Is Netflix Trying to Buy Warner Bros. or Kill It?

Why does Netflix want to buy Warner Bros.? In an era of mergers and megadeals, an age where content is king, a question like that might seem beyond naïve. As a newly, hugely bulked-up version of itself, Netflix will be ingesting a mountain of creative content that’s nearly mythological in its reach: everything from Clint Eastwood movies to the DC empire to “The Wizard of Oz” to the fabled HBO catalogue. Simply as an opportunity to expand what Netflix offers its streaming subscribers, the deal to buy Warner Bros. feels like some sort of ultimate bonanza. The sale itself still needs to get regulatory approval, and there’s actually a chance that that might not happen, but taken as a nervy commercial act of late capitalism, the Netflix/Warners deal needs no defense. The bottom line is clear.

But a larger question hovers in the air: If Warner Bros. Discovery is, at heart, a movie studio, what does it mean for a streaming service to buy a movie studio? The Amazon acquisition of MGM is not an instructive paradigm; when that happened, MGM was no longer a force in making movies — it was essentially a back catalogue (principally the James Bond films, and also the “Rocky” franchise), so there was an essential logic to that merger.

Warner Bros., however, remains a powerhouse of a movie studio. It’s one of the only companies that’s keeping movies as we’ve known them alive — this year alone, the high-profile release of such creatively daring and popular films as “Sinners,” “Weapons,” and “One Battle After Another,” along with popcorn films as potently commercial as “The Conjuring: Last Rites,” demonstrates that Warner Bros. is a company that’s helping to sustain not just the business of movies but the dream of movies: the ideal of larger-than-life entertainment experienced by audiences in movie theaters as a vital and essential popular art form. Some people think that movies are going the way of the horse-and-buggy. A company like Warner Bros. has been the tangible proof that they’re not.

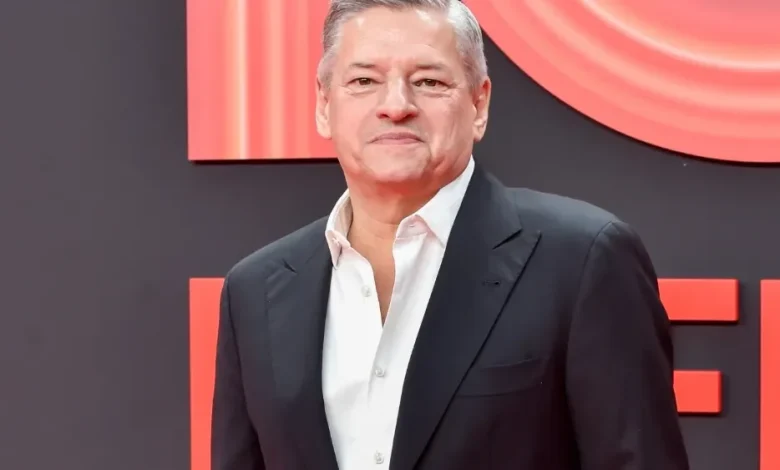

Ted Sarandos, the co-CEO of Netflix, has a different agenda. He has been unabashed about declaring that the era of movies seen in movie theaters is an antiquated concept. This is what he believes — which is fine. I think a more crucial point is that this is what he wants.

The Netflix business strategy isn’t simply about being the most successful streaming company. It’s about changing the way people watch movies; it’s about replacing what we used to call moviegoing with streaming. (You could still call it moviegoing, only now you’re just going into your living room.) It in no way demonizes Sarandos — he’d probably take it as a compliment — to say that there’s a world-domination aspect to the Netflix grand strategy. Sarandos’s vision is to have the entire planet wired, with everyone watching movies and shows at home. There’s a school of thought that sees this an advance, a step forward in civilization. “Remember the days when we used to have to go OUT to a movie theater? How funny! Now you can just pop up a movie — no trailers! — with the click of a remote.”

But ask anyone who loves going out to a movie and watching it on the big screen with a packed audience if the Netflix vision of things is really an advance. In certain ways it is…but in many ways it isn’t at all. Is watching a sports contest at home an “advance” over being there in an arena or stadium? Is ordering food at home an “advance” over going out to a restaurant? The Sarandos vision of the-future-is-now-and-you’re-doing-it-all-at-home is both a technological inevitability and, taken to its literal extreme, a cloistered form of cultural stuntedness.

But Sarandos is a shrewd tycoon. To make his agenda go down easier, he has created a kind of smokescreen around himself of “old-school movie love.” He describes himself as a cinephile. He has purchased and refurbished several fabled old movie theaters (the Egyptian in L.A., the Paris in New York) and uses them as a boutique billboard for his brand. “Look, Netflix still loves movies!”

And once in a while, a Netflix movie even gets to play in a movie theater — though not for long, and not in very many theaters. (You can usually count them on two hands.) One of my long-standing cynical japes is that because the movie theaters where Netflix programs its year-end awards-bait movies — from “The Irishman” to “Roma” to “The Power of the Dog” to this year’s “A House of Dynamite” — are just about all in New York and Los Angeles, where the majority of entertainment journalists live, the journalists have a skewed vision of how marginal the releases are. It’s playing at a theater near them, so the release seems viable. Sarandos made a special deal with Greta Gerwig, whose upcoming “Narnia” will play in IMAX theaters for two weeks before showing on Netflix. Yet even Gerwig had to push hard for that. You could feel the gritted teeth through which Sarandos agreed to the deal.

Once he owns Warner Bros., will Sarandos keep using the studio to make movies that enjoy powerful runs in theaters the way “Sinners” and “Weapons” and “One Battle After Another” did? In the statement he made to investors and media today, Sarandos said, “I’d say right now, you should count on everything that is planned on going to the theater through Warner Bros. will continue to go to the theaters through Warner Bros.” He added, “But our primary goal is to bring first-run movies to our members, because that’s what they’re looking for.” Not exactly a ringing declaration of loyalty to the religion of cinema.

And given Sarandos’s track record, there is no reason to believe that he will suddenly change his spots. A letter sent to Congress by a group of anonymous Hollywood producers, who voiced “grave concerns” about Netflix buying Warner Bros., stated, “They have no incentive to support theatrical exhibition, and they have every incentive to kill it.” If that happens, though, I have no doubt that Sarandos will be smart enough to do it gradually. Warner Bros. films will probably be released in a “normal” fashion…for a while. Maybe a year or two. But five years from now? There is good reason to believe that by then, a “Warner Bros. movie,” even a DC comic-book extravaganza, would be a streaming-only release, or maybe a two-weeks-in-theaters release. Do we know this to be true? No, but the indicators are somewhat overpowering. And given all that, why would Sarandos even need a movie studio to add to his streaming universe? If he really wants to make “Sinners,” he could make it today.

All of which brings me back to the question of why Netflix is buying Warner Bros. Yes, the new Netflix will be sitting on an awesome fresh mountain of content. But will the company continue the legacy of that content, collaborating with audacious filmmakers, giving them the resources to dream big, exhibiting their visions in the largest and grandest form possible? Or will all that gradually melt away? As much as one wants to give the new company a chance, it is hard, at this moment, to resist the suspicion that the ultimate reason Netflix is buying Warner Bros. is to eliminate the competition.