The United Arab Emirates: From Footnote to Sophisticated Global Partner

In addition, the UAE has demonstrated skill in executing ambitious initiatives. The relatively small size of the Emirates—with around 1 million citizens versus about 25 million in Saudi Arabia—and its head start on diversification and development mean the challenges of domestic governance are a fraction of those of Saudi Arabia.20

National Debate

The UAE has little open debate about foreign policy and security issues. In part, these issues are widely understood as a prerogative of the country’s leadership, and any challenge or scrutiny can be taken as a sign of disloyalty. In part, too, the nation has what one Emirati political scientist has described as a “deep reservoir of goodwill” that the leadership has developed over more than five decades of maintaining security amidst startling economic development.21 Abu Dhabi’s first paved road came to be in 1961 (within living memory of at least some Emiratis), and the country’s leaders—not least the country’s founder, Sheikh Zayed—are credited with wisdom and foresight that have redounded to the people’s benefit.22 In a regional survey of attitudes published in 2020, a full 100 percent of young Emiratis approved of the government’s handling of the Covid-19 pandemic.23 It remains unclear, though, how much of that reflects government performance and how much reflects reluctance to criticize government performance.

Even so, Emiratis pay attention to the world, and they have views about what is happening around them. According to some polls, about a third supported the UAE’s normalization of relations with Israel, a third were neutral, and a third were quietly opposed.24 Since the outbreak of war in Gaza in October 2023, opinion has reportedly shifted to be sharply more critical of Israel and sympathetic toward Palestinians.25 Perhaps unsurprisingly, there seems to be no widely published public opinion polling on the issue; one must glean this sense through social media posts and a clearly expanded set of boundaries for public debate. In addition, the UAE government has been among the most active Arab governments providing humanitarian relief for Palestinians in Gaza, and it used its final months on the UN Security Council to call for an immediate ceasefire.26 The government has been clear, however, that it will not reverse normalization with Israel; therefore, few Emiratis are willing to call for it.27

Economics

Unlike many of its oil-rich neighbors, the UAE has two economic engines rather than just one. Oil fuels much of Abu Dhabi’s wealth, and Abu Dhabi is by far the largest energy producer of the country’s seven emirates.28 With proven reserves of about 100 billion barrels, the UAE exported $95 billion worth of petroleum in 2022 based on a production of just over three million barrels per day.29 While those numbers are not the highest in the world, they are among the highest per capita. For example, Saudi Arabia’s production capacity is about four times that of the UAE, but Saudi Arabia’s oil wealth is spread to about 25 million citizens, compared to the UAE’s 1 million.30 Abu Dhabi led the creation of the UAE in 1971 with a promise to share its oil wealth with other members of the confederation, and it has.31 Still, Abu Dhabi and its ruling family sit on a remarkable concentration of wealth, and they deploy it domestically and around the world in a strategic fashion.

The ruling family has deployed its wealth to a considerable degree in Dubai, just 100 kilometers up the coast. Dubai was an entrepôt when Abu Dhabi was a backwater, and financing from Abu Dhabi helped supercharge Dubai’s growth into a global trading hub. Dubai began attracting international investment in the 1950s, and it began aggressively developing infrastructure in the 1960s. Still, Abu Dhabi’s spectacular economic growth, beginning in the 1970s, combined with Sheikh Zayed’s interest in using largesse to cement ties between the individual emirates, meant Dubai enjoyed privileged access to capital for decades.32 This access was sometimes acute, such as when Abu Dhabi executed a $10 billion rescue of a Dubai real estate developer during the 2008 financial crisis.33 More often, though, Dubai represented a consistently attractive target for domestic investment at a time when Abu Dhabi had tremendous excess capital.

