Review: ‘Marty Supreme’ Is as Hollow as a Ping-Pong Ball

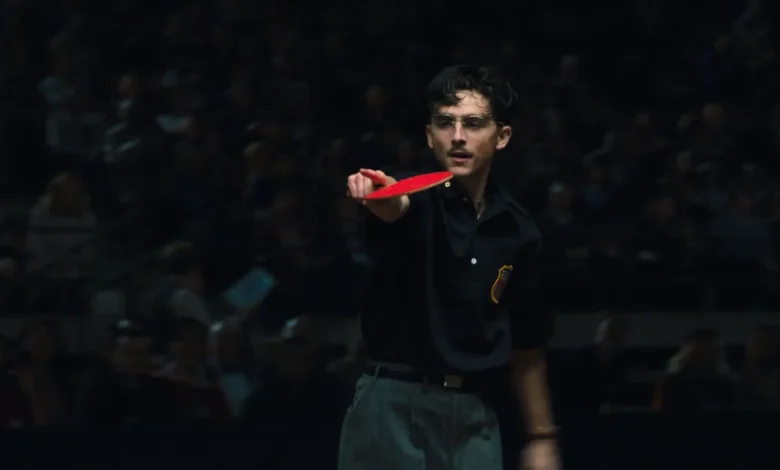

Mean-spiritedness lies in the eye of the beholder: one person’s aggressively sour-minded movie is another’s idea of delightfully jaundiced fun, and no movie this year proves that as aptly as Josh Safdie’s two-and-a-half-hour loop-de-loop character study Marty Supreme. Timothée Chalamet stars as the Marty of the title, a rising 1950s table-tennis star, who’s so driven to succeed he doesn’t care who gets trampled in his upward climb. Those he hurts and disappoints include, but are not limited to, his closest friend from childhood, Odessa A’zion’s Rachel, whom he knocks up and abandons; Kay Stone (Gwyneth Paltrow), a rich but rather sad 1930s movie star whom he seduces and steals from, though she’s so starved for attention that she comes back for more; his boss at a New York shoe store, Murray (Larry “Ratso” Sloman), from whom he also steals; and his mother, Rebecca (an underused Fran Drescher), who’s so ostensibly manipulative that we’re supposed to deduce that the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree—in other words, Marty can’t help being a user, it’s in his genes.

Marty Supreme is the kind of movie that’s often approvingly characterized as a “fun ride”; we’ve moved long past the era when movies could just be movies. It’s about as brash and peripatetic as Safdie’s last feature, 2019’s Uncut Gems, made with his brother Benny Safdie, but its undertones are nastier, and it’s somehow even more exhausting. Marty—who’s loosely based on a real-life 1950s table-tennis champ, though this story is fiction—is brazenly selfish, and the worse he behaves, the more we’re urged to applaud him. He’s supposed to be a complex character, but maybe he’s just an unbearable one.

The movie opens in 1952 on the Lower East Side. Jittery young Marty Mauser, a born hustler with a sleazy mustache and a Velveeta smile, has a job selling shoes, but not for long. He’s headed to London for an important international table-tennis match. His plan has been to work only until he’s earned his airfare, and that day has come. But before he finishes up the workday, he gets a visitor at the store: it’s Rachel, his oldest friend, pretending to be a customer. Rachel is married to a guy who doesn’t treat her right, Emory Cohen’s Ira, but Marty, it turns out, isn’t much of an improvement. He and Rachel zip to the stockroom where they have awkward sex: it might not be casual for her, but it is for him. The next thing we know, the movie’s credits are rolling, a graphic of a gaggle sperm eagerly competing for a single, alluring egg. It was funnier, and better, when Amy Heckerling did it in 1989, to kick off Look Who’s Talking, but never mind.

When Marty’s boss Murray refuses to give him the cash he’s earned, Marty steals it so he can get on that plane. As infractions go, this one is mild—he has earned the money—but it’s still a pretty accurate introduction to his wily unscrupulousness. Marty makes it to the London championships, but he loses in disgrace to an elegant Japanese player, Koto Endo (real-life player Koto Kawaguchi). He vows revenge, but first, he’s got to find a way to eventually get to Japan.

Gwyneth Paltrow as Kay Courtesy of A24

Meanwhile, upon his arrival in London, he’s gotten a gander at Paltrow’s Kay, who’s staying at his hotel. He rings her up from his room, standing on his bed in socks, underpants, and bathrobe; somehow, she falls for his bratty seduction techniques and later graciously gives him a diamond necklace to fund his exploits, just because. (Paltrow’s performance is the only one here that shows any real human warmth.) He also wheedles his way into the not-so-good graces of Kay’s husband, writing-implement czar Milton Rockwell (played, with embarrassing stiffness, by Canadian entrepreneur and rich guy Kevin O’Leary), who tries to lure Marty into a deal that’s too crooked even for him. There has to be one person in the Marty Supreme universe who’s more dishonorable than Marty is, and Rockwell’s stuck holding the short straw.

For Safdie, a movie seems to be just an excuse for a million and one digressions and distractions; he’ll throw anything at the wall to see if it sticks. Marty comes up with the idea of marketing red-orange pingpong balls instead of white ones; the scheme doesn’t pan out but is used later for a go-nowhere visual idea. A bathtub falls through the floor of a decrepit hotel, the kind of Looney Tunes detail designed to make you think, “Wow! Isn’t this crazy?” though it’s just business as usual in zany Marty Supreme. The competitive table-tennis scenes are adequate, shot and edited with a modicum of care, but it’s hard to have any stake in them—they’re almost like afterthoughts. Ugly behavior abounds: even Rachel participates in it, pulling off a nasty bit of deception that results in her oafish but not totally evil husband Ira getting bashed, bloodily, in the head. Through it all, we’re supposed to relish the emotional complexity of the story, or maybe even just its dark humor. Amorality can be fun, but Marty Supreme has no emotional core—though it does try to grab us in its final minutes, when Marty is unrealistically redeemed in a moment of mawkish sentimentality.

Meanwhile, Safdie works hard to wow us with a series of New Wave needledrops, including Tears for Fears’ “Change” and Alphaville’s “Forever Young.” Imagine! 1980s music in a movie set in the 1950s. Crazy, right? This is “Look at me!” filmmaking at its most exhausting. Safdie seems to like to collect big names, even when he’s not sure what to do with them, and he packs a bunch of them into this clown car of a movie. The production design, by the god-tier Jack Fisk, may be the best thing about the movie—Fisk is in tune with great ‘50s details like stockrooms filled with boxes or run-down, décor-crowded apartments where people have lived for years. But other filmmaking icons don’t fare as well: The picture was shot, in various tones of puddle-water and mud, by the previously great Darius Khondji (also the cinematographer on Uncut Gems). And there are so many performers cycling through Marty Supreme that few of them make any impression. Why couldn’t we have more of Drescher, or Tyler the Creator as Wally, Marty’s sometime righthand man, who’s as cool and breezy as Marty is high-strung? Essayist and novelist Pico Iyer has a small role, though the character he plays serves virtually no purpose in the plot. Nutball downtown legend and possible genius Abel Ferrara, as the thuggish Ezra Mishkin, appears as part of a stolen-dog subplot that’s never adequately resolved, though it does result in one minor character’s being blasted in the face with a shotgun—fun times.

Odessa A’zion as Rachel in Marty Supreme Courtesy of A24

At the center of this ungodly swirl of is Chalamet’s Marty, chasing after fame and fortune like a cartoon greyhound snapping at a mechanical rabbit. Characters don’t need to have redeeming qualities to be great; in fiction, at least, our most notable flaws can set us apart from the pack. Chalamet never does anything by half measures—he began training for this role in 2018, often traveling with portable table-tennis gear. As Marty, he’s suitably overcaffeinated and callous, and he knows how to make his eyes look as flat and cold as those of a dead fish on ice. He does everything the film asks of him.

Chalamet is an incredibly gifted performer, one who can do anything he turns his hand to, which means he should be more choosy, not less. Last year, he gave a fantastic performance as the young Bob Dylan, another guy known to be, at times, manipulative and selfish. But he also found the locus of Dylan’s charisma, and captured the elusive idea that Dylan’s brilliance as an artist amounts to a grudging generosity, a flame we long to creep close to for some very good reasons. His Marty Supreme performance, on the other hand, comes off as a thing he could do in his sleep, the result of research and dedication and all the things great actors like to do. It’s as flat as a ping-pong ball is round, and just as hollow, an empty sound bouncing nowhere and everywhere in the entropic movie around it.