Reinventing the heist film: Kelly Reichardt’s The Mastermind

Michael Mann used Jules Dassin’s gripping noir Rififi as a template when he directed Thief. Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Eleven borrowed its studied cool from the existential gaze of Alain Delon in Le Cercle Rouge. But one modern heist film has taken a different approach.

Kelly Reichardt’s The Mastermind – screening as part of Mubi’s American Outsider season of the director’s work – focuses more on the psychological than the procedural. It is less concerned with the felonious machinations of the theft and more with the mental toll taken on the desperadoes who commit the crime. Especially in the aftermath, when greed derails carefully laid plans.

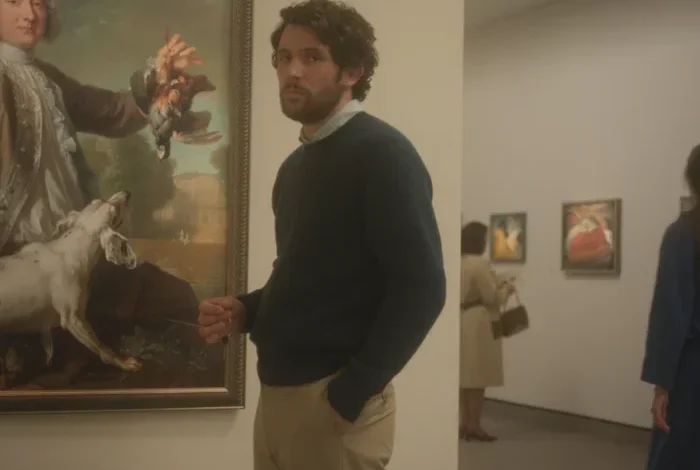

Reichardt’s leisurely crime caper follows failed art student and unemployed carpenter James Blaine Mooney, played by Josh O’Connor – so memorable in Luca Guadagnino’s Challengers and soon to be seen opposite Paul Mescal in The History of Sound – as he teams up with a typically ragtag gang of usual suspects who wander into a museum in broad daylight to steal four paintings by the American artist Arthur Dove.

Like Jonathan Glazer’s surreal Sexy Beast, Spike Lee’s table-turning Inside Man or Christopher Nolan’s heavily conceptual Inception, The Mastermind looks to subvert celluloid criminality, albeit in a gentler and less volatile fashion.

Reichardt’s previous works, such as the swampy anti-road-movie River of Grass, the period drama First Cow and the eco-thriller Night Moves – all part of the Mubi season – have exuded criminal tendencies. But this movie marks a change in genre for the filmmaker.

However, the style remains resolutely hers. This is an autumnal, understated heist film that unfolds in a stately and unobtrusive manner. Any sense of urgency is provided by Rob Mazurek’s frenetic freestyle jazz score.

The Mastermind is set in 1970s Massachusetts – inspired by the 1972 robbery of Worcester Art Museum in that state, where works by Picasso, Gauguin and Rembrandt were stolen – and is shot in the director’s trademark earthy tones with an exquisite eye for period detail.

Taking place against a tumultuous backdrop, in which the free love of the 60s has been replaced by cynicism and protests against the Vietnam War, The Mastermind, like many classic heist films, can be seen as a metaphor for ambition, identity and control. But more than that, it portrays the depths to which people who are struggling financially will sink to stay afloat.

In male-dominated films such as Mann’s Heat, Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs or Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing, the heist is a brazen display of arrogant machismo as the protagonists outsmart powerful, faceless corporations – or in the case of The Italian Job, the mafia – through meticulous planning.

Reichardt’s “mastermind” is the antithesis of these brazen displays. Mooney is just a struggling family man, much to the annoyance of his increasingly frustrated wife, played by Alana Haim (Licorice Pizza). There is no villainous undercurrent to his actions beyond making money, and he is often floundering to figure out his next move when things go awry.

Heist films find audiences rooting for underdogs, often out of their depth as they blur the line between genius and self-destruction. They may be on the wrong side of the law, but their nefarious actions make them far more enthralling to watch than those trying to stop them. As is their inexorable failure.

Get your 30-day free trial of Mubi.