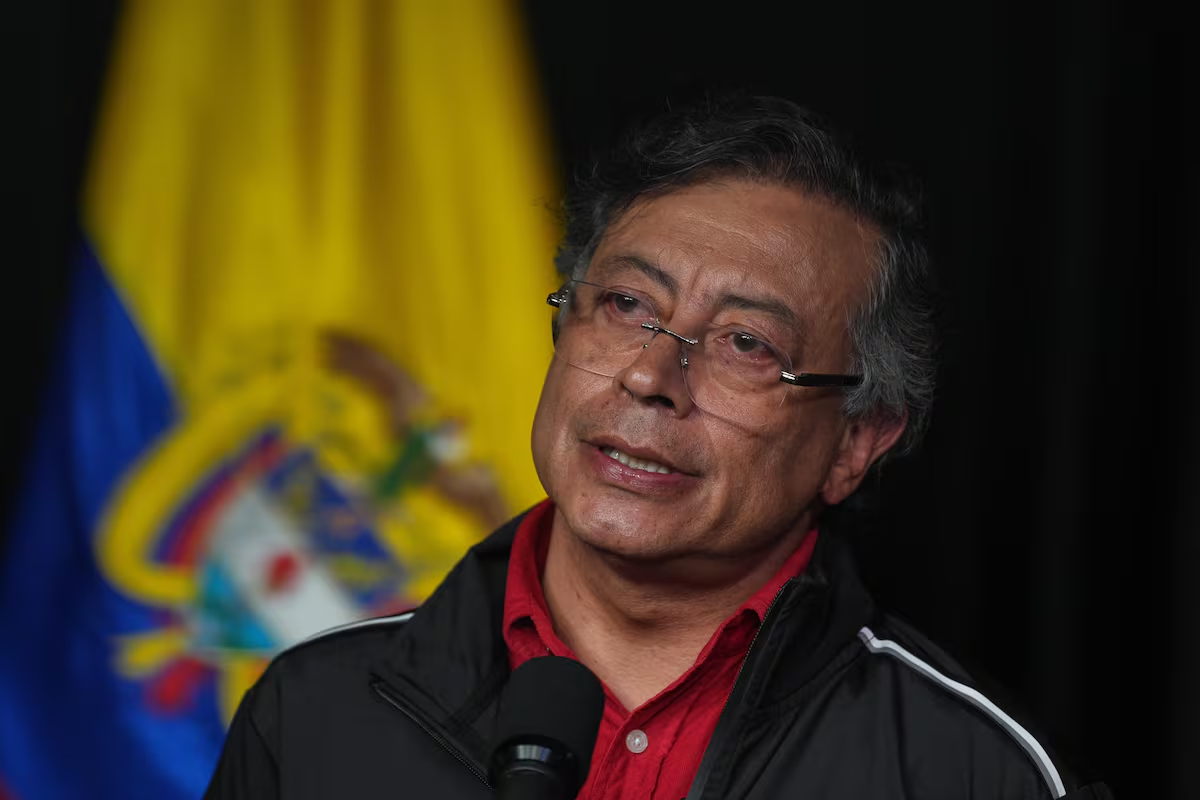

Petro and Trump, on the brink of disaster: ‘Attacking our sovereignty is declaring war’

‘Do not threaten our sovereignty, because you will awaken the jaguar,’ wrote Gustavo Petro, the leftist president of Colombia, on Tuesday afternoon in response to statements made by U.S. President Donald Trump. Minutes earlier, the American president had specifically mentioned Colombia among the countries he might attack to curb drug trafficking. “I hear Colombia, the country of Colombia, is making cocaine. They have cocaine manufacturing plants, OK, and then they sell us their cocaine… Anybody that’s doing that and selling it into our country is subject to attack,” the Republican leader said Tuesday in a conversation with the press, after concluding his last Cabinet meeting of 2025.

