Why Dhurandhar Has Exposed The Fault Lines Of Film Criticism

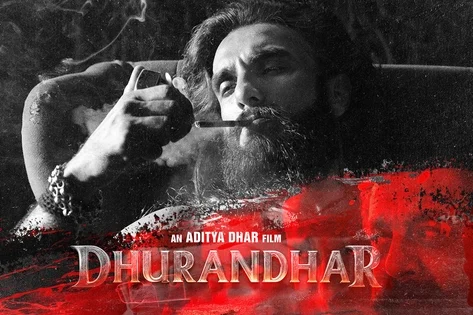

There is a distinct sense of déjà vu unfolding in the editorial pages, Twitter threads and Insta reels/clips of India’s film critics this week. The subject of their ire is Dhurandhar, the new high-octane action drama helmed by Aditya Dhar and starring Ranveer Singh. While the box office numbers suggest the film being off to a good start at the theatres, the critical establishment appears to have worked itself into a knot. The reviews are shrill, bordering on the frantic, painting a picture of a movie that is not just bad art, but moral transgression.

The chargesheet against Dhurandhar is long. It is accused of being ‘over the top,’ ‘crude,’ and, most damningly in the eyes of the jury, ‘propaganda masquerading as cinema.’

To a neutral observer, the collective hyperventilation may be startling. But to anyone observing the landscape from Tamil Nadu, this sudden allergy to political messaging in cinema is not just amusing. It is historically illiterate.

The propaganda paradox

The primary accusation levelled against the espionage drama is that it is an ideological vehicle. One cannot help but pause and chuckle at the timing of this epiphany. To cry wolf over ‘messaging’ in Indian cinema in 2025 is roughly 75 years too late.

In Tamil Nadu, the intertwining of celluloid and politics is not a bug, it is the operating system. The Dravidian movement was among the first political ideologies in the world to successfully cotton on to the fact that cinema is a potent vehicle for mass communication. Long before social media algorithms, it was the silver screen that drove their ideas. (Even the freedom fighters of the pre-independence era understood the utility of the medium to carry their lofty messages).

The point is, for decades, films have been used to shape public consciousness. When critics today clutch their pearls because a Bollywood film pushes a specific nationalistic narrative, they reveal a childish naivete.

The ‘crude’ double standard

Another arrow in the critic’s quiver is the claim that Dhurandhar is crude and lacks nuance. This argument, too, withers under the slightest scrutiny of recent cinematic history. Consider the critical reception of Viduthalai Part 2, released just last year.

Directed by Vetrimaran, a darling of the festival circuit and the Left-leaning intelligentsia, the film was an unabashed, full-throated campaign for Naxalite ideology. It painted its world in broad, unsparing strokes, and nuance was sacrificed at the altar of revolutionary zeal. It was, for all intents and purposes, as propagandist as a leaflet distributed at a party cadre meeting.

Yet, the reception could not have been more different. Viduthalai (both parts) was celebrated at film festivals and lauded for its ‘bravery’ and ‘raw power.’ The violence was deemed ‘visceral,’ not ‘gratuitous’. The lack of subtlety was called ‘uncompromising,’ not ‘crude.’

This disparity in critics’ reception proves that crudeness is not a disqualifier for acclaim. If the political text of the film suits their palate, broad strokes are hailed as masterpieces. When the text shifts to another ideology, similar narrative techniques are suddenly dismissed as cinematic malpractice.

The reality of the enemy

Perhaps the most peculiar criticism of Dhurandhar is the discomfort regarding its antagonists. Critics seem aghast that the film makes no bones about naming Pakistan and Islamic terrorists as the enemy. The reviews treat this as a dangerous new phenomenon, a post-2014 invention designed to polarise.

Again, as a Tamil film viewer, these hot takes are baffling. This is, after all, the land of ‘Captain’ Vijayakanth. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, Vijayakanth built an entire career (and eventually a relatively successful political party) on the back of movies where he played the unstoppable patriot. Whether as a cop, an army man, or a spy, his mission was singular. That is, annihilate terrorists from Pakistan.

