Sarah Jo Pender asks for mercy 25 years after double murder conviction

INDIANAPOLIS (Court TV) — Sarah Jo Pender, once dubbed “the female Charles Manson” by a prosecutor, stood before an Indiana judge in December, asking for a second chance at freedom 25 years after being convicted in a double murder that left two roommates dead.

Sarah Pender sits in court on Dec. 5, 2025, during a resentencing hearing. (Court TV)

Pender, now 45, delivered an emotional statement during her resentencing hearing, taking responsibility for her role in the 2000 deaths of Andrew Cataldi, 25, and Trisha Nordman, 26, while maintaining she was not the shooter.

“I’m so nervous. Today is one of the biggest days in my life. I’m asking to be free, not to die in prison,” Pender said, her voice shaking as she addressed Marion County Superior Court Judge James Snyder.

The Dec. 5 hearing featured testimony from family members, educators and a documentary filmmaker who painted a picture of transformation during Pender’s quarter-century behind bars, including five years spent in solitary confinement.

Pender was 21 when Cataldi and Nordman were shot to death in the Indianapolis home they shared with Pender and her then-boyfriend, Richard Hull. Hull, who admitted to being the shooter, took a plea deal and was sentenced to 75 years. Pender went to trial and was sentenced to 110 years: 50 years on one count and 60 on the other.

During the hearing, Pender described herself at 21 as “rudderless” and “adrift,” working a desk job after attending Purdue University for a year. She revealed she had been raped by a neighbor months before the murders, an assault that left her “paralyzed with fear” and clinging to anyone who made her feel safe. She met Hull shortly after the assault and he moved in with her a month later. He then invited his friends, Cataldi and Nordman, to move in with them. Three months later, Cataldi and Nordman were dead.

According to court records, the bodies were discovered on Oct. 30, 2000, in a dumpster behind the Teamsters Local Union on Meridian Street. Both had been shot with a 12-gauge shotgun. Nordman was shot in the chest with deer slugs; Cataldi was also shot in the chest.

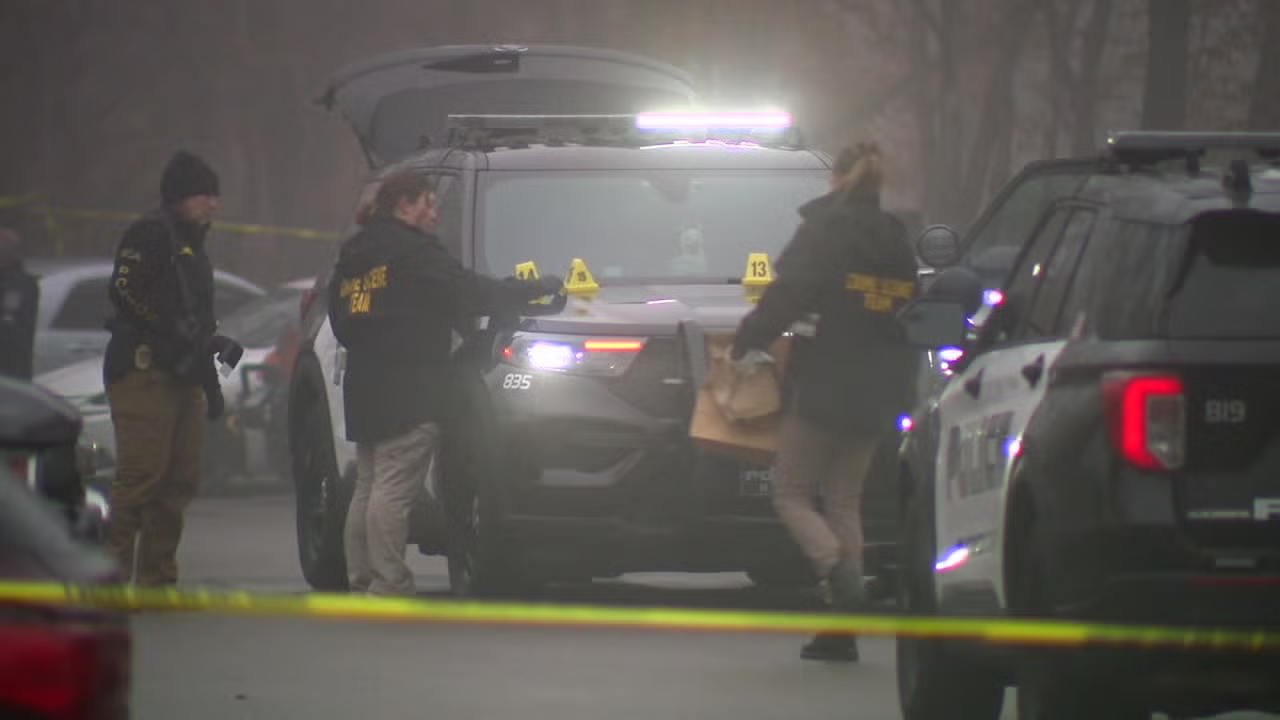

A dumpster is seen at a crime scene where the bodies of Tricia Nordman and Andrew Cataldi were found. (Scripps News Indianapolis)

Police discovered blood at the residence that DNA analysis determined belonged to Nordman. Evidence showed an attempt had been made to clean the blood; Hull had borrowed a carpet shampoo machine from a neighbor to clean the residence.

