This becomes even more likely since we know that the Mamluk sultanate imported grain during other food supply crises of the late-13th and 14th centuries CE56.

Our study demonstrates that climate-induced long-distance grain imports during and after a supra-regional famine not only prevented large parts of southern Europe and the Middle East from starvation but at the same time introduced plague to many Mediterranean harbours and further facilitated its rapid dispersal across the Old World. The high level of spread and virulence of the Black Death are both possibly connected to well-established and long-lasting structures of grain provisioning and the devastating effects of previous famines that weakened Europe’s populations just before the arrival of the plague bacterium. In other words, the sophisticated Italian food security system that provided resilience to many famines over at least one century, ironically became a gateway for a mortal danger to pre-modern Europe. We consequently consider the Black Death not just as a striking interaction of climate, famine and disease, rightfully acknowledged as the climax of the 14th century crisis57, but as an early ramification of globalisation. Modern risk assessments may therefore incorporate knowledge from well-document climate-disease interactions that affected past societies.

Our findings suggest that the onset of the Black Death, the largest known plague pandemic in human history that killed a large part of Europe’s population in just a few years after 1347 CE, most likely resulted from a unique, though random interplay of direct and indirect, natural and societal parameters operating on various spatiotemporal scales; ranging from local short-term events like volcanic eruptions and military actions to short-term, yet large-scale harvest failure and long-term developments like the pan-Mediterranean grain supply system. We explain the timing and spread of the Black Death by the activation of well-established emergency measures, causing unintended and unpredictable consequences within a complex socio-ecological system. Long-distance maritime grain trade from the Black Sea region to Venice and other Mediterranean harbours relied on socio-economic structures developed over a century, and yet, was a direct response to large-scale famine due to cold and wet climate conditions between 1345 and 1347 CE.

The onset of the second plague pandemic should be understood as a rare coincidence of natural and societal circumstances, including volcanically forced and climate-induced changes in long-distance maritime grain imports as a unique pathway of plague-infected fleas. Although restricted to the 1340s CE, our study offers a possible mechanism to describe subsequent plague re-introductions into Mediterranean harbours17. More interdisciplinary research is, however, needed to understand if reoccurring plague outbreaks in Europe between the mid-14th and early-19th century were facilitated by long-distance maritime grain imports or other pathways. Priority in paleoclimatic research should be given to the assessment of high-resolution temperature and precipitation reconstructions from inner Eurasia, because it is still unclear if climate-induced variability in the functioning and productivity of ecological systems has affected the dynamics of natural reservoirs of Yersinia pestis and the likelihood of the bacterium to spill over into domestic mammals and eventually even into human populations. From a historical perspective, it is most important to improve knowledge about, and the resolution of, records of past plague outbreaks, as well as spatiotemporal changes in pre-modern, short- to long-distance cereal trade to connect the dispersal of the plague bacterium with zoonosis.

Although the coincidence of different environmental and societal factors at the onset of the Black Death seems rare, the probability of zoonotic infectious diseases to emerge and translate into pandemics is likely to increase in both, a globalised and warmer world. With the recent impact of COVID-19 in mind, it is obvious that the assurance and improvement of societal resilience require holistic approaches to address and tackle the wide spectrum of health risks58,59,60.