The business of Dubai has been more than mere trade, however. Dubai’s real value was exposed when the emirate emerged as a regional services hub in the 1990s and 2000s and fortunes were made developing real estate for commercial enterprises and housing. More than 3.5 million people now live in Dubai, perhaps 3.4 million of whom are expatriates.34 Emirati companies control land, construction, and imports, not to mention the logistics that link Dubai to the world. As Dubai’s growth has exploded, so too has the wealth of its rulers and Emiratis more broadly. While some wealthier expatriates live in Dubai and commute to jobs in other emirates, moderate-income expatriates live in adjoining emirates and commute to Dubai, spreading the benefits of Dubai’s economic activity further.

The Dubai model has helped ensure the UAE economy is more diversified than other energy-producing neighbors. Instead of government sinecures serving as the principal driver of employment and economic security, trade and business have provided attractive opportunities for many Emiratis. In addition, Dubai’s success has inspired imitation in Abu Dhabi and other Emirates, as they have aggressively sought to provide an attractive business environment for international investors. The result has been that less than one-third of the UAE’s GDP comes from hydrocarbons, compared to about half of GDP in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.35

The UAE’s growing interest in being a global hub has led it to pursue ever-widening sets of diplomatic relationships. The leadership’s educational and cultural orientation has been toward the anglophone world for more than a century, while the country has simultaneously sought to highlight its Arab identity since independence, creating an ever-deepening web of ties around the world, some of which appear contradictory. For example, the UAE drew especially close to the United States in the mid-2000s, in part due to 9/11 and in part in reaction to U.S. concern that a Dubai company might soon manage six major U.S. ports.36 As Saudi Arabia came under criticism for tacitly supporting extremism, UAE leadership sought to differentiate itself from Saudi Arabia and dispel concerns that it was anything less than a full partner to the United States. UAE special forces were deployed alongside U.S. counterparts in Afghanistan, and the UAE worked closely with the United States to combat terrorist financing.37 At the same time, however, as U.S. concern over Iran’s proliferation activities accelerated, Dubai’s trade with Iran blossomed to more than $15 billion per year.38 The Iranian government claims that about 800,000 Iranians now live in the UAE, both providing a lifeline to a country the United States is trying to pressure through sanctions and an escape valve for Iranians seeking to escape economic despair and political repression.39

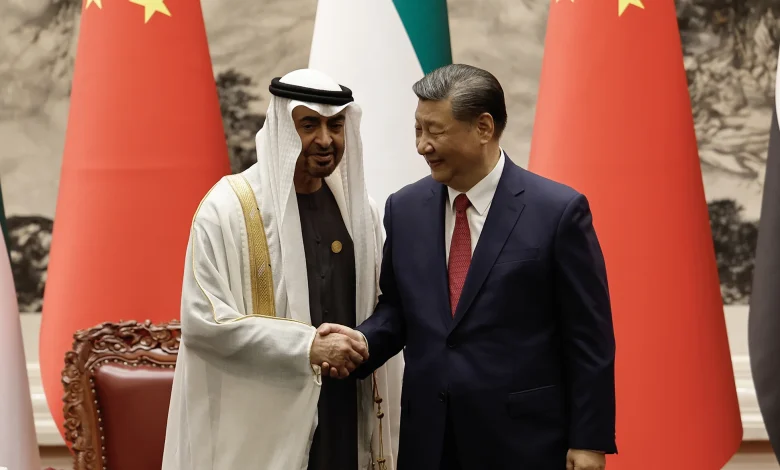

China’s ties with the UAE grew even more sharply, partly due to rising UAE oil sales to China and partly due to a growing interest in turning Dubai into a showroom for Chinese manufacturers selling to Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. That trade not only led to the creation of Dragon Mart—initially a mile-long mall crammed with Chinese wholesalers selling everything from consumer goods to industrial tools to heavy equipment, and now an even larger network of showrooms, hotels, and more—but it also bolstered Dubai’s container trade and helped drive traffic on Emirates, one of the two UAE national air carriers.40 Now, more than 400,000 Chinese live in the UAE, and a robust set of businesses provide services to the Chinese expatriate community while paying Emirati landlords.41 China struck a “comprehensive strategic partnership” with the UAE in 2018, putting the UAE in China’s first rank of international relationships, and trade exploded at a compound annual growth rate of almost 90 percent between 2017 and 2022.42

For many years, Russia played a marginal role in the UAE’s worldview. With relatively little trade, a modest security relationship, and differences over approaches to Iran, there was little cause for intimacy. The two sides shared common interests in places like Libya and Syria, where the Emiratis helped bankroll opposition to forces they identified as Islamist, and Russia’s Wagner Group fought them as well.43 The two leaderships were united in their hostility to any form of political Islam but not much else.

