See the cutting-edge FIFA World Cup turf research happening at University of Tennessee

University of Tennessee’s turf research for the 2026 FIFA World Cup

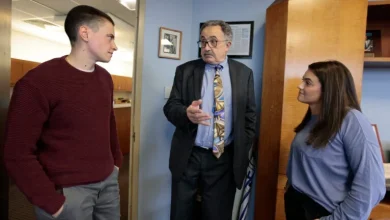

John Sorochan, professor of turfgrass science and management at University of Tennessee, explains the process of working with FIFA on playing pitches.

Sixteen stadiums across the United States, Canada and Mexico will host the FIFA World Cup in 2026, and the University of Tennessee at Knoxville is leading the research to ensure turf quality is pristine and consistent across all 104 matches next summer.

John Sorochan, a distinguished professor of turfgrass sciences and management at UT, said the university is in the “11th hour” of research as his team of faculty members, technicians and students prepare for the ultimate test after putting their work into practice earlier this year at the Club World Cup.

Sorochan, who’s collaborating with Michigan State University, joined Knox News on an exclusive tour at the East Tennessee AgResearch and Education Center-Plant Sciences Unit, where FIFA has built a covered facility to replicate the conditions of five domed stadiums hosting the 2025 FIFA World Cup between June 11 and July 19.

SCROLL THROUGH PHOTOS BELOW AND READ THEIR CAPTIONS FOR THE FULL STORY

Growing sod on plastic lets it develop roots, allowing UT and the growers to easily roll up the sod and place it in stadiums faster. This reduces stress on the grass and keeps growers from cutting the roots. Artificial fibers make up about 5% of the sod and provide stability as the grass grows, and each sod plot is about 2 inches thick. When combined with other technology to create a “shallow pitch,” the sod can be assembled and disassembled in under 12 hours both ways. “We’ve come up with something that you can put in a temporary surface and still play at the highest quality level,” Sorochan said.

UT uses LED grow lights to simulate how turf will grow inside the five domed stadiums in Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, Los Angeles and Vancouver. Sorochan and his team have tested how long the lights need to be shining − about 12 hours for a full field − and when they need to be turned on. The color of lighting is important, as various color wavelengths produce varying levels of energy. Blue sends out more energy in shorter waves to produce short, sturdy growth, while red is used as a stimulus whose longer waves help grass grow lusher.

Sorochan and research associate Kyley Dickson developed the fLEX machine after an NFL game set for Mexico City had to be relocated in 2018 because the field was deemed unsafe. Sorochan returned from the experience annoyed but inspired to find a way to test fields based on how athletes will come into contact with the ground while playing, including how cleats affect turf. “We developed a machine that would simulate a foot strike,” he said. “I gave the charge to Kyley, and we sat and brainstormed over what would it need to look like and do all that. And we engineered a foot that would strike the surface to measure the compliance of the surface. We put all sorts of sensors in it.” Sorochan used fLEX in the FIFA research, and several NFL teams now benefit from the technology. He sold the machine earlier this year to SGL System, a Norwegian company that develops grow lights.

Sorochan points out how his team took warm-season Bermuda grass and overseeded it with cool-season ryegrass, allowing the ryegrass to sprout up and act as a stabilizer − similar to how artificial fibers are used in the sod grown on plastic. UT found success using Bermuda grass for the Club World Cup and plans to use it again for the 2026 FIFA World Cup in specific climates, though most soccer pitches are Kentucky Bluegrass. Michigan State University, FIFA and UT will inform teams about the varying playing surfaces throughout the tournament, Sorochan said.

Dillon McCallum, lead technician for the FIFA research, was working for a country club when he showed an interest in turf. His boss pointed him to Sorochan, and McCallum arrived at UT to study for his master’s degree in turfgrass pathology. “If I could have told myself sophomore year of college that I was going to be working on a project that was helping assist the organization in putting on the FIFA World Cup, I would have said, ‘That’s crazy’ and ‘That sounds perfect,'” he said.

When Sorochan, UT and FIFA install the turf at stadiums, they have a couple of options: the shallow pitch, left, or the slightly elevated one atop six inches of sand shown to the right. There’s a layer of a geotextile fabric called Permavoid underneath that manages how water drains from the turf. For the shallow pitch, this layer gives grass the room sand would normally provide. Extra sand will be used for stadiums that require irrigation systems and sprinkler heads to run throughout the field. Turf at Neyland Stadium, for comparison, sits on about one foot of sand, Sorochan said.

Jumping on the turf is fun, sure, but it also illustrates the real reason behind the research − to make the playing surface feel consistent for players no matter where they’re playing during the FIFA World Cup. If you were to jump on the different types of turf at UT like I did, you wouldn’t be able to tell a difference between them. The consistency is important for player safety, but it also ensures athletes are able to compete at the highest level − and on a level playing field − by minimizing outside factors like torn-up turf. This is why FIFA brought in UT to help with the World Cup and why they plan to keep working together in years to come.

Keenan Thomas is the higher education reporter for Knox News. Email keenan.thomas@knoxnews.com.

Support strong local journalism by subscribing to subscribe.knoxnews.com.