“Attacking our sovereignty is declaring war; do not damage two centuries of diplomatic relations,” the Colombian president responded on X, inviting Trump to come to Colombia to witness the daily destruction of cocaine labs. The exchange marks a new point of high tension in an increasingly deteriorating bilateral relationship.

Trump’s offensive in the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, where the world’s leading cocaine producer has coastlines, has already resulted in over 80 deaths. Although Operation Southern Spear has ceased its military attacks against boats accused of transporting drugs, the Trump administration has attributed this to its own success and indicated that this intensified war on drugs will now enter a new phase. “If we have to, we’ll attack on land. We’re taking those sons of a bitches out,” he said, in a threat that extended to the country governed by Petro and demonstrates the level of interventionism now defended, at least in rhetoric and specifically targeting Latin America, by a president whose first term was characterized by isolationism.

And he is doing so not only against a dictatorial regime like Venezuela’s, but even against a democracy like Colombia’s. This is something that Petro, proud to be what he calls the first left-wing president elected by his compatriots, sees as a major affront, one that dwarfs the string of previous clashes between the continental superpower and the leader of the country that for decades was its greatest ally in South America.

The background is significant. The initial clash over Petro’s refusal to accept a plane carrying chained migrants deported by Trump, which escalated into a declaration of trade war that was resolved within hours thanks to Colombian concessions, was merely a prelude. After a few months of relative calm during which the Republican leader focused on his tariff policies and on seeking peace deals in Gaza and Ukraine, the issue of drugs reignited tensions in September, when the U.S. government denied Colombia certification in the fight against drugs for the first time in three decades.

The decision was not merely a sign of displeasure, but a direct criticism of the Colombian president: “The failure of Colombia to meet its drug control obligations over the past year rests solely with its political leadership,” reads the White House memo. “I didn’t foresee that political power in the U.S. would fall into the hands of friends of politicians allied with paramilitaries,” Petro responded, in a harsh remark that, while rhetorically powerful, had little practical effect.

The clashes, however, have moved to more practical matters. In another display of rhetoric, just 11 days after the decertification, Petro took advantage of his visit to New York for the UN General Assembly to participate in a street rally against the war in Gaza. He took the floor and asked American soldiers to disobey Trump on any order to attack the Palestinians, and this earned him a decisive action: the U.S. government revoked his visa. Petro said he didn’t need the document, but the situation didn’t end there.

In mid-October, Trump labeled him a “an illegal drug leader” who promotes mass drug production, and his administration announced the end of payments and aid to Colombia, raising the specter of new tariffs. Petro was undeterred. “I will not concede, I will demand. Colombia has already conceded everything; it doesn’t have to concede any more,” he said in an interview with the journalist Daniel Coronell. “We have words, crowds, and a people ready to fight,” he affirmed, in another of his rhetorical responses to Trump’s measures.

Then came a photo from a White House meeting showing an image of President Gustavo Petro in a prison uniform, which led to a brief diplomatic clash, quickly defused, and Petro’s criticism of Trump’s statement about considering Venezuelan airspace to be “closed in its entirety.” The clash only intensified as the U.S. escalated its psychological warfare against the Nicolás Maduro regime. Trump’s threat of attacks in Colombia, and Petro’s response, took the verbal escalation to the point of belligerent insinuations.

Nothing suggests this is a genuine consideration. The armed forces and police of the two countries have a decades-long history of collaboration, primarily at technical and operational levels rather than political ones; the United States benefits from Colombia’s fight against drugs; and Colombia considers the United States its main trading partner. But the two leaders reinforce their rhetoric by criticizing each other, and thus benefit from the friction. However, the asymmetry is clear. Petro is marginal in the eyes of the U.S. president, who, nevertheless, has taken concrete measures and could take more. The Colombian president, for his part, is at the height of the election season and talking about a figure known to all Colombians, one who has a negative image according to local polls. The risk is that, in doing so, he is toying with a Trump who has shown no fear of making decisions that could harm Colombia.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition