O.J. Simpson Estate Claim: What His Case Reveals About Civil Judgments After Death

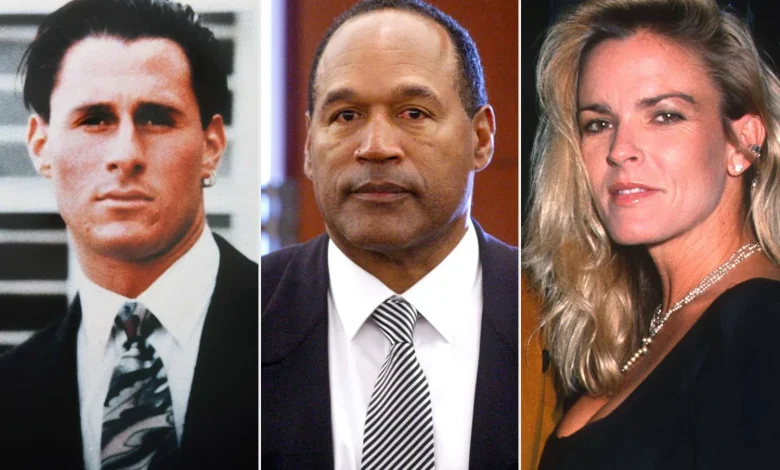

News about O.J. Simpson’s estate accepting a long-standing claim from the family of Ron Goldman has sparked a question many people never think about until a well-known name brings it into focus: what really happens to a civil judgment when the person who owes it dies?

Simpson’s case may draw the headlines, but the underlying issue is something probate courts handle every week. All over the United States, families learn—often at the worst possible moment—that an estate can become the final stop for unpaid court judgments, federal and state tax claims, and long-dormant civil awards. For many people, this part of the legal system is unfamiliar until a high-profile dispute shows how persistent a judgment can be.

Seen from that perspective, the renewed attention offers something useful: a chance to understand how probate law, estate debt rules, and long-term civil judgments actually work in practice.

Civil Judgments Don’t End at Death — They Shift Into the Probate Process

One of the biggest public misconceptions is that debts and judgments simply “disappear” when a person dies. They don’t. Under every U.S. probate system—whether a state follows its own code or versions of the Uniform Probate Code (UPC)—most legally enforceable obligations become claims against the estate.

The process is procedural and predictable:

-

A probate court appoints an executor or personal representative.

-

That executor must notify known creditors and publish public notice for unknown ones.

-

Creditors then have a fixed window—often a few months—to file formal claims.

-

The court reviews each submission and decides whether to accept or reject it.

Wrongful-death judgments, such as the civil judgment obtained by the Goldman family, are treated exactly like other civil awards. Once approved, they join the estate’s liabilities and are resolved according to state law.

This is why lawyers often describe probate as the final “accounting period” of a person’s life: the legal responsibility continues, even if the individual does not.

Why Older Judgments Balloon: Post-Judgment Interest Explained

One of the most surprising things for the public is the size of long-running civil judgments. The increase is not unique to this case; it is the outcome of a very ordinary legal mechanism: post-judgment interest.

States calculate this interest differently—some base it on federal rates, others on a statutory percentage—but the principle is consistent:

-

interest accrues each year,

-

it continues until the debt is paid,

-

and it is designed to ensure a judgment remains meaningful even if years pass.

Legal scholars often note that interest serves two distinct functions. It compensates the judgment creditor for lost time and discourages debtors from delaying payment in hopes the obligation will fade. Over 20 or 30 years, that interest can easily eclipse the amount originally awarded.

For anyone concerned about civil judgment enforcement, this explains why a decades-old judgment may look so much larger today—it has been growing the entire time.

How Probate Decides Who Gets Paid First: Understanding Creditor Priority

Probate doesn’t pay creditors on a first-come, first-served basis. Instead, every state applies a legally defined priority system that determines who gets paid and when. This structure is one of the least visible but most important parts of estate administration.

