The future will be wearable

Ask Max Donelan what he’s been up to this year and he’ll show you the machines: industrial sewing machines, machines that can print electronics onto fabric, specialized treadmills that measure foot impact, motion-capture camera systems, big fans for a wind tunnel – the list goes on.

But at the centre of it all is a machine made of flesh and blood.

“The whole question is, how do you effectively work with the human body?” said Dr. Donelan, a professor of biomedical physiology and kinesiology at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, B.C. When you’re creating technology to help the body achieve something, he explained, the tech is always “the least complicated partner in the marriage.”

It’s a guiding principle for WearTech Labs, a newly opened facility spread across the SFU campus that businesses can gain access to for a fee or through partnerships. They can then develop and test wearable technologies with human subjects, while drawing on an array of equipment and scientific expertise to speed the process.

The $17-million project, half funded by federal and provincial grants and half by SFU, had its official ribbon cutting earlier this month. But it builds on a history of working with industry that Dr. Donelan and the project’s co-leader, Ed Park, have cultivated for years.

Open this photo in gallery:

WearTech Labs scientific director Max Donelan, a professor of biomedical physiology and kinesiology at Simon Fraser University.Jennifer Gauthier/The Globe and Mail

“We want to see breakthroughs in wearables, so that those wearables are used in clinics, workplaces and homes,” said Dr. Park, a professor of mechatronics and robotics at SFU. “And we want to help Canadian companies build world-class devices that are used by our public.”

Taken together, the labs form a unique research complex for rapid prototyping and analysis that looks equal parts science experiment, textile factory and gym.

“There are bits of this that exist everywhere,” Dr. Donelan said during a walk-through earlier this year. What makes the project exceptional is “this tight integration of the human science side with the technology side.”

For Dr. Donelan, who earned his PhD in biomechanics from the University of California, Berkeley, and whose academic interests lie at the crossroads of physics and phys. ed., the new facility is the realization of a long-standing dream.

But its arrival now seems particularly well timed. As a recent federal report on the state of science and technology in Canada made clear last month, an anemic level of research and development activity across the country’s business sector is a critical problem that drags down productivity and, ultimately, Canadians’ standard of living. WearTech Labs offers a model for private-public collaboration that is consciously set up to work on industry questions at industry speed.

And the facility is coming online just as consumer demand for wearable technology is ripe for acceleration for a host of reasons, including advancements in materials and AI, plus increased concerns with health and mobility in an aging population.

Lindsay Housman, founder and chief executive of Hettas, a Vancouver-based company that makes high-performance running shoes for women, said the philosophy embedded in WearTech Labs is precisely what she needed when she launched the start-up in 2023.

She said she got the idea for Hettas when she took up the sport in her 40s and experienced the pain and discomfort that comes from wearing running shoes that are ostensibly made for women but are actually miniaturized versions of men’s footwear – a product-design approach known as “shrink it and pink it.”

“When we were batting around this idea of what would we do differently if we created shoes specifically for women, one of the first things that came to mind is we wanted it to be research-based,” Ms. Housman said.

Open this photo in gallery:

Technical project manager and research scientist Ray Tran works with student Ellie Thompson in the motion capture lab.

The challenge was the scarcity of data on how women’s feet change as they age, and how bones, ligaments and muscles respond to shifting hormone levels, pregnancy and other sex-specific variables.

When Ms. Housman discovered what was possible at SFU, she became a client and a collaborator. Working with Chris Napier, a running-science expert and assistant professor of physical therapy, Hettas commissioned a literature review and supported focus group studies of both recreational and competitive female runners. The results, published in October in the journal BMJ Open Sport and Exercise Medicine, point the way to future work that could yield improved shoe design based on sex, life stages and other factors.

