One of America’s Most Iconic Early Religious Cults Is Brought to Life in a Beautiful New Movie. But Did They Really Dance … Like That?

The perfect tagline for The Testament of Ann Lee might be “If you’re going to see only one musical about the early Shakers, make it this one.” However, this highly idiosyncratic film is not really a musical in the conventional sense, with the dramatic action punctuated by characters expressing their emotions in song, often accompanied by choreographed dance numbers. TTOAL is more of a docudrama, with dramatized scenes linked together by narration that conveys the factual context (leading it to sometimes resemble an illustrated lecture). The songs are adaptations (by composer Daniel Blumberg) of Shaker hymns that are used to express not so much the feelings of individual characters as to re-create the communal mystical experience of Shaker worship, which is based on movement and song.

The film is co-written and directed by Mona Fastvold, producer of The Brutalist, and, as in that film, the beautiful buildings—the barns and meeting houses of surviving Shaker villages that exemplify the tradition’s guiding values of simplicity, utility, and working with nature—threaten to steal the show. Interiors aficionados may find themselves distracted by the lovely handcrafted chairs, chests, and tables (the Shaker communities were renowned for their woodworking), but the Shakers themselves would no doubt be disconcerted to discover their legacy lies more in kitchen design than in the network of egalitarian, pacifist utopias they were hoping to establish across the United States.

It explains a lot about modern-day America to understand that from its earliest days as a colony, the nascent country was a quilt of various Protestant sects ranging from patriarchal conservatives to what we would recognize as feminist socialists (not that they would have called themselves that), with the Calvinists/Puritans based in Massachusetts, the Quakers in Pennsylvania (after the Puritans drove them out of Massachusetts—apparently the religious freedom the Calvinists moved in search of did not extend to denominations they disapproved of), and the Mennonites in the Midwest. What they had in common was “the priesthood of all believers,” which asserts that all believers can approach God directly without the intercession of a priestly caste, and a belief in the virtue of hard work and an agrarian existence apart from the corruption of the cities.

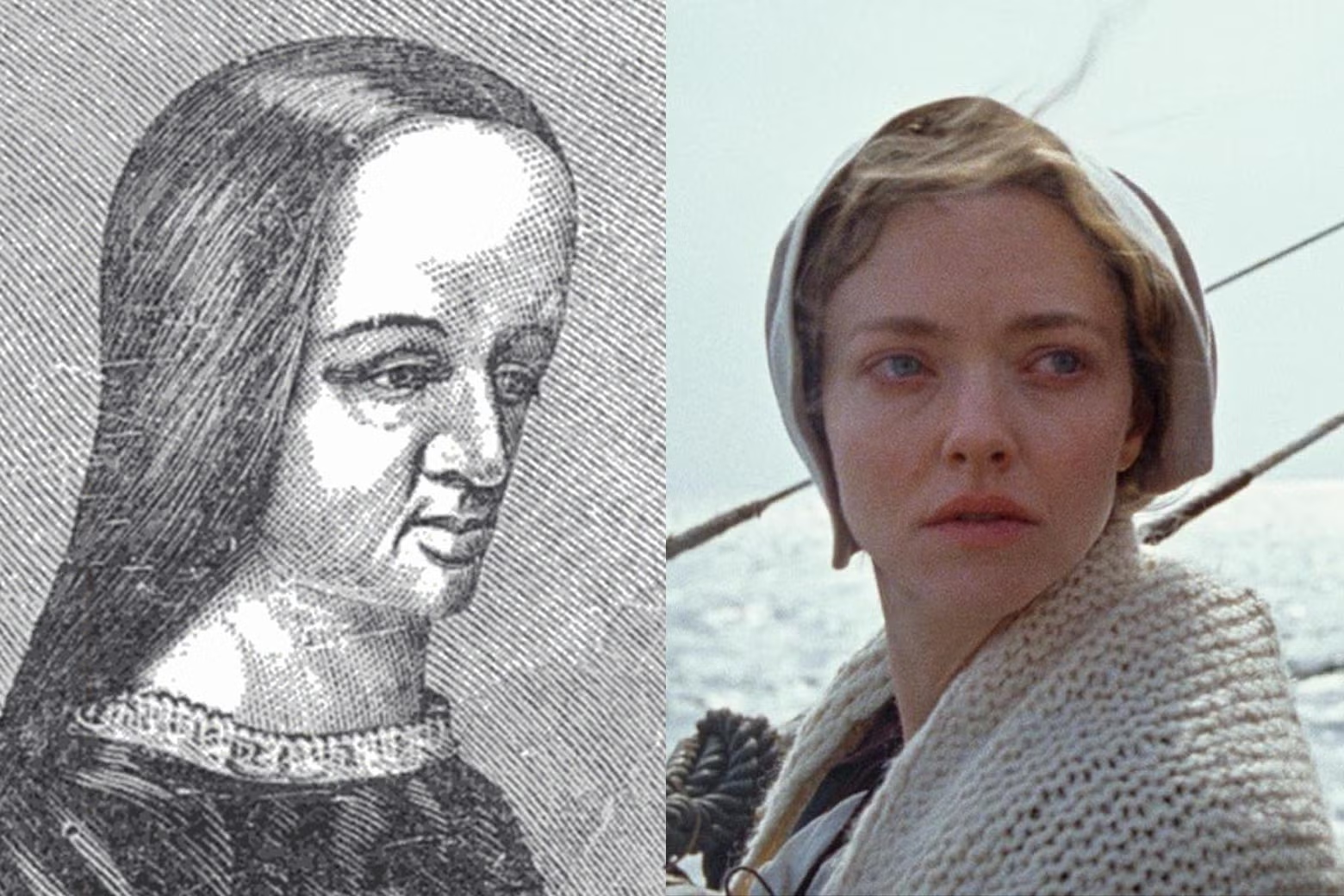

The film is a “speculative retelling,” as Fastvold put it, of the life of Ann Lee, the founder of the Shakers. Considered by many of her followers to be the “female Christ,” Lee, like the original, did not leave any contemporaneous record of her teachings. The “testimony” that forms the basis of the Shakers’ beliefs was written down some 30 years after her death and no documentation of her life exists before that. Nevertheless, based on what is known about Lee’s life, we look at what’s fact and what’s fiction in The Testament of Ann Lee.

Did Lee Advocate Celibacy in (and out of) Marriage?

After the death of her fourth child in infancy, Ann has a breakdown and is admitted to an asylum. While there, she decides she wants to renounce sex. After she is released, she starts preaching at Shaker meetings in Manchester. When the neighbors, disturbed by the grunts and cries coming from the Shaker service, call the police to break it up, Ann is taken off to jail. In prison, she goes on a hunger strike and has a vision of Adam and Eve being expelled from the Garden of Eden, which leads her to attribute their separation from God as arising from fornication. After she is released, she preaches that Shakers must adopt celibacy.

This is true. Shaker histories date Lee’s revelation that celibacy was necessary for a holy life and a way to reunite the believer’s spirit with God to a period of imprisonment in Manchester in 1770. She never condemned marriage and did not forbid married couples from joining the Shakers (although she was considering it when she died), but she did insist they did not engage in marital relations. (Lee herself had been married to a blacksmith, but he left her after the move to America.)

Without offspring, the Shakers had to attract recruits, so missionary work became important and, as the film shows, Lee, her brother William, and other senior members of the community traveled to nearby settlements to spread the word. (The Shakers were also known for taking in foundlings, orphans, and vagrants. Similar to the Amish tradition of allowing their young people to experience the wider world in their late teens before choosing to either be baptized into the church or leave permanently, Shaker adoptees were given the option to leave the community and join the world outside when they were 21.)

All this brings to mind yet another of those American sects, although one that didn’t appear until the 19th century: the Mormons, who also set off on a long journey to an unknown land after their leader, Joseph Smith, had a vision (a small contingent of eight Shakers sailed from Liverpool in 1774 based on a vision that had appeared to Lee urging her to found a colony in North America), who regularly sent out missionaries to convert new members, and who had unusual views on domestic arrangements that led to their being considered a bit weird and suspect.

Lewis Pullman as William Lee in The Testament of Ann Lee

Searchlight Pictures

Did the Shaker Service Involve Choreographed Dancing?

While working as a cook at a Manchester infirmary (a rudimentary local hospital), Ann hears about revival meetings featuring a woman preacher. With some trepidation, she attends a meeting of the Wardley Society at the home of a tailor and his wife, John and Jane Wardley (Stacy Martin), known as the “Shaking Quakers.” The congregants believe that when Jesus comes back, it will be in the form of a woman, so women are permitted to speak far more than is usual. The other tenets of the Wardley Society include the importance of confessing your sins to God and the centrality of ecstatic dancing. This involves worshippers writhing and falling to the ground accompanied by wailing, grunting, and outbursts of glossolalia, or speaking in tongues. There are also group dances where the congregation moves as one.

This is all true. The Wardleys’ Shaking Quakers split from the regular Quakers in 1747, although they retained the mainstream group’s commitment to pacifism and equal rights. While living in London, the Wardleys had been influenced by a group of exiled French Protestants called the French Prophets, or, as they were known in their native mountains of southern France, Camisards.

