Deadly outbreak silences Tyrnavos barns

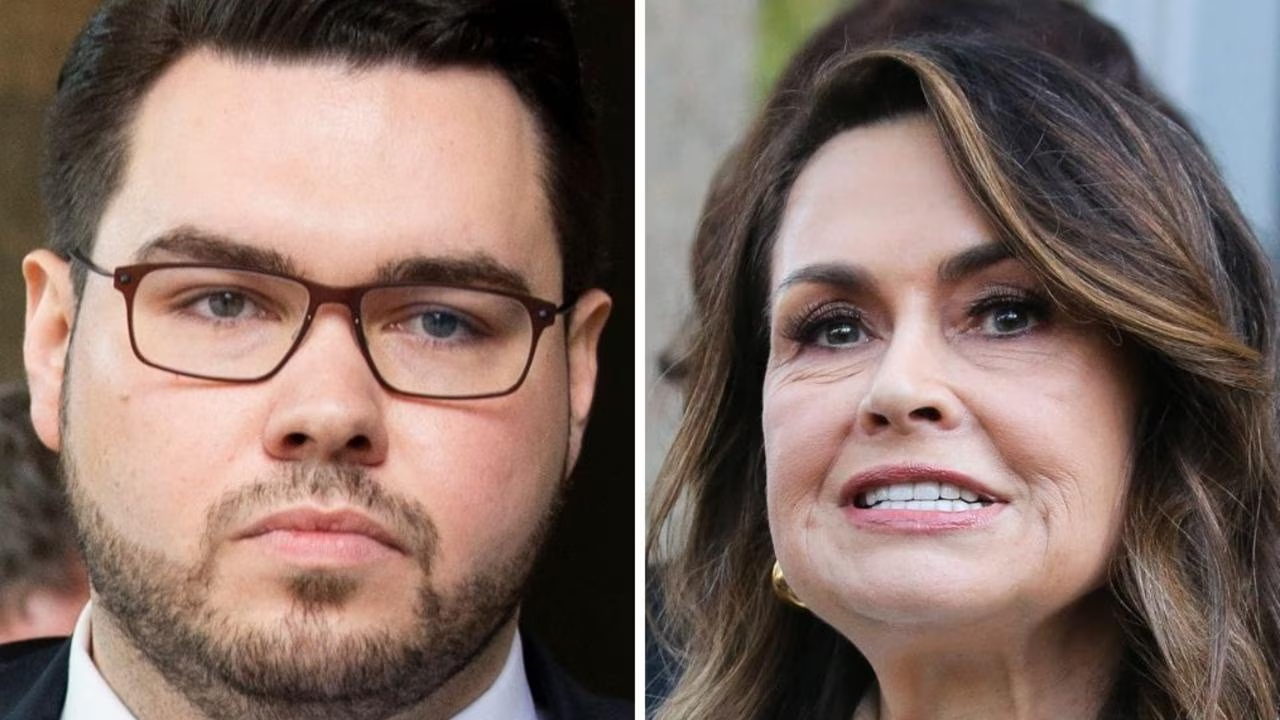

Giorgos Tasioulis has bags of fodder and no animals to give it to. His is one of several farms visited by Kathimerini in an area that has been battered by the ongoing sheep pox epidemic. [Alexandros Avramidis]

In the farm belt around the municipality of Tyrnavos, central Greece, the barns stand silent. Over just three months, from June to August, sheep and goat pox swept through herds that once produced milk for prized feta cheese. Entire flocks were culled, leaving fields empty and families reeling.

The crisis in Tyrnavos unfolds as Greece records a wider resurgence of the disease. In recent weeks, veterinary services have reported sharp spikes in four regions long considered “clean”: Serres, Achaia, Aitoloakarnania and Ilia. Serres has logged 166 cases since January, 150 after mid-September. Achaia recorded 155 total, 110 after early September. Aitoloakarnania has 90 cases, with infections turning double-digit weekly only after early November, while Ilia has counted 26, including 17 since mid-November. Officials warn that any relaxation of biosecurity – improper animal movements, missed precautions, insufficient disinfection – opens the door to new outbreaks.

At Kalamaki, Tasos Gargalas lost 700 animals. Across the old national road in Platykambos, Manolis Papakoikonomou saw 1,100 destroyed. Nearby, Vasilis Dimitriou lost 1,500, and Giorgos Tasioulis another 700. “Wherever you turn your eyes, there isn’t a single living sheep or goat. Only two dogs left,” Giorgos said.

More than 20 livestock farmers in the area have suffered the same fate. Some, for the first time in their lives, bought milk from a supermarket. Since losing their herds, the farmers say each phone call brings another bill – bank loans, feed suppliers, veterinarians, even rent for children studying in Thessaloniki. “First we eat, and then we pay whatever we can,” they say. With no animals left, many have joined farmer protests for the first time.

Their frustration runs deep. “They treat us like uncouth shepherds. They tell us, ‘You must become Europeans,’” one farmer said. “Well, the politicians and officials must become Europeans. We ask for help and they answer, ‘I don’t know.’”

Still, none plans to abandon the work of generations. Tasos remembers the June 6 diagnosis. “The vet looked at me and said, ‘You know what you must do.’ I saw my 78-year-old father crying like a child.”

The disease spread quickly. Vasilis’ herd was culled on June 20. Manolis’ unit was hit on August 8. “In the morning the newborns nursed; by night they were dead,” he said. His brother’s August 24 wedding was canceled. “No joy, no money – nothing.”