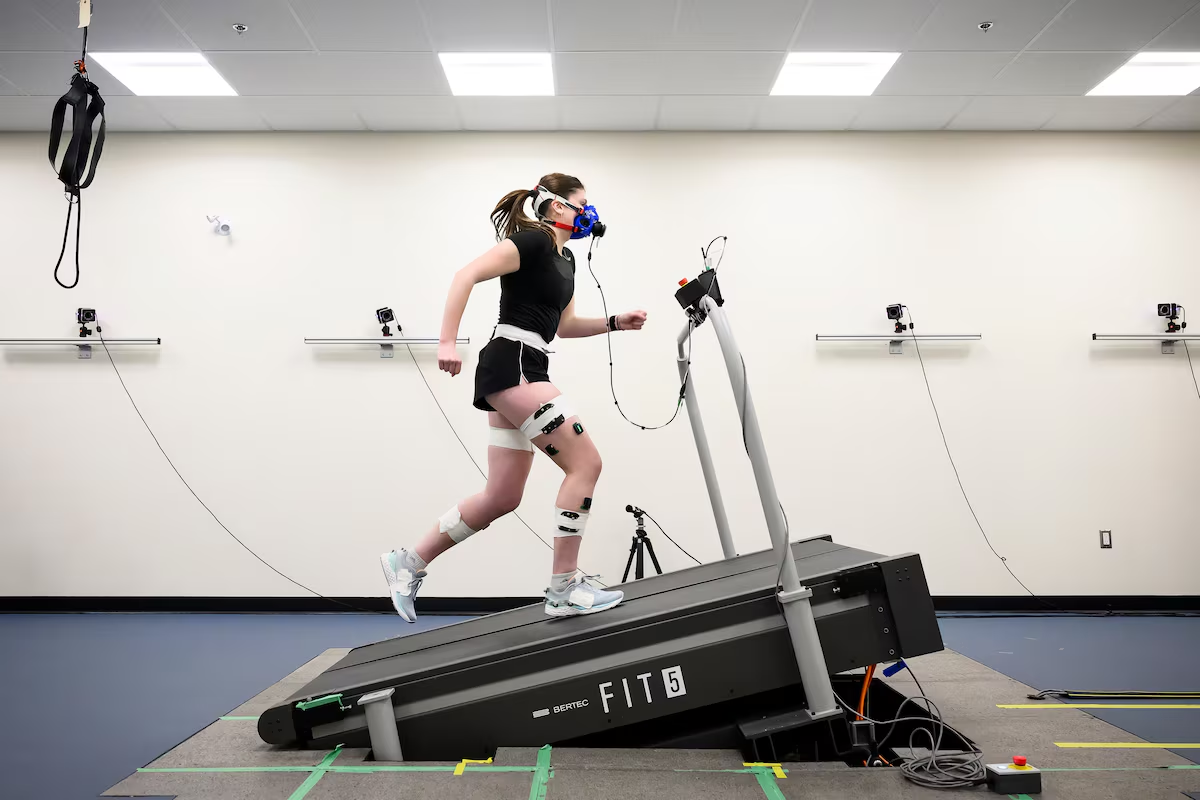

The company has also worked with Dr. Napier on mechanical studies to reveal the force profile on women’s feet and legs as they run. More recent research examined the effect of the menstrual cycle on the biomechanics of running, and Ms. Housman said Hettas is looking into the feasibility of wearable technology that tracks hormones in order to reduce the likelihood of injury.

The research work, she said, has been “incredible” for the company, not just for the hard science it has provided but also because of the response it’s garnered on social media.

“Women really want this information. So I think that’s really important.”

Open this photo in gallery:

Dr. Donelan visits installation engineer Jon Cooke inside the lab’s wind tunnel. Once completed, the wind tunnel will be used to conduct performance tests of wearable gear for cyclists.

Those not immersed in clothing and equipment manufacturing may be surprised at what can be accomplished now with computer-guided machinery. WearTech Labs has tapped into this revolution and is equipped to whip up garments with all manner of embedded devices for testing.

The facility also includes environmental rooms where people and wearables can be subjected to extreme heat and cold, or to reduced oxygen levels as might be experienced when climbing at high altitude. A wind tunnel, still under construction, can be used for controlled studies of how gear performs when worn by a cyclist moving at racing speed.

Perhaps the most important environment – particularly for health-related technologies – is the sleep room, for testing wearables designed to gather data while subjects snooze.

What researchers at SFU have created is the ability to turn concepts into prototypes that can efficiently demonstrate what works and what doesn’t, said Daniel Ferris, a professor of biomedical engineering at the University of Florida’s Human Neuromechanics Laboratory in Gainesville. He visited WearTech Labs earlier this year.

“They have a lot of capabilities that would be hard to match,” said Dr. Ferris, adding that even if he could find commercial contractors to do similar work, the cost would be prohibitive.

One area where WearTech Labs is well positioned to make a difference is in helping create and test devices for wearable health monitoring. Many medical professionals are skeptical about the accuracy and usefulness of some current popular devices that consumers use to monitor basic data such as heart rate and body temperature.

Dr. Ferris said it would be a boon to personalized medicine and health care if more sophisticated and easy-to-use monitors could be developed to track a wider array of vital signs with clinical reliability. Sometimes physical changes can be correlated with mental health, which could improve response and care strategies for those in distress.

“Working with WearTech Labs,” Dr. Ferris said, “we could fabricate prototypes and validate their metrics compared to gold standard research devices.”

Open this photo in gallery:

Mr. Larimi works with samples to be examined with the lab’s scanning electron microscope.

Dr. Donelan said he has learned a lot in his years of exploring the science of motion and how that knowledge can be turned into beneficial technologies. Some of his research involves the use of exoskeletons – mechanical devices that move with patients and can help them to stand up and walk on their own. Both he and his co-lead, Dr. Park, have been involved in spinoff companies that make exoskeletons for people with movement challenges.

What those experiences have demonstrated is that a research idea typically needs to be carried a long way before a company can successfully pick it up and run with it. If wearable technology is going to become an important and widespread element in our lives – and if Canada wants to derive an economic return from it – there will need to be a lot of validation and testing.

Dr. Donelan said WearTech Labs is designed to make that possible, and to help companies develop the knowledge they need to understand what they are creating.

For businesses looking to enter the wearables arena, especially start-ups, “you’re going to need to work with someone to do it,” he said. “You could find some labs, academic research labs to do it, but they wouldn’t be used to working with companies. So the people who find us – they’re excited.”