Pender said she purchased the shotgun and ammunition at a Walmart on the morning of Oct. 24, just hours before the murders. Hull was observed by the clerk obtaining ammunition that Pender paid for at the counter.

Pender recalled the events of that night, describing an argument between Hull and Cataldi that escalated while she walked away from the house. When she returned, she said she froze. She acknowledged she could have prevented the murders through different choices: not dating a drug dealer, not buying Hull a gun, running away or calling the police. She said she deserved to go to jail, but was shocked when the judge sentenced her to 110 years, 35 years more than Hull received, despite his admission that he was the shooter.

By 2007, facing the prospect of dying in prison or being released in her 70s, Pender became suicidal. She began a relationship with corrections officer Scott Spitler, who helped her escape in August 2008. She remained free for four months before she was captured in Chicago.

Pender spent five years and 12 days in solitary confinement, a period she described as “torture.” She detailed psychotic breaks, catatonic episodes and nights spent sobbing alone in her cell. Acting as her own attorney, she eventually sued the state of Indiana for failing to provide required mental health treatment. She won the case, and the state settled.

Her mother, Bonnie Prosser, testified about visiting Pender through glass during those five years, unable to hug her daughter. Multiple witnesses testified to Pender’s transformation during her incarceration. Dr. Kelsey Kauffman, who founded a college program at Indiana Women’s Prison, called Pender “one of the smartest students I’ve ever had” in 50 years of teaching. Kauffman described how Pender emerged from solitary confinement “shell-shocked” with PTSD but eventually became a leader in a public policy program studying collateral consequences of criminal actions. Other inmates referred to Pender as “the prison plant whisperer” for her skill with plants.

Tricia Nordman (R) and Andrew Cataldi (L) were shot to death in Indianapolis in Oct. 2000. (Scripps News Indianapolis)

Pender earned a bachelor’s degree from Oakland University while incarcerated and was accepted into a graduate program at Evergreen State University in Washington. She completed a culinary arts program and worked in legal aid, helping one woman reduce her sentence by 17 years.

Annie Kane, a Georgetown University student who made a documentary about Pender’s case as a part of the university’s Prison and Justice Initiative, testified about the impact Pender had on her life. Kane said Pender is the reason she wants to go to law school and become a public defender.

In 2017, Pender met Amanda Dixson during a weeklong catering event for a dog training program at the prison. The two women bonded over gardening, crocheting scarves for needy children and watching birds together. They married in prison in 2023. Dixson was released in 2021 with terminal ovarian cancer and died in 2024. Before her death, Dixson created a digital archive of her life for Pender to have after her release.

Pender’s father, Roland Pender, testified about the relationship’s impact on his daughter, saying the unconditional love Sarah received from Dixson changed her. He described how her relationship differed from her codependent relationship with Hull at age 21, saying she’s no longer codependent and has solid morals.

If released, Pender would live with her mother and aunt in Sun City, Arizona, in a three-bedroom home with a fenced backyard. Her father set aside money in an account in her name, supplemented by the settlement from her lawsuit against the state. Roland Pender and his wife are prepared to move to Arizona to support her. She has a provisional remote job offer with a construction company and plans to pursue her interest in sustainable agriculture. Her dream is to have a small farm and raise chickens.

Kauffman testified she would hire Pender to work on collateral consequences research and rated Pender’s potential for successful reentry in the “top 5 percent” of hundreds of incarcerated women she has worked with.

Richard Hull is seen in an image from Oct. 2000. (Scripps News Indianapolis)

Pender directed part of her statement to the families of Cataldi and Nordman, whose letters to the court were not read aloud. She apologized for the terrible loss they suffered and the role she played in it, saying she accepts their anger and understands it. She described Nordman as “sweet, kind and thoughtful” and recalled shopping with her and her mother shortly before the murders. She acknowledged that if Cataldi and Nordman were still alive, Nordman could be with her children and might have returned home, and Cataldi could have gone on to raise his own children.

“I can’t change the past. I’m asking for mercy to work towards a better future,” Pender said.

Pender’s defense team—attorneys Edward Delaney, Marc Howard and Martin Tankleff—asked Snyder to run her two murder sentences concurrently rather than consecutively, which would make her eligible for immediate release. The defense emphasized that no evidence proved Pender was the shooter and highlighted mitigating factors, including her sexual assault, her age at the time of the crime, her transformation in prison, and her five years in solitary confinement.

Notably, former Marion County Prosecutor Larry Sells—who called Pender “the female Charles Manson” when he charged her in 2000—wrote a letter supporting her resentencing. Marion County Chief Trial Deputy Daniel Cicchini represented the state at the hearing and argued the court should weigh all evidence in making its decision.

After hearing arguments from both sides, Judge James Snyder said he would take the matter under advisement and requested an updated progress report on Pender. He indicated he would issue a ruling at a later date.

As Pender was led from the courtroom, her mother watched from the gallery, having testified earlier about her dream of hugging her daughter every morning, afternoon and evening. Pender ended her statement with a promise and a plea, saying if freed, she will have her freedom and her family, and the court will never see her again unless they happen to be at Petrified Forest on a random day.

“I want to go home and make myself and the world a better place,” Pender said.

This story was generated with the assistance of AI using information gathered and verified by Emily Kean. Our editorial team verifies all reporting on all platforms for fairness and accuracy before publication.