The Ukraine war and the subsequent efforts by Russians to find a haven for their assets drove a sharp rise in Russian immigration and investment. The UAE resolutely did not join U.S.-led efforts to isolate the Russian economy after the Ukraine invasion, and two years after the war began, Western countries were reportedly pressing the UAE to end the transshipment of dual-use materials that supported Russia’s war effort.44

Ties with India are also growing markedly closer. The UAE is home to about 4.3 million Indian expatriates, who outnumber the 1 million or so Emirati citizens in their own country.45 In addition, the UAE is closer to parts of India than it is to Kuwait, a fellow member of the GCC. But economic ties have been bursting, as trade and investment shoot up.46

As its economy and trade relationships have grown, the UAE has come to see itself as a genuinely global enterprise, connected not only to its traditional protectors in Europe, its new protector in North America, its former economic hubs in South Asia, and its growing customers in East Asia, but also to Africa, Australia, and beyond. The country does not fit into an East-West paradigm or a North-South paradigm. Instead, it links them, hosting large expatriate communities and even larger hordes of tourists in a post-nationalist, post-civilizational melting pot of coexistence and profit.

Great Power Competition

In the years immediately after its founding, the UAE did not think much about great power competition. Britain had been its traditional protector, and the United States filled the vacuum when Britain withdrew. Neither China nor the Soviet Union had much to offer. The UAE was serious about its Arab identity and advanced itself as a protector of Palestinian rights in a world that seemed to neglect them, but it did not seek to lead.

In the early twenty-first century, the UAE began to emerge from second-rank status. The two 9/11 hijackers from the UAE put additional scrutiny on the country. Many in the U.S. Congress objected on security grounds to Dubai Ports World acquiring the British shipping and logistics company P&O in 2006.47 The Emiratis concluded two things: First, they needed to be much more energetic in courting U.S. government support. To do this, they dispatched Yousef Al Otaiba, the key foreign policy aide to the then–Abu Dhabi crown prince (now the UAE president), as ambassador to Washington in 2008, where he has used his intimate connections to the UAE leadership to build trust with senior U.S. officials of both political parties ever since.48 In addition to fighting alongside U.S. troops in Afghanistan, the UAE has been deeply involved in counterterrorism efforts, including its efforts to be a regional hub for countering violent extremism. The UAE also became an important hub for U.S. military operations in Southwest Asia, hosting thousands of U.S. troops at Abu Dhabi’s Al Dhafra Air Base and hosting more U.S. Navy sailors’ visits at Dubai’s Jebel Ali than any other port outside the United States.49 Otaiba also played a key role in building UAE-Israel relations in the late 2010s, helping the UAE become a vital partner to the Trump administration and the catalyst for one of its signature foreign policy achievements, the Abraham Accords.

The second conclusion reached by the UAE was that it needed to broaden its strategic relationships to avoid overreliance on any one great power. While the UAE hews closely to the United States, it also has assiduously built its ties to China and Russia. One might argue that those ties represent a hedge against U.S. strategic abandonment, which UAE officials saw as a potential outcome after the Obama administration announced its strategic rebalancing toward Asia in 2012. These concerns intensified during U.S. negotiations over the Iranian nuclear agreement, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.50 Feeling that cleaving only to an increasingly distracted United States would be reckless, the UAE leadership sought to preserve its options.