In those films, the nationality and religion of the villains were never ambiguous. They were spelled out in rousing, thunderous dialogues that drew whistles at cinema halls across the state. This wasn’t seen as hate speech. It was taken in stride as a reflection of the geopolitical reality of the time. Critics back then had no bone to pick with those flicks. They understood them as commercial entertainers mirroring the anxieties of the nation. Why, then, is a similar portrayal in Dhurandhar treated almost as a violation of the Geneva Convention?

Fact, fiction, and skulduggery

Then we arrive at the intellectual arguments. They allege Dhurandhar claims to be fiction but manipulates real events to ram home its point. This is presented as a uniquely unethical tactic.

In reality, this is the oldest trick in the Kollywood playbook, and one that has recently been employed by films celebrated by the very same critics now tearing down Aditya Dhar.

Take the case of Soorarai Pottru (2020), starring Suriya. The film was based on the life of GR Gopinath, the founder of Air Deccan. In real life, Gopinath is an Iyengar. Yet, the film stripped him of his Brahmin identity and recast him as a EVR-following crusader. It was a flagrant mix of fact and fiction designed to suit the Dravidian narrative. The critics? They sang paeans to the film’s ‘authenticity’ and ‘heart’, and the film won five National Awards.

Similarly, in Jai Bhim (2021), another Suriya starrer based on a real-life case of police brutality against an Irular tribe member, the filmmakers tweaked reality again. The real-life police officer responsible for the atrocity was a Christian. In the movie, his character was signalled to be a Vanniyar, a change that sparked significant political friction. This was political skulduggery of the highest order, distorting facts to target a specific community.

Or even more recently, Amaran (2024), the bio-pic on Major Mukundh Varadharajan. Here too, the protagonist’s caste (Brahmin) was blurred as it would be too unpalatable for the Dravidian Tamils. Facts are tweaked to make it acceptable for the public.

Where was the outrage then? Where were the dissertations on the ethics of ‘bio-pics? The silence was deafening. It appears that twisting facts is acceptable creative liberty, provided the twist leans in the ‘correct’ political direction.

The crumbling gatekeepers

Underpinning all this critical angst is a sense of lost authority. Critics complain of being targeted by ‘trolls’ on social media, lamenting that no one is standing up for them. But this claim to victimhood rings hollow.

Trolls are always shrill and unfiltered. But not all who take down these critics are trolls. To label them all so is just convenient narrative setting. The bigger reality is that critics are not in national service. They are not owed protection or deference. Their complaint sounds less like a plea for safety and more like entitled moaning from a class of gatekeepers who have realised the train has left the station. The audience no longer needs a mediator to tell them what to watch.

A shift in cinematic competence

For years, ‘patriotic’ cinema was often synonymous with jingoistic clunkiness. But recent releases, including last month’s Netflix release Baramullah, suggest a shift. Going by the grudging admissions of the critics themselves, these films are technically proficient, well-acted, and visually compelling. They are catching up to the production standards that the Left itself had mainstreamed over decades.

In that sense, the Left is being hoisted on its own petard. They established the rules of the game, that cinema is a valid tool for ideology. Now that the other side is playing the game effectively, the referees are crying foul.

It is nobody’s case that Dhurandhar is above criticism. No art is perfect. But the criticism should be about pacing, lighting, screenplay, and performance. When the criticism morphs into moral policing about the politics of the film (while giving a free pass to identical politics on the other side of the spectrum), it loses its legitimacy.

The critics have long dished out a standard line to those offended by controversial films. “If you don’t like it, don’t watch it.” It is time they swallowed their own pill. You cannot demand freedom of expression for the art you like and demand censorship, in a manner of speaking, for the art you despise.

To borrow a sentiment from Tamil Nadu, what is blood for one set cannot be mere thakkali (tomato) chutney for another. If a film works, it works. Its message is for the audience to accept or reject.

The gatekeepers can step aside.