While the exact order varies, many states follow a hierarchy similar to the UPC:

-

Administrative expenses (court fees, executor expenses)

-

Federal tax obligations, including IRS claims

-

State taxes

-

Secured creditors (such as mortgages or car loans)

-

Judgment creditors

-

Unsecured creditors

-

Heirs and beneficiaries

The result is often surprising: even a major civil judgment may sit behind tax authorities and administrative costs. The executor must follow this ranking precisely. If the estate doesn’t have enough assets to satisfy all approved claims, the unpaid portion does not transfer to heirs unless they were legally responsible for the original debt—which is rarely the case in wrongful-death matters.

This hierarchy is one reason probate can feel slow. It’s not designed for speed; it’s designed for orderly settlement.

When the Estate Falls Short: How Executives Locate, Value, and Recover Assets

Another area often misunderstood is just how active an executor must be when managing an estate that owes money. Their role is not simply to distribute belongings—it is to protect, identify, and assemble the estate’s assets before any distribution occurs.

This can involve:

-

searching for property the deceased owned,

-

obtaining professional valuations,

-

selling assets through public auctions or private sales,

-

reviewing past financial transfers,

-

and, where necessary, initiating legal action to recover estate property.

Many states also have statutes addressing fraudulent transfers, which allow executors to ask a court to look at transactions made shortly before someone’s death if those transfers appear designed to place assets beyond creditor reach. Courts examine timing, intent, and whether a transfer left the estate insolvent.

In estates with public interest or substantial debts, every item can matter—vehicles, memorabilia, intellectual property rights, or even smaller collectibles. Probate law requires the executor to pursue these assets within the limits of state law, even if doing so involves additional legal steps.

Why Probate Takes Time — And Why Headlines Rarely Tell the Full Story

Highly publicised developments can make probate appear unpredictable, but the process is largely controlled by statute and court oversight. What feels like “slow progress” is often the system functioning exactly as intended.

Several factors contribute to the pace:

-

Creditors must be given legally required notice.

-

The executor must review and respond to each claim.

-

Courts evaluate contested claims and may require hearings or supporting documentation.

-

Tax authorities conduct their own reviews.

-

Assets cannot simply be sold; they must be valued, marketed, and transferred in a transparent way.

Legal experts frequently emphasise that probate prioritises accuracy and compliance over speed. This is especially true when the estate involves significant debts, a high-profile individual, or complex assets.

For families, the process can feel like a long coda to a much longer story. Legally, however, it is the final stage of ensuring that obligations are handled in a manner consistent with state law.

Looking Ahead: Why High-Profile Cases Shape Public Understanding of Judgment Enforcement

When public figures are involved, probate disputes shine a rare spotlight on an otherwise procedural area of law. They clarify several realities many people never encounter until faced with an estate themselves:

-

Civil accountability can continue after death.

-

Estate debts follow strict legal rules and timeframes.

-

Probate courts exist to ensure fairness to creditors, not only heirs.

-

Long-standing judgments can be enforced decades later.

These cases often inspire a broader conversation about how civil judgments are enforced, how estates are evaluated, and what happens when debts intersect with limited assets.

As proceedings develop in any high-visibility estate, attention inevitably shifts from the celebrity involved to the larger legal questions: How should long-overdue judgments be resolved? What protections do creditors have? How do families navigate probate when major debts are in play?

Those questions—not the headlines—are the ones that will likely matter most in the months ahead.

FAQs on O.J. Simpson’s Estate and Judgment Claims

How long can a civil judgment remain enforceable?

States vary widely, but many allow judgments to be renewed periodically—often every 5, 10, or 20 years—making them enforceable long-term if properly renewed.

Do heirs inherit debts?

Generally, no. While an estate may owe money, heirs only become personally responsible for a debt if they were legal co-obligors.

Can an executor challenge transfers made before death?

Yes, in certain circumstances. Many states have fraudulent-transfer laws that allow courts to examine transactions that may have been intended to hinder creditors.

Can personal property be sold to satisfy estate debts?

Yes. If items belong to the estate and are not protected by state exemptions, they may be sold as part of the probate process.

For readers interested in how inheritance rules differ internationally, Lawyer Monthly has also examined German-American probate procedures in detail.