Rob Reiner knew how to listen to people

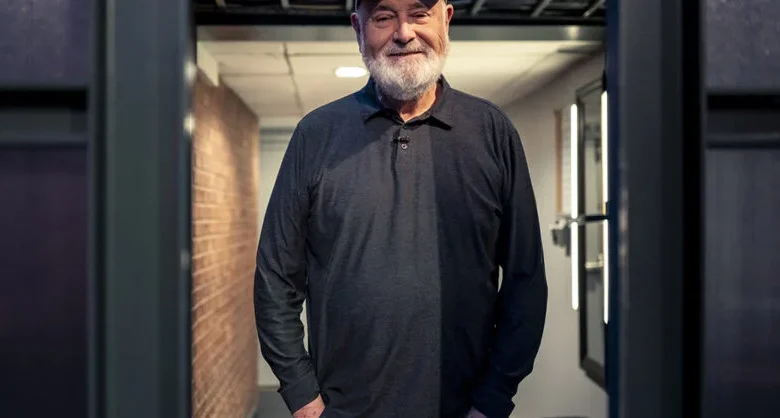

Photo by Lloyd Bishop / NBC via Getty Images

I always imagined that Rob Reiner would be someone I’d want in my life. Not as a hero or an icon, but as a friend – the kind of person whose presence makes things feel a little easier. There was something about him, in his face as much as in his films, that suggested curiosity and ease, but also a wit that carried real delight in people and their absurdities. Rather than reaching for obvious punchlines, his humour often emerged through tone, timing and restraint, trusting moments to land without being pushed. That quality came through not only in the films he made, but in the ones he appeared in too, where he often seemed happiest listening, reacting, letting the moment do the work.

Rob Reiner’s death, reported in circumstances that are still hard to take in, sits awkwardly alongside the memory many of us carry of a filmmaker whose work consistently resisted hardness or cynicism. It’s hard to make the two sit together. So the films are where I find myself looking, not as a way of summing him up or reaching for conclusions, but because they feel like the most familiar way of approaching him.

Reiner’s films were never flashy in their intelligence, and they didn’t insist on being admired. They were attentive to how people talk when they are not quite saying what they mean, to how relationships shift over time, to how humour often sits very close to vulnerability. What I notice most is how carefully they seem to listen to people.

When Harry Met Sally is usually described as a romantic comedy, but it has always felt more cumulative than that. It seems less interested in romance as an event than in what happens over time, in how opinions harden and soften, how certainty gives way to compromise, how intimacy is built through repetition rather than revelation. It is funny because it notices familiar truths, and moving because it avoids grand gestures in favour of small recognitions. What still strikes me is how closely it tracks the rhythms of adult life, and how little that attentiveness seems to date.

Treat yourself or a friend this Christmas to a New Statesman subscription for just £2

Scenes in the film were given time to breathe. Conversations were allowed to wander. Jokes often arrived sideways, emerging out of character rather than out of structure. Whole stretches hinged on timing and interruption, on lines thrown away rather than underlined. In This Is Spinal Tap, the humour built through repetition and escalation, the joke deepening because it was never fully announced. Meaning was not pointed out; it was allowed to surface. Watching them again, you realise how much is happening in the gaps.

Moving across Reiner’s films, what emerges is not just range, but a particular kind of understanding behind it. Stand by Me captures childhood without nostalgia, alert to its cruelties as well as its loyalties. Misery is taut and controlled, unsettling without being showy. The Princess Bride manages to be playful without condescension, trusting its audience to understand irony without flattening wonder. Taken together, these shifts in tone suggest a filmmaker who was comfortable moving between worlds because he understood that people themselves are rarely one thing at a time.

This Is Spinal Tap is often talked about for its influence, and rightly so, but what feels most striking on repeat viewing is its generosity. The film is sharply funny, but its satire is directed as much at the machinery around the band as at the band themselves, and it never withdraws sympathy from them. There is space for foolishness without contempt, and that instinct feels revealing.

I’ve spent years returning to both When Harry Met Sally and This Is Spinal Tap, and they’ve never felt exhausted by familiarity. Each time, something new presents itself, often quietly, sometimes unexpectedly. They are films packed with moments that have entered the culture, lines and scenes people return to again and again, yet what gives them their staying power is something broader, a way of observing people over time. Reiner appeared to trust that audiences would grow, and that the films could grow with them. That confidence, both in the material and in the viewer, feels like a mark of generosity, and perhaps of curiosity too.

Faced with news that resists easy understanding, there is a temptation to rush towards explanation. Reiner’s films suggest a slower response. To sit with them. To notice what continues to open up over time. They remain attentive, generous, and alive to contradiction, still offering something back to anyone willing to return. That feels like enough, for now.

[Further reading: Sentimental Value is an extraordinary investigation into generational trauma]