The Camisards were a group of Occitan-speaking peasants and craftsmen—largely, like Ann Lee herself, illiterate—who in the 17th century started a guerrilla uprising against the French. But they were motivated by religion, not politics. They believed they could speak directly with God through their prophesying without the intercession of the church (like the Catholics) or the guidance of scripture (like the Calvinists), and that this spiritually empowered state was revealed by shaking, falling to the floor, and speaking in tongues.

Prophesies from the mouth of women and children carried particular weight (this last tenet the French authorities found especially subversive, and some half a million Camisards were killed or exiled). The influence of the Camisards may be at the root of the Shakers’ insistence that the governance of their communities should be divided between men and women and their belief that when Christ returned, it would be as a woman. However, Lee never claimed she was the Second Coming, although this was a claim made for her by some of her followers in an 1808 document designed to codify Shaker beliefs.

Ann Lee did indeed start attending meetings of the “Shaking Quakers” at the Wardleys’ home in 1758. Jane Wardley acted as mother of the sect, hearing believers’ confessions, a role Ann Lee increasingly assumed after her visions in 1770 when the group started calling her “Mother” Lee, and continued in the U.S.

When the Quakers were founded in 1652 as the Society of Friends, their services originally incorporated violent trembling, hence their more informal name. But in the 1740s, the denomination moved toward a more sedate form of worship where members of the congregation spoke and observed periods of silence without further physical activity. However, spontaneous dancing was part of Shaker worship until the early 1800s, when it was replaced by structured, choreographed routines (so the organized movements shown in the film would not yet have been in use when Ann Lee was in Manchester).

Rather than the film’s sweeping movements that suggest the Shakers were more familiar with the work of avant-garde choreographer Pina Bausch than the Holy Ghost Dance, the Shakers’ group dances involved a slow and laborious series of movements often incorporating rigid holding and sudden releases, designed to help the spiritual overcome the physical and promote discipline and union within the community. Dancing as a form of spontaneous spiritual release returned around the 1840s, but by the end of the 19th century the Shakers had returned to a more sedate Quaker-like model, with services consisting of hymns, testimonials, a short homily, and silence.

Was Ann Lee Fatally Beaten?

At first, the Shakers are left to get on with building their community near Albany, New York, in peace, even though pamphlets appear accusing the sect of encouraging women to strip naked in the woods and of being controlled by a spirit of witchcraft. However, there is no official suppression, although trouble arises with the authorities when Ann discourages her followers from fighting in the war of independence, saying they won’t pick up arms. Soon, an Army general appears with a loyalty oath for her to sign. Citing her pacifist beliefs, Ann refuses and is arrested, but then released after an influential Shaker gets the governor of New York to intercede.

Nadira Goffe

It’s Impossible to Talk About One of Our Most Controversial Cultural Figures. This Documentary Encapsulates Why.

Read More

But worse is to come when she, William, and their associate James Whittaker go to visit one of the six new settlements the Shakers have established in New England. They are in the middle of a service in the settlement’s meeting hall when it is set on fire by a group of local vigilantes alerted by the characteristic wailing and groaning. William, pacifist as he is, urges the Shakers not to fight back. William, James, and the narrator, Mary, are detained and beaten to within an inch of their lives, but not before some thugs lift Ann’s skirts in public to determine if she is really a woman. Although he makes it back to the settlement, William dies of his injuries. Ann, severely injured, lasts for a few months longer before she too succumbs.

-

One of America’s Most Iconic Early Religious Cults Is Brought to Life in a Beautiful New Movie. But Did They Really Dance … Like That?

This is largely true. Opinion is divided as to whether Lee died of a fractured skull received during the worst beating or from the cumulative toll of being attacked by violent mobs as she and William traveled around in search of new members. A violent crowd in Petersham, Massachusetts, dragged Ann from her horse, threw her into a sleigh, and stripped her of her clothes to prove she was not a man (unlike Seyfried, the real Lee was tall and imposing). In 1780, other unfriendly locals savagely abused Ann and some Shaker elders, accusing them of being British spies based on their refusal to fight before they were imprisoned in Albany. However, the usual objection to the Shakers was the rumor that they were keeping women who wanted to go back to their families imprisoned against their will and, of course, the allegations of witchcraft.

An account from 1816 tells of a large mob of 400 people that attacked a group of Shakers in 1783 as they worshipped in Harvard, Massachusetts, burning the building they were in and driving the Shakers out of town, warning them never to return. When the Shakers gathered to pray under an elm tree, the mob attacked again.