But there were more reasons to widen the aperture of UAE ties: The Chinese expatriate community, mostly in Dubai, has been growing steadily, and UAE-China trade—now almost $100 billion per year—has been growing at an average of almost 25 percent per year since 2020.51 Dubai has emerged as a major logistics hub for Chinese trade to Africa, West Asia, and Europe, and Abu Dhabi has courted closer Chinese ties since the UAE was declared a comprehensive strategic partner in 2018. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Dubai aggressively sought to immunize its residents with the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, and Abu Dhabi created a deep partnership with the Chinese firm Sinopharm through clinical trials and manufacturing.52 Abu Dhabi also enlisted a Chinese firm for Covid-19 testing, which U.S. officials were concerned would leak DNA information to Chinese officials.53

Indeed, U.S. security concerns over Chinese involvement in the UAE have been rising. In 2021, U.S.-UAE talks over the sale of F-35 fighter jets stalled after the United States objected to the UAE’s purchase of a Huawei-built 5G telecommunications network, for fear that China would derive helpful signals intelligence about the plane’s electronic countermeasures.54 The jet sales were a principal driver of the Abraham Accords, so the UAE’s unwillingness to eschew a Huawei telecommunications system to obtain them indicates its commitment to strategic dynamism. Similarly, the United States objected vigorously to what it claimed was a Chinese effort to build a military facility at Khalifa Port in Abu Dhabi in late 2021, and leaked U.S. government documents in the spring of 2023 assessed that construction had recently resumed.55

Although the UAE has more recently claimed to be “decoupling” from Chinese technology firms, there are still questions regarding the depth of this shift. Emirati AI development company Group 42 (G42) has reportedly removed $1.7–$2.0 billion worth of Huawei hardware from its data centers as part of efforts to comply with U.S. export controls and court U.S. technology partners like Microsoft. Yet some observers note that Chinese authorities have remained unusually silent in response to these removals, which suggests that they might have an agreement in place. Moreover, other Emirati entities such as the state-owned telecommunications company e& (formerly Etisalat) continue to collaborate openly with Huawei on 5G and cloud infrastructure while simultaneously partnering with Microsoft and Amazon Web Services. This strategy is further complicated by revelations that G42’s divested Chinese holdings may have simply been transferred to another Abu Dhabi-based investment fund, Lunate, which remains under the supervision of the UAE’s national security adviser and retains major investments in Chinese tech firms.56 The UAE seeks to assure Washington of its commitment to AI-related decoupling, but ultimately, Huawei’s lingering footprint in Emirati infrastructure will continue to be a cause for U.S. concern.

While UAE-Russia ties do not match those between the UAE and China, they are robust and growing. The two major oil producers share an interest in managing global energy markets, and while Saudi-Russian ties (and tensions) have garnered most of the headlines, Abu Dhabi maintains a strong dialogue with Moscow on energy issues. The UAE has been a major purchaser of Russian weapons systems since the 1990s, and the UAE and Russia found themselves similarly aligned on a range of regional security issues, including their hostility to the strains of political Islam unleashed by the Arab Spring. Russian investments—which some experts have argued represent mere money laundering—have flooded into Dubai, and the influx only increased after Western powers imposed sanctions on Russia after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.57 Rather than join in solidarity with Western powers to isolate Russia, MBZ has put himself forward as a mediator between Russia and Ukraine, helping negotiate at least six prisoner swaps between the two sides.58

The UAE has an advantage in demonstrating that it has alternatives to the United States, and calling out what it sees as onerous conditions in agreements, in order to drive better bargains. Yet, as the UAE has witnessed in some of its agreements over technology and weapons sales, the United States limits its crown jewels to its closest partners. The UAE must constantly balance the costs and benefits of being a close partner with the United States against the benefits that Russia and China offer for creating more distance with the United States.

Emirati officials profess an interest in building ties in every direction rather than joining one bloc instead of another. Anwar Gargash, former UAE minister of state for foreign affairs and current adviser to the UAE president, argued in 2021, “We’re all worried, very much, by a looming Cold War. . . . The idea of choosing is problematic in the international system, and I think this is not going to be an easy ride.”59 He expressed similar sentiments in 2023, arguing at a conference in St. Petersburg, Russia, “This polarization